Precision over presumption—why "patellofemoral syndrome" is not an adequate diagnosis

BY DR JOHN P FULKERSON

The widely used term "patellofemoral syndrome" has become something of a catch-all diagnosis for anterior knee pain. However, it often oversimplifies the problem and delays accurate treatment. When it comes to better understanding anterior knee pain, the importance of precise diagnosis through thorough physical examination and advanced imaging technology cannot be emphasized enough.

One big problem in understanding anterior knee pain I have encountered time and again in my four decades as an orthopedic surgeon, is in the terminology. Because oftentimes, when no specific diagnosis is made to identify the cause of knee pain, patients will be told that they suffer from something called "patellofemoral syndrome". However, there really is no such syndrome per se. Nevertheless, the term has over time managed to establish itself as a kind of catch-all, used to lump together anyone with pain around the front of their knee.

From the perspective of the International Patellofemoral Study Group (IPSG), a high-level discussion forum of which I am a member, the broad consensus is that there is no such thing as a patellofemoral syndrome. Indeed, we have been actively working to discourage the use of that term.

The reason is that this diagnosis is almost like a stick-on label in that it is very difficult to remove from a patient once it has been applied—unless another practitioner takes a closer look and identifies, for instance, a specific structural problem. It can even be argued that in some cases, the terminology stands in the way of making a more specific diagnosis and of finding the actual cause of pain.

Rethinking knee pain diagnoses

For instance, a patient recently came into my practice with a diagnosis of patellofemoral syndrome. He was an athlete—a track coach, in fact—and he was very frustrated because it was six months on from his initial diagnosis, and still his pain persisted. A very careful physical examination revealed that his pain came from his patellofemoral joint—he had been doing a lot of heavy training, a lot of squats, and a lot of running. And what he in fact had, and we confirmed this with an MRI, was an articular lesion where the cartilage had softened and broken down, causing the pain.

Turns out, this was not a syndrome at all but rather a singular source of pain. This diagnosis was enormously helpful because it enabled us to look at the range of motion available to the patient without pain, allowing him to exercise in a way that did not aggravate the lesion further. He was also able to work on his core stability to help get his alignment better and to reduce pressure on the affected area.

Most importantly perhaps, the diagnosis enabled the patient to understand in his own mind what was going on. He was no longer in this nebulous realm. And I think we all appreciate that, with any health issue. We want to know exactly what it is.

In fact, I would argue that identification of the exact cause is where really good treatment for the patient begins. It comes down to careful clinical examination. Someone who is knowledgeable with the potential problems has to take a very close look and thoroughly examine every aspect of the support structure around the front of the knee, the mechanics of how the person walks, how that might be affecting their knee, and what kinds of specific sources of pain can come from mechanics that are off. They should also consider the activities a person has undertaken. The patient in my example had been doing squats and running, and he had arrived at a point of overuse and articular breakdown.

Looking at all these different aspects—sometimes in conjunction with imaging methods such as radionuclide scans or whatever else is necessary—will ultimately give us a very precise picture of what is wrong. For example, another patient of mine was also very frustrated because his pain could not be identified, and it was not getting any better. His diagnosis was patellofemoral syndrome, and the reality is that the physicians he has seen had simply accepted this and had stopped looking more closely.

However, the reality was that the patient had a very sensitive area in the support structure around his patella. More precisely, it was in the retinaculum—fibrous tissue that stabilizes the patella. We actually wrote a paper on this case. It was simply a matter of finding the specific cause of pain. When we did so, the patient told us that no doctor had previously put their finger on it. To confirm, I applied a little lidocaine, and the pain went away. Things like that are very satisfying, both to the patient and to myself as a physician. Because it relieves people of pain that they may have had for a really long time.

The risks of standardized treatments

Usually, when somebody is sent home with the idea that they have patellofemoral syndrome, it leads to a very standardized set of treatments. These are specific exercises familiar to physical therapists, such as stretching. And they can definitely help some people, regardless of the source of their pain. However, in other cases, time alone is all that is required, for instance to heal an overuse problem. And this is where it gets complicated, because there are different means of treating different conditions, and sometimes people are getting standardized physical therapy for something that is not going to respond to standardized treatment.

One problem with this is that many people will initially feel positively about being treated. But when they fail to get better, this feeling can turn on its head can and become an additional psychological burden. Another potential problem is that if someone receives a blanket treatment for a so-called syndrome, the treatment for a specific lesion can be missed.

My appeal to colleagues confronted with knee pain would therefore be to try really hard to see exactly where it is coming from. You can even try to enlist your patients' help in this by prompting them to put one finger on the source of their pain. It may take them a while, but oftentimes a patient can locate more or less precisely where their pain is coming from. Listen closely to your patients, because they can lead you to a specific diagnosis. And that saves a lot of wasted time, and a lot of generic treatment that may or may not be helpful. After all, the quicker you get to the main issue, the quicker your patient will get better.

Part of the problem of course is that the symptoms—unspecific pain around the front of the knee—are rather general. However, once the term patellofemoral syndrome is applied to a patient, it really takes away the thought process. Instead, they are told to do some generic exercises, and maybe they will be given anti-inflammatory medication. And these may help in a lot of cases. The point is, however, that it may not lead to the right treatment for each patient. A lot of patients will get better if you simply leave them alone for a couple of months. They might be spending a lot of time doing exercises that are not going to be helpful for their particular problem, but they will not get better. That is why we should really get down to the details from the very beginning and try to diagnose specifically as soon as possible.

3D imaging as a game changer

Among the most common causes for anterior knee pain is overuse, for instance in athletes. The best treatment in these cases of course is to avoid the activities that cause the overuse and switch to alternative exercises or physical therapy. The idea is to help strengthen the muscles without engaging in the activity that causes the pain, all of which can be included in a generic treatment program.

At the same time, in many cases, there is more to it than that. For instance, in recent years, we have been seeing increasing numbers of women, and particularly young women, who are more vulnerable to anterior knee pain. It is well-documented in the literature, and the reason is that young women are more prone to having some kind of dysplasia or malformation of the patellofemoral joint. This in turn can lead to overuse-related pain because something that is not formed quite correctly will not work quite correctly. As a result, these patients are more vulnerable to higher levels of activity. And once we understand that additional components such as these may be at work in some cases, it becomes easy to see that individually devised exercises may be more effective for some patients than a generic set.

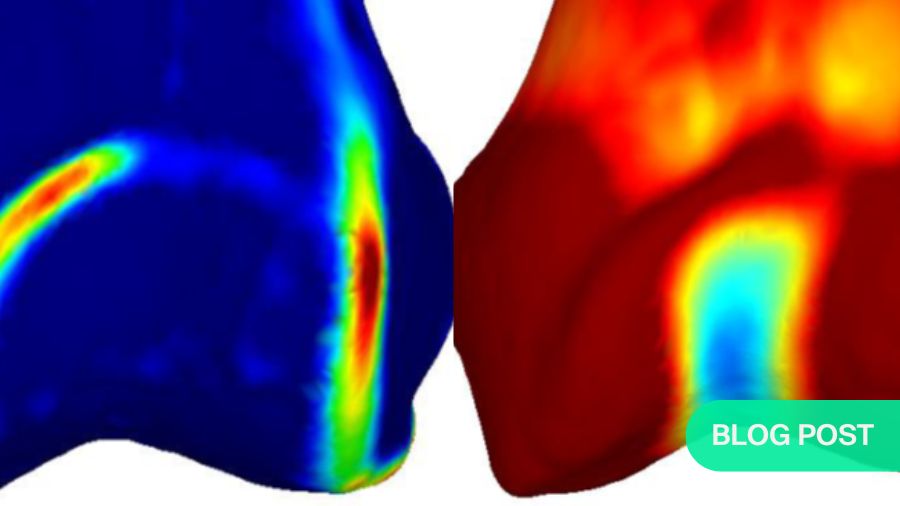

At the same time, we are now in the era of 3D imaging, which is really exciting. In fact, 3D imaging has become one of the first things I go to when somebody presents to me nowadays with a more obscure or a more resistant form of anterior knee pain and I suspect a structural malformation of the patella. With traditional two-dimensional imaging, it was very hard to pick up on the details of, for instance, trochlear dysplasia.

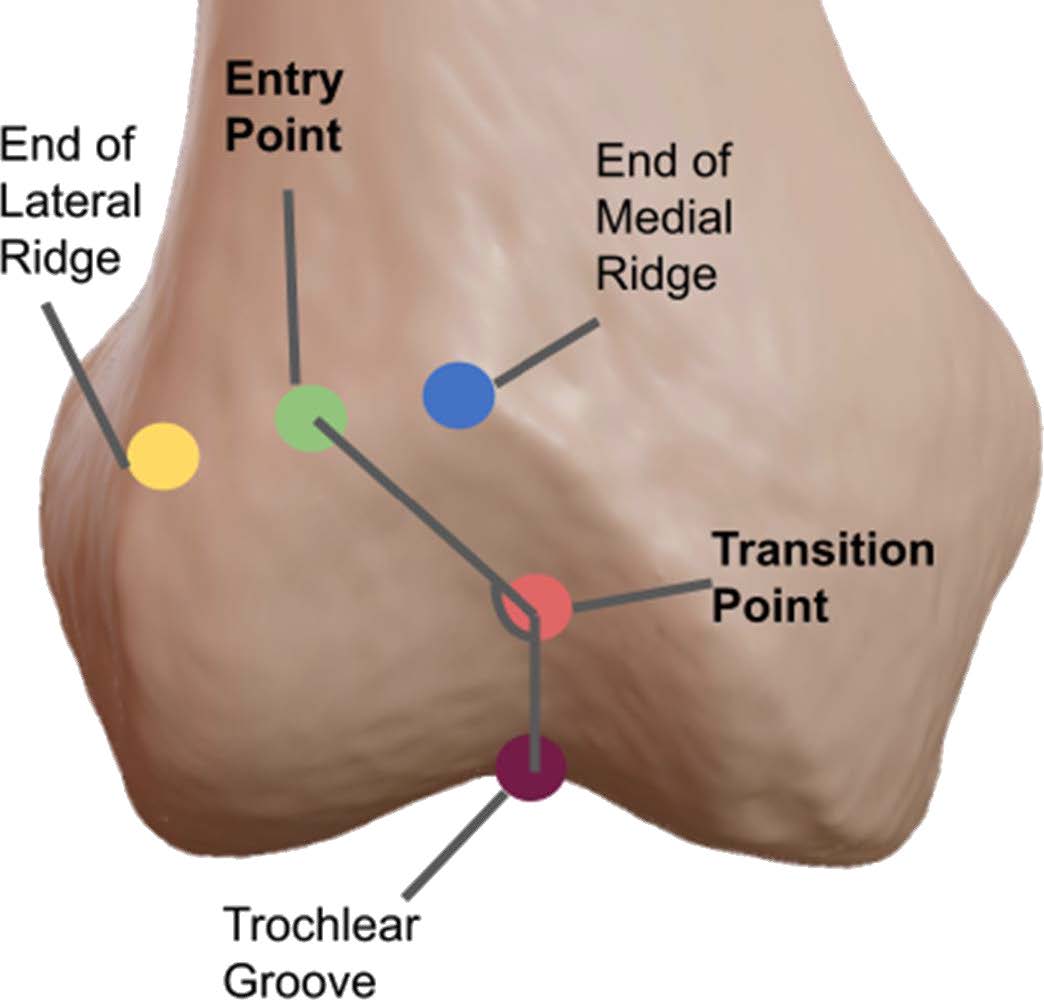

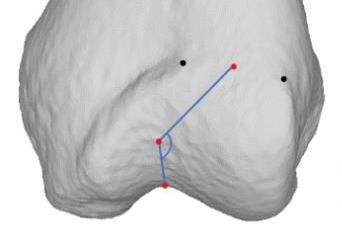

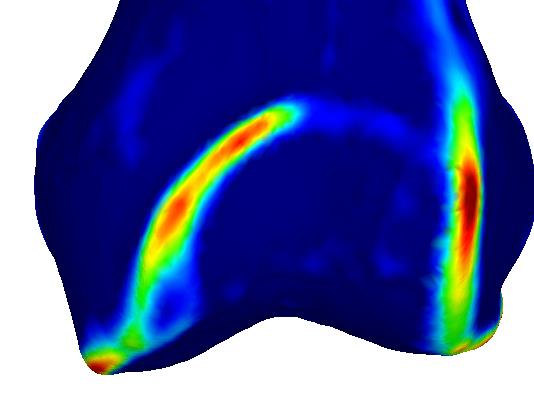

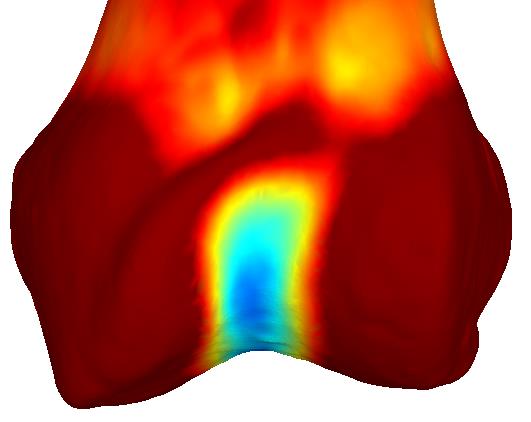

However, 3D imaging allows us to really understand the details of an abnormal dysplastic joint that causes, for instance, structural load changes, hyperloading, or a focal overload on the kneecap. Suddenly, we can see exactly what is going on. As a result, we can make qualified decisions on more specific treatment programs designed specifically for patients with, say, trochlear dysplasia that makes them more susceptible to developing pain around the front of the knee. The technology also enables us to generate three-dimensional imaging based on CAT scans, which are relatively inexpensive compared to MRI. It really has been a game changer.

We can better understand structural anomalies using 3D imaging. These 3D methods allow optimal treatment design by objectifying abnormal structure and therefore how best to advise and treat patients. Images used with permission, copyright Nancy Park (Figures 1 and 2) and Johannes Sieberer (3 and 4):

Balancing technology and clinical expertise

Of course, it is not universally applicable, and it certainly cannot be a substitute for professional diligence on the part of the physician. In fact, less than ten percent, and maybe even less than five per cent, of patients will require 3D imaging—we tend to use it only in more obscure cases. The real challenge awaits when a patient first comes in, and we really should be looking very hard at patients in terms of physical exam and basic imaging when available.

Indeed, the physical exam is the most important. Whenever a patient presents with anterior knee pain, I would urge colleagues to first ask them what exactly they have been doing—what activities they have been exposing their knees to—and then to perform a really thorough exam. Instead of just moving the knee around to see if there is a little crunch or a little swelling or something, you should really take your time. Devote ten or fifteen minutes to looking at the knee through the full range of motion. Look at every aspect of the contact of the patella. Where does it hurt in that range of motion? Where does it hurt around the patella? Take a moment to consider the quadricep tendon. Rarely will you ever see somebody come in with a quadricep tendonitis, but it is right around the front of the knee where the quad muscle goes into the patella, so we should keep it in mind.

Imagine how great it would be if somebody went to their trainer or their physical therapist or their family doctor, and they simply put a finger on it and asked whether it hurt. And that is exactly what I think is missing too often—we just do not see a lot of people with those kinds of very specific diagnoses. My plea would therefore be to take every case of anterior knee pain seriously. Because it is taking a lot of people out of their activities: parents cannot play with their kids in the backyard because they cannot run around and kick a ball.

Moreover, arriving at a final diagnosis as quickly as possible by way of a very thorough physical exam and good, well-controlled basic imaging would lead to a lot more people being spared a lot of unnecessary exercise. Some people with overuse simply need to rest. The number of people who come in to see me with overuse-related knee pain who have been put through exercise after exercise that actually fire up their knee and make it worse instead of better is genuinely surprising.

Every time that a clinician identifies something specific such as overuse, it not only significantly reduces the time until the patient's recovery—it also saves them from having to consult specialists later on to try to track down the source. And when someone really fails to get better in spite of having had a good diagnosis, they can be referred to somebody with a lot of experience with the specific diagnosis and who can apply 3D imaging or whatever else is required to refine the diagnosis further.

Fostering the thought process

I mentioned earlier how in some cases you can enlist the help of your patient to track down the source of the pain. Bill Post, the chairman of the IPSG, and myself conducted a study for which we gave patients a picture of a knee from the front and the side and asked them to mark with a pencil where they thought their own knee hurt. Without seeing these papers, we then examined the patients to establish where their pain was coming from. In 70 percent of the cases, where the patient said their pain was coming from correlated with where we concluded it was coming from based on our physical exam. What this shows is that most patients can really lead us to the source of the pain if we let them.

Essentially, it is an exercise in raising patients' awareness of their own bodies. Some people never even think of properly listening to what their body tells them. As healthcare providers, we should really empower our patients to go through a thoughtful process with ourselves as guides. After all, we know the structure, we know the anatomy, we know all the stuff that is in there. The challenge is to establish some kind of connection and to encourage them to tell us where the pain is really coming from. And that is a lot different than simply saying you have a syndrome, which is simply the end of the thought process.

And that is why, if things were up to me, I would ban the term patellofemoral syndrome completely, because it is nothing but an easy way out. Instead, we should simply call it what it is—anterior knee pain—and take it as a prompt to initiate a very careful diagnostic process. Right now, people do not particularly like hearing that they have anterior knee pain because they already know that. In truth however, saying that they have patellofemoral syndrome is really the same—it simply sounds a little more scientific.

About the author:

Dr John P Fulkerson is a Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Yale specializing in patella instability surgery and 3-D innovative research. He published Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint and is founder of both the International Patellofemoral Study Group and The Patellofemoral Foundation (www.patellofemoral.org).

In the past, he has been Head team physician for the NHL Hartford Whalers and Hartford Wolfpack as well as a team physician for US Olympic Men's Ice Hockey and Trinity College (Hartford). He has published extensively in the scientific literature regarding the patellofemoral joint, authored many chapters, monographs and one book on the topic.

He is probably best known for orthopedic surgical innovation-first describing several common surgical procedures: anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle, medial quadriceps tendon-femoral ligament reconstruction, and first publication in the world's literature on bone-free quadriceps tendon reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (1998), an ACL graft alternative that is increasingly popular today.

Fulkerson has lectured extensively around the world and received many awards including the San Francisco Bay Area Lifetime Achievement Award, The Patellofemoral Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, the AOSSM Sports Medicine Hall of Fame 2023, US News and World Report Top Doctors, the Wisdom House Community Service Award (with his wife Lynn), University of Connecticut Sports Medicine Fellow Educator of the Year 2020, and Connecticut Orthopedist of the Year 2016.

You might also be interested in:

AO NA Sports

Gold-standard AO education on the surgical treatment of sports injuries and other soft-tissue conditions around the joint.

AO NA Sports courses and webinars

AO Sports delivers high-quality, highly rated worldwide education focused on knee and shoulder injuries and deformities.

AO Surgery Reference

AO’s powerful all-in-one online reference supporting you from patient assessment to aftercare.