Reconstructing a shattered knee: A case study in complex intra-articular fracture management

BY DR KASHYAP ARDESHNA

When a 58-year-old active farmer suffered a catastrophic knee injury, an orthopedic surgeon in Gujarat, India, undertook a rare and challenging surgical reconstruction. Here, Dr. Kashyap Ardeshna provides a first-hand account of the surgical approach, decision-making, postoperative strategy, and long-term outcome of a severe multi-fragmentary fracture of the knee joint.

Dr Kashyap Ardeshna's case presented in this Guest Blog was the winner of the myAO Case Competition 2025.

-

Read the quick summary:

- A patient presented with a highly comminuted knee fracture that involved several individual fragments within the joint

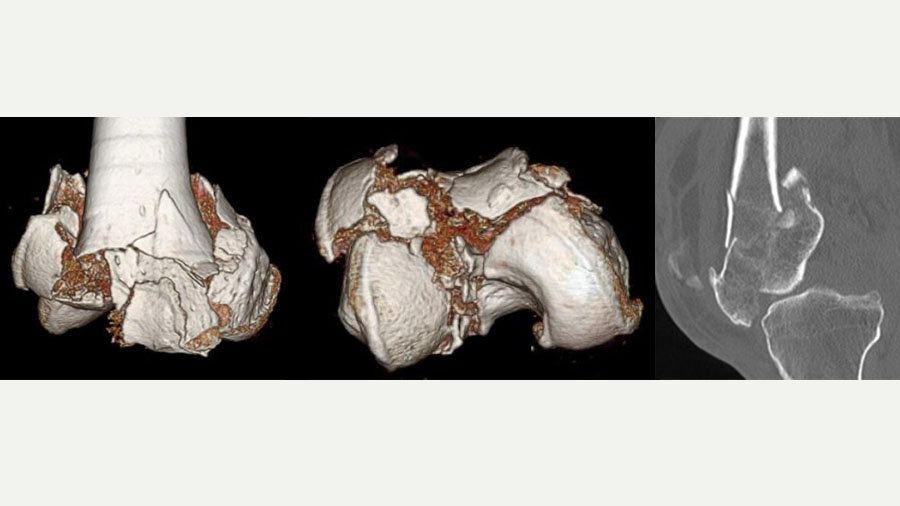

- X-rays provided an initial overview and a CT scan delivered the critical 3D visualization of the fracture pattern, helping enormously in preoperative planning

- The articular surface was reconstructed using temporary fixation with Kirschner wires (K-wires); autologous bone was packed into the cavity to provide structural support and facilitate fracture healing

- Permanent fixation was achieved using two plates and multiple screws, with some improvisation

- After staged physiotherapy, the patient is ambulatory without support, and able to return to work

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

I have been practicing orthopedic surgery for over 25 years in Gujarat, India, with a primary focus on general trauma cases. As orthopedic surgeons we often say, “every fracture is a different fracture,” but this particular case stood out due to its severity and the resilience required both by the surgery team and the patient.

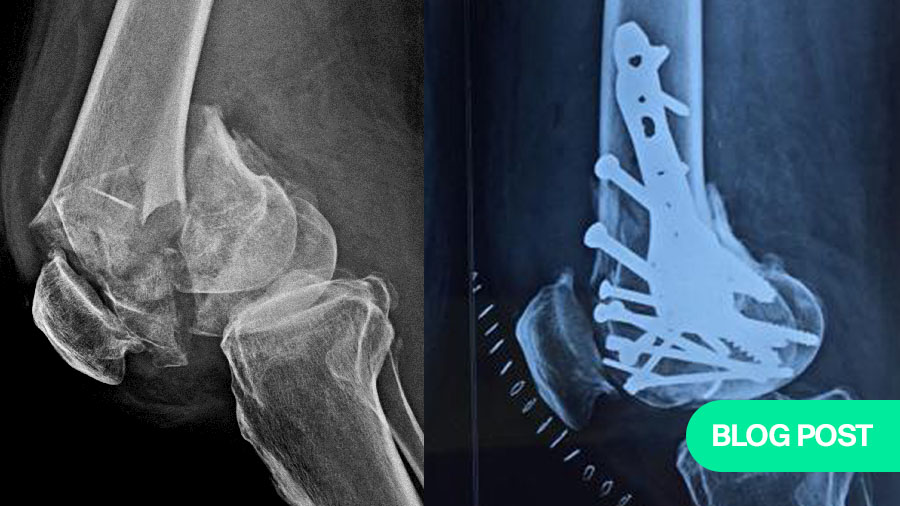

A 58-year-old farmer, the patient had always been physically active despite some age-related degenerative changes in his knees. His injury occurred from a fall in which he landed directly on his knee, resulting in a highly comminuted fracture. On initial inspection, the fracture resembled a shattered stone, with seven to eight individual fragments within the knee joint. These fragments included articular surfaces critical for knee function, making the restoration of joint congruity both urgent and exceptionally challenging.

What made this case significant was not only the extent of the injury but also the context: this was a man who relied almost entirely on his ability to perform physical labor. A poor outcome could have meant permanent disability, severely affecting not just his quality of life but jeopardizing his entire livelihood.

The complexity of the injury required a structured, multi-step approach, starting with comprehensive imaging. While X-rays provided an initial overview, it was the CT scan that delivered the critical 3D visualization of the fracture pattern. This enabled precise identification of each fragment and helped enormously in preoperative planning.

Such advanced imaging is essential for joint injuries where the accuracy of reduction dictates functional outcome. It allowed me to mentally reconstruct the knee and consider the tools and implants I would need. A detailed plan was then developed with contingencies in place—Plan B, and Plan C etc—including alternatives for fixation devices that might not conform to standard knee fracture patterns.

Equally important was patient counseling. I met with the patient and his family to explain the gravity of the injury, the surgical complexity, and all the possible outcomes, including the chance he might never regain full function. He was made aware of the possible need for job modifications and restrictions in his daily activities. After thorough discussions and obtaining informed consent, we proceeded with surgery.

The operation: piecing together a broken puzzle

Given the patient’s age and the extent of the fracture, a full pre-anesthetic workup was completed, and he was cleared for surgery. I assembled a surgical team of two orthopedic surgeons and four support staff, because I favored a team-based approach due to the anticipated technical challenges.

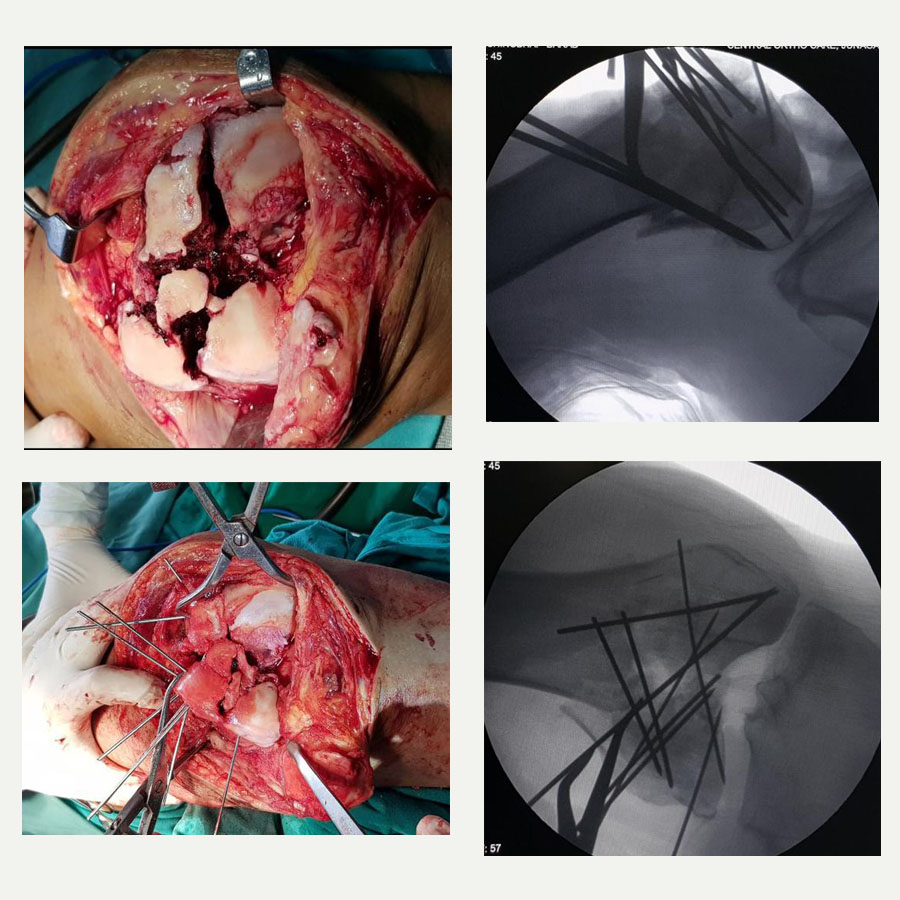

The joint was exposed via an open procedure similar to that used in total knee arthroplasty, allowing us full visibility. What we encountered were multiple fragments, many of which were too small to individually identify without proper sequencing – much like solving a jigsaw puzzle. The first step was to reconstruct the articular surface using temporary fixation with Kirschner wires (K-wires). Fragment by fragment, we identified and aligned them to reform the joint’s surface. Once reconstructed, this block of bone was then aligned with the diaphysis of the tibia.

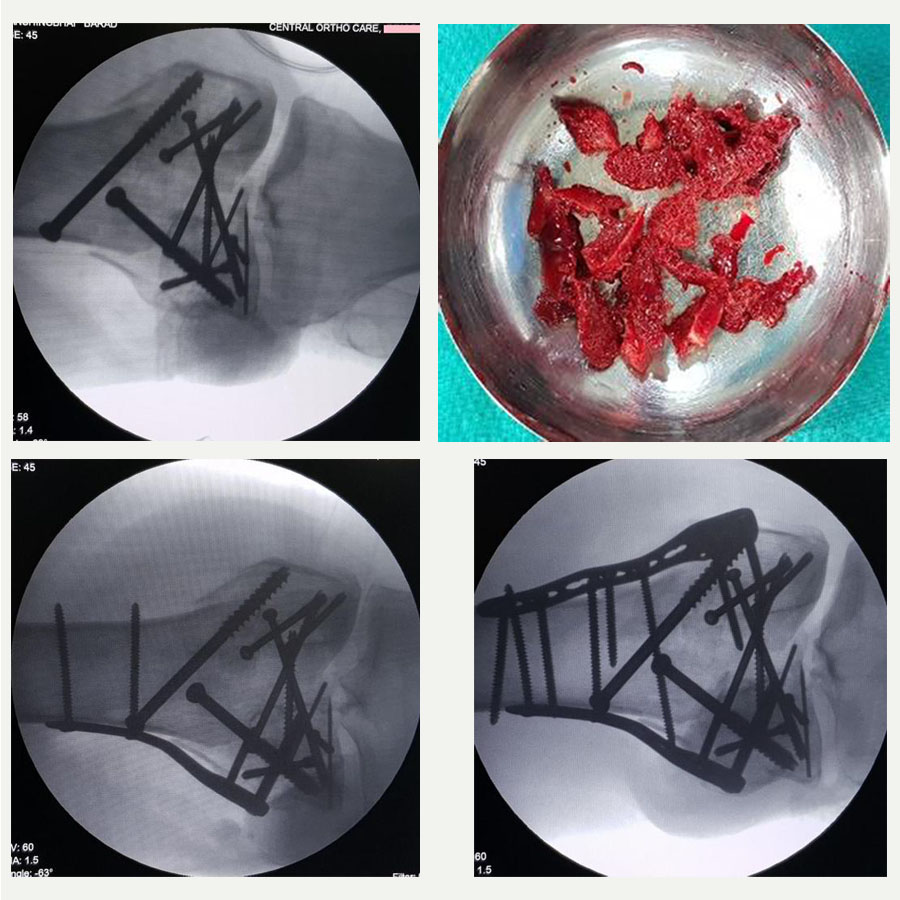

One of the critical intraoperative challenges was the presence of a void within the area, a consequence of both osteoporosis and the impact of the fall. Anticipating this, we had prepared to perform bone grafting. Autologous bone was harvested from the patient’s iliac crest and packed into the cavity to provide structural support and facilitate fracture healing.

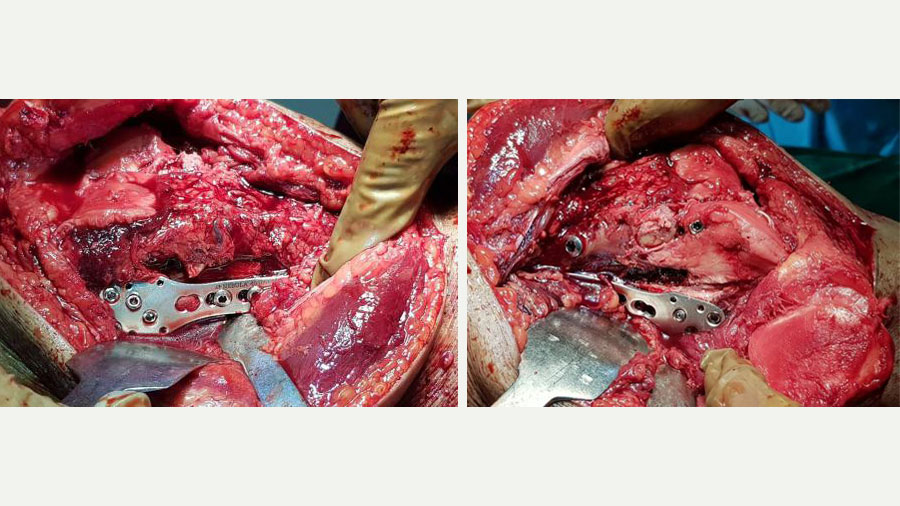

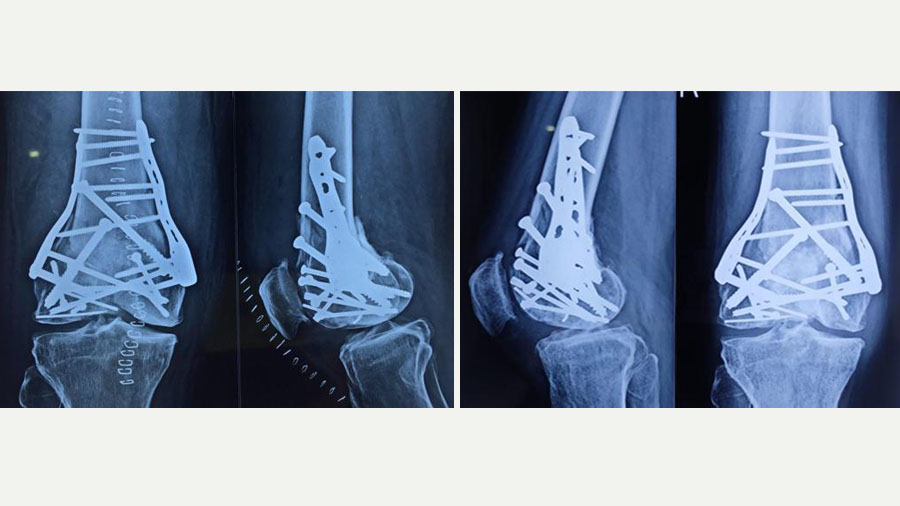

Permanent fixation was then achieved using two plates and multiple screws. Due to the unavailability of a dedicated plate for this particular fracture configuration, we used a shoulder locking plate, which fitted anatomically well for medial and lateral support. This unorthodox but carefully considered decision underscores the importance of improvisation when conventional tools fall short.

Some people may also ask why we did not perform a knee replacement from the outset, given the extent of damage. The answer lies in the nature of the fracture. In a primary knee replacement, only the articular surface is replaced, resting on structurally sound bone. In this case, the bone itself was destroyed.

Had we chosen replacement initially, we would have needed a tumor prosthesis – a bulky, costly, and complex option with a relatively short lifespan and considerable functional restrictions. By reconstructing the native bone, we preserved the possibility of a more standard primary knee replacement in the future, should it become necessary.

Postoperative management: protecting the repair and achieving function

The immediate postoperative priority was to prevent joint stiffness while protecting the structural repair. Fortunately, the wound healed well without infection – a major concern in prolonged surgeries involving internal fixation.

We initiated active and assisted active knee motion exercises from the second postoperative day to preserve mobility and prevent stiffness. However, due to the fragility of the fixation and the extensive reconstruction, we delayed weight-bearing for three months. During this time, the patient performed in-bed exercises for joint mobilization.

It wasn’t until the three-month mark that we introduced partial weight-bearing using a walker. Progress was closely monitored both clinically and radiologically. By four and a half months, the patient was walking independently with a cane. At six months post-op, he had resumed driving his motorbike and was able to perform 60-70% of his usual agricultural work.

Now, two years post-injury, the patient is ambulatory without support, actively working on his farm, and satisfied with his recovery. His range of motion is functional, though we have advised him to avoid squatting or sitting cross-legged – common postures in rural India – to minimize joint stress and delay further degeneration.

We continue to monitor him periodically, and so far, there has been no need for further surgical intervention.

The value of bone grafting in comminuted fractures

This case reinforced several important principles that continue to shape my surgical practice. Foremost among them is the importance of maintaining hope. At the outset, the fracture appeared irreparable – a scenario that could easily discourage both patient and surgeon. However, through meticulous planning, a structured surgical strategy, and unwavering cooperation from the patient, we achieved an outcome that surpassed initial expectations. Holding onto a realistic yet optimistic mindset proved essential throughout the process.

Equally critical was the role of preoperative counseling. Patient education is not just about consent; it's about partnership. Ensuring that the patient and their family fully understood the severity of the injury, the complexities of the surgical plan, and the long-term commitment to rehabilitation was instrumental in achieving a successful recovery. This transparency helped build trust and prepared them for the journey ahead.

Another key takeaway was the need to be prepared for the unexpected. Complex fractures rarely conform to standard approaches. In this case, we ensured that a broad selection of implants was available, including off-label devices such as shoulder plates, which ultimately provided the most suitable fixation. Having multiple contingency plans in place offered intraoperative flexibility and bolstered decision-making confidence.

Teamwork played a pivotal role throughout the surgery. Collaborating with another experienced orthopedic surgeon enhanced the quality of intraoperative assessments and allowed us to manage the procedure more efficiently. In surgeries of this scale and complexity, a single-surgeon approach would be suboptimal; collective expertise elevates the standard of care.

Postoperative management also revealed the delicate balance between initiating early joint motion to avoid stiffness and delaying weight-bearing to protect the fixation. We began movement exercises from the second postoperative day while postponing any load bearing for three months, ensuring that the structural integrity of the reconstruction was preserved.

Clear patient communication around this phased approach was crucial to compliance and long-term success. The patient’s discipline and cooperation during the rehabilitation phase were equally important. We repeatedly emphasized the need for strict adherence to postoperative guidelines, and he complied diligently.

Lastly, this case reaffirmed the value of bone grafting in managing metaphyseal defects in osteoporotic, comminuted fractures. The autologous bone harvested from the iliac crest integrated well and provided the necessary scaffold for bone healing. Proactively incorporating grafting into our surgical plan significantly contributed to the outcome and is a strategy I would readily employ again in similar cases.

Together, these lessons highlight the interplay between technical preparation, adaptive thinking, collaborative effort, and patient engagement – all of which are essential in managing complex orthopedic trauma.

To other surgeons facing similar cases, I would say this: invest as much effort in planning and patient counseling as in the technical aspects of surgery. Keep backup options ready, involve a team, use the resources at hand wisely—and always, always give your patient hope.

About the author:

Dr Kashyap Ardeshna has 25 years’ experience as an orthopedic surgeon in Junagadh, Gujarat, India. His main areas of interest are complex periarticular fractures, revision trauma surgeries and knee surgery—including joint preservation, joint replacement and arthroscopic surgeries.

He is AO Trauma faculty to many AO Trauma courses, and invited faculty to many state and national orthopaedic trauma conferences.

You might also be interested in...

AO Surgery Reference

A resource for the management of fractures, based on current clinical principles, practices, and available evidence.

myAO

Community access to relevant, trusted sources of knowledge, moderated case discussions, and expertise across AO specialties.

AO Trauma Fellowships

Opportunities for young surgeons to learn from leading AO Trauma experts in carefully selected and renowned centers.

AO Course Finder

Find accredited and high quality educational activities from AO across different pathologies. Explore your next learning activity.