Anteromedial vs. posteromedial reconstructions—what are the indications and differences in sports injuries?

BY ELMAR HERBST, RYAN MARTIN, MIHO TANAKA AND ARMIN RUNER

-

Read the quick summary:

- Following an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, anteromedial structures in the knee may play an important role in supporting and stabilizing the joint.

- ACL and medial collateral ligament (MCL) re-rupture rates remain high, especially in high-level professional athletes; the authors believe that more detailed patient assessments involving preoperative imaging and physical examination may be required.

- The complexity of knee ligament biomechanics leads to difficulties when quantifying knee rotation, and improving measurement methods may lead to advances in treatment.

- Anteromedial reconstruction is likely to become a treatment option in cases of combined ACL-MCL injuries that involve anteromedial rotatory instability.

- The authors conclude that not enough is understood about patient outcomes of anteromedial reconstructions, unlike posteromedial reconstructions which have produced much clinical data.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

Among sports orthopedic surgeons, posteromedial rotatory instability (PMRI) has long been regarded as a frequent accompanying symptom of injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). However, a similar relationship between anteromedial rotatory instability (AMRI) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries has been acknowledged much less broadly.

In fact, only in recent years have research articles as well as discussions among medical professionals and clinical researchers begun to focus on the possibility that the anteromedial structures in the knee may play a much greater role than previously assumed in terms of supporting and stabilizing the joint in the aftermath of an ACL injury.

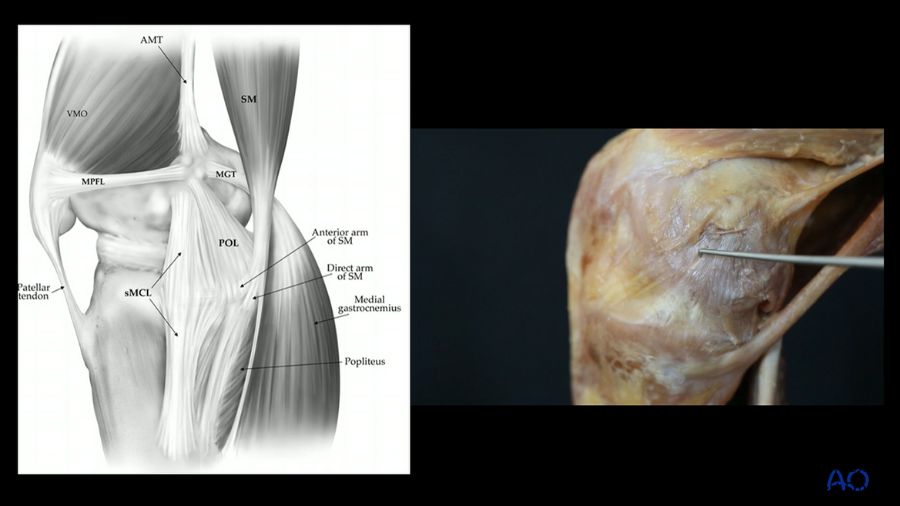

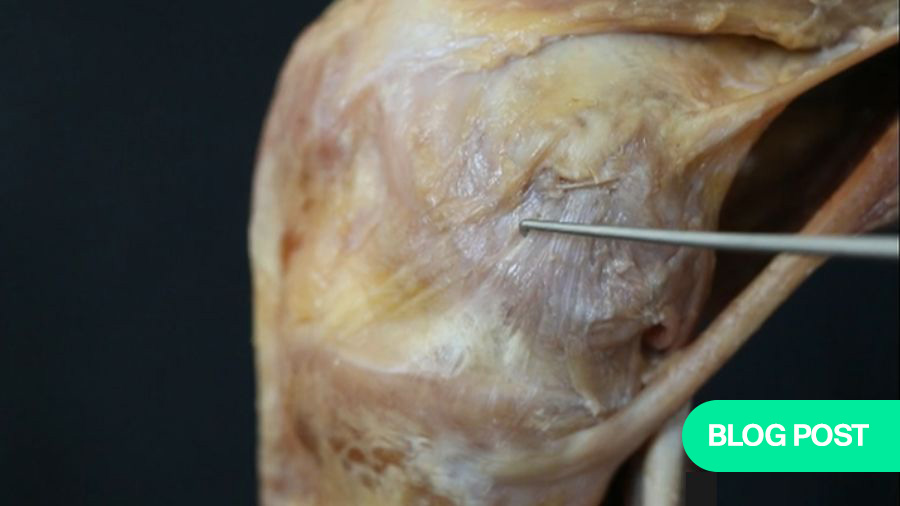

A closer look at the biomechanics of the knee seems to support this notion—the anteromedial retinaculum and the deep collateral ligament restrain anteromedial knee rotation. As the orientation of the ligament’s fibers directly mirrors that of the fibers of the ACL, it seems likely that the two structures work together in terms of restraining some of the loads.

If this is indeed the case, there is an important discussion to be had over whether controlling internal tibial rotation—which is regularly done during posteromedial reconstructions—is in fact the appropriate course of action. After all, most ACL injuries feature external tibial rotation. Bone edema and injury patterns on imaging also regularly suggest that external rotation of the tibia is likely involved. Thus, this injury pattern might not be addressed with a posteromedial reconstruction. In these cases, surgeons may have a closer look at anteromedial knee structures.

Combined ACL and MCL injuries

Unfortunately, it is not at all uncommon for professional athletes to experience injuries of the ligamentous structures around the knee during their careers. Chief among these is damage to the ACL. We also frequently observe injuries of the ACL and the medial collateral ligament (MCL) going hand in hand, especially in high-contact sports that involve a lot of cutting and pivoting motions. While an ACL injury requires surgery as a matter of course, that is not always the case with MCL damage. It is, therefore, very important for surgeons to be able to grade the severity of an injury in order to determine the appropriate course of treatment.

When making treatment decisions, a lot depends on the individual athlete, especially in the professional realm. For instance, at which point during the season has an injury occurred? Will there be sufficient time for post-surgery rehabilitation? How can we minimize the risks posed by an early return to play after a knee reconstruction?

Shifting the focus

Around ten years ago, sports orthopedic surgeons treating ACL injuries mainly concentrated on the anterolateral side of the knee. But while our patients are generally doing well, we are still not where we want to be, and our basic problem persists: re-rupture rates remain high, especially in high-level professional athletes. We simply have not managed yet to figure out sustainable solutions to this challenge. Research results confirm this: there is registry data that suggests that MCL injuries have a higher rate of failure than ACL reconstructions. Other research indicates that patients are not doing as well as we would expect them to.

In this context, it becomes clear that the current attention being given to anteromedial knee instability could be much more than a passing fad. We should acknowledge that we may have somewhat overlooked this approach in the past. In fact, we have to consider the possibility that we may previously have considered MCL injuries healed when this was not actually the case in terms of rotatory instability. Yes, recovery may have been sufficient enough to apply valgus load. But at the same time, we know now that rupturing the MCL fibers will significantly increase the strain on the ACL—in some studies by 130 percent, in others by as much as 180 percent.

This underlines how important it is to thoroughly examine every patient. Assessing whether the MCL is actually healed or not is more than just a valgus-based test. We also need a much more detailed look at the medial side of the knee. And hopefully, looking deeper into this topic will help us treat our patients better in the future. After all we, as well as our patients, only stand to benefit if we expand our diagnostic capabilities as much as we can by studying the relevant anatomy and biomechanics as extensively as possible to inform our treatment plans.

You only see what you know

For a long time, we simply did not know very much about anteromedial knee instability. And maybe that is part of the reason why we never thought to look more closely on our MRIs to actually figure out these injuries. In fact, there is an interesting study that looked at isolated ACL injuries only—and in over 65 percent of cases the researchers found a concomitant injury to the MCL as well as to the anteromedial part. It suggests that we just have not been looking closely enough at external rotation.

Having said that, quantifying knee rotation has always been a very difficult thing to do, no matter the side. We can measure many things, including varus and valgus deformities from the anterior and the posterior side. But quantifying rotation is very difficult. Now that anteromedial rotatory instability is coming under the spotlight, we really need to improve our measurement methods in order to advance our treatments, especially as it is so closely related to the assessment of outcomes.

Biomechanical considerations

Preoperative imaging can be a great help on the medial side. For instance, we commonly see postero-medial edemas that point to a subluxation. And in turn, this suggests that there is more going on than we may initially have thought. However, it should be emphasized that imaging cannot substitute a thorough physical examination. And these days, a Lachman test is not enough. Instead, we should provide information on what the Lachman is with internal as well as external tibial rotation. And that in itself should provide us with at least an inkling of what the image should be leading to when we examine the patient: you would expect an anteromedial-based injury to have more of a Lachman positive with external tibial rotation.

When it comes to interpreting MRI results, we have become comparatively good in terms of assessing the severity or the location of an injury. For instance, when we see distal injuries, we might take a closer look and consider surgery stronger than we would in cases of proximal or mid-substance-type injuries. We are not as good yet in terms of distinguishing between superficial and deep injuries. Having said that, unless it affects immediate treatment, management approaches will usually remain unchanged based only on superficial versus deep classification. The focus in cases of deep injuries should be on talking to the patient and educating them about possible outcomes, such as meniscus-related symptoms.

Understanding the injury mechanism

Always keep in mind that injury patterns can differ widely and that MCL injuries do not always follow the expected patterns. This is why talking to our patients to figure out exactly how their injury occurred should remain among the top items on our list of priorities. For instance, patients can present with an intact superficial MCL but an isolated deep MCL injury, and the only possibility for an isolated deep MCL injury to occur is in an isolated external tibial rotation. So, when you examine a football player with medial-sided pain and the Lachman test is positive, and then they tell you that they got hit on their toes and their tibia got externally rotated, you basically have the solution, at least from a diagnostical perspective.

We should also familiarize ourselves with the concept of strain: shorter ligaments will fail before longer ligaments. The superficial MCL is a longer ligament, so it can handle more strain. This is especially important when we consider constructs and how we propose to reconstruct them—we first have to understand why something failed.

New research, new approach?

For years, we have been reconstructing the superficial MCL and the posterior oblique ligament (POL) while largely avoiding the medial-sided valgus gapping. Put bluntly, we basically did not care too much about anteromedial rotatory instability—despite the fact that surgeons described it decades ago. Finally, this long-ignored knowledge is being reinforced.

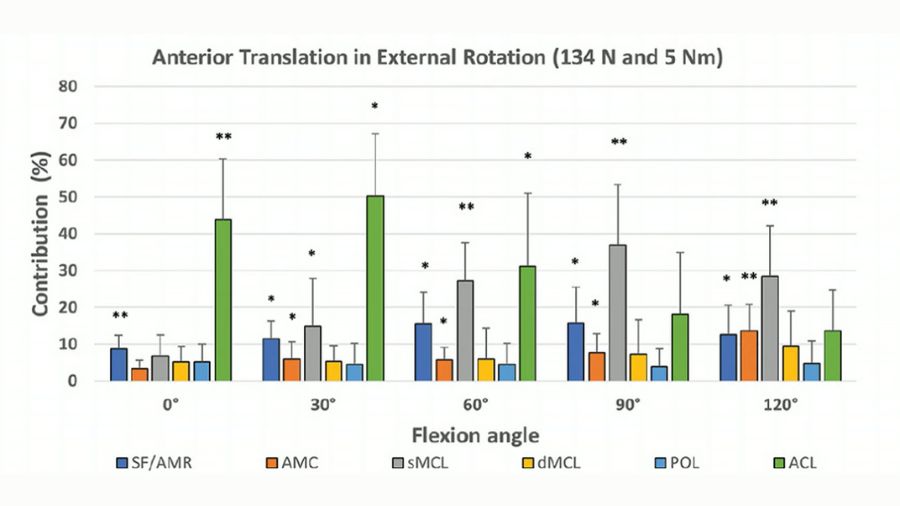

For instance, a recent study into knee ligament biomechanics looked at the contribution of each individual ligament on the medial side in response to anterior tibial translation in external rotations, or combined anteromedial rotation. The results clearly show that this type of rotation always involves some sort of combination of the ligaments. The green bars in Fig 1 indicate that during the first 60 degrees of flexion, the ACL provides most of the restraint. The gray bars represent the contribution of the superficial MCL, and it becomes clear that it takes over the main responsibility for restraint at some point above a 60-degree-rotation. The remaining ligaments, including the deep MCL and the anteromedial capsule, together contribute between 35 and 40 percent of the restraint in rotation of 60 degrees and more. It all points to the likelihood that knee ligament biomechanics are a lot more complex than we currently understand.

Proceed with caution

New research data is being publicized at a constant rate, and as surgeons, we must always be ready to adapt to it in order to optimize patient outcomes as much as possible.

The growing focus being placed on anteromedial reconstruction makes it more likely to become a treatment option in cases of combined ACL-MCL injuries that involve anteromedial rotatory instability in the future. In fact, we can already observe an uptick in the numbers of anteromedial reconstructions in ACL cases in some countries today.

Still, we should be careful to not get ahead of ourselves. Our ultimate goal, after all, is to ensure long-term knee stability and, for athletes, a safe return to their sport.

And while we do have a lot of clinical data for posteromedial reconstructions, we cannot yet say the same for anteromedial reconstructions, especially when it comes to cyclical data and long-term clinical evidence. We may be quite good in terms of anatomy and biomechanics, but we still do not know enough about the ultimate patient outcomes of anteromedial reconstructions. We also do not yet have solid criteria on which to base a decision for or against a reconstruction.

Clearly, it is good that we are looking ever more closely at the knee from all sides in terms of anatomy and biomechanics. But we should not jump on every train, and until we have more solid clinical evidence, we should always exercise caution.

Panel discussion

In this video, the authors discuss the topic of Anteromedial vs. posteromedial reconstructions.

About the authors:

Prof. Dr. med. univ. Elmar Herbst, PhD, is a trauma surgeon based at the University Hospital Münster. He specializes orthopaedic trauma, and sports injuries. Prof. Herbst has a strong academic and clinical background and is internationally recognized for his contributions to research in knee biomechanics, ligament reconstruction, and fractures around the knee. He has authored numerous peer-reviewed publications and serves as Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy (KSSTA), one of the leading journals in the field.

In addition to his clinical and academic work, Prof. Herbst is actively involved in AO Sports, teaching and mentoring medical students and residents, and fostering the next generation of orthopaedic and trauma surgeons. His dedication to advancing surgical techniques and improving patient care continues to impact both the academic and medical communities worldwide.

Dr. Ryan Martin, MD, FRCSC, is a distinguished orthopaedic surgeon based in Calgary, Alberta, specializing in orthopaedic trauma and arthroscopic knee surgery. He serves as an owner of Group23 Sports Medicine, where he leads a multidisciplinary team dedicated to providing comprehensive care for sports-related injuries.

In addition to his clinical practice, Dr. Martin is actively involved in academia as a Clinical Lecturer in Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Calgary. He is also a member of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health, contributing to research in orthopaedic surgery.

Dr. Martin serves as the team orthopaedic surgeon for the Calgary Stampeders Football Club and is currently an orthopaedic surgical consultant for the Calgary Wranglers and Calgary Flames.

His commitment to advancing orthopaedic care is further demonstrated through his role A Co-founder and Chief Medical Officer at Tactile Orthopaedics, a Calgary-based company specializing in creating realistic models that replicate knee and shoulder anatomy and the tactile feel of bones and soft tissue to train operating skills.

Dr Miho Tanaka is an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in sports medicine injuries. She serves as the Director of the Women's Sports Medicine Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and is an Associate Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School.

Dr Tanaka's primary research focus is on the biomechanics, imaging and anatomy of the patellofemoral joint. She additionally has interest in improving the understanding of treatment outcomes and injury prevention in female athletes.

Priv.-Doz. Mag. Dr. med. univ. Armin Runer is a consultant orthopaedic and trauma surgeon at the Department of Sports Orthopaedics, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Germany. He specializes in knee-related sports medicine, arthroscopic surgery, and osteotomies.

Dr. Runer served as a research fellow under Prof. Volker Musahl at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, where he gained extensive experience in biomechanics and clinical research.

His research focuses primarily on anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery, knee instability, and cartilage repair. Dr. Runer has contributed to over 90 scientific publications in these areas and has been recognized with several national and international awards, including the ISAKOS John J. Joyce Award for the best arthroscopy paper.

In addition to his clinical and research endeavours, Dr. Runer is an active member of several professional societies, including the German-speaking Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery Society (AGA), the German Knee Society (DKG), the European Society for Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA), and the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS).

You might also be interested in...

Precision over presumption

Dr John P Fulkerson examines why "patellofemoral syndrome" is not an adequate diagnosis.

AO Sports North America

Gold-standard AO education on the surgical treatment of sports injuries and other soft-tissue conditions around the joint.

Courses and webinars

AO Sports delivers high-quality, highly rated worldwide education focused on knee and shoulder injuries and deformities.