Proximal femoral fractures—acute management and indications for hip replacement

WITH CHRISTOPH SOMMER, PETER BATES, XAVIER GRIFFIN, JAMES WADDELL

In a recent AO webinar on proximal femoral shaft or neck fractures, Christoph Sommer, Peter Bates, Xavier Griffin, and James Waddell discussed these common injuries. In younger patients, they tend to result from high-impact events such as falls from heights or motor-vehicle accidents; for older ones, many of whom are osteoporotic, even minor falls can result in fractures. And while the number of younger people with these fractures is fairly constant, the number of older patients, especially women, is growing as the baby-boom generation move into old age.

Below each of the four authors considers typical cases with possible treatment and complications. AO members can watch the full webinar in the AO Video Hub.

Fixation of femoral neck fractures using a new implant—tips and tricks

By Christoph Sommer

As Sommer works in Chur, a popular Swiss ski area, he often deals with snow-sport injuries. Sommer worked with the AO Technical Commission (AOTC (AOTK in German)) to develop the Femoral Neck System (FNS) implant, which was released in 2017. In conjunction with minimally invasive techniques to implant the FNS, his reductions of displaced femoral neck fractures drew praise from his fellow presenters. As open reductions significantly increase the risk of deep bone infection, Sommer manages 95% of femoral neck injuries with closed reductions. His post-operative images indicate excellent results.

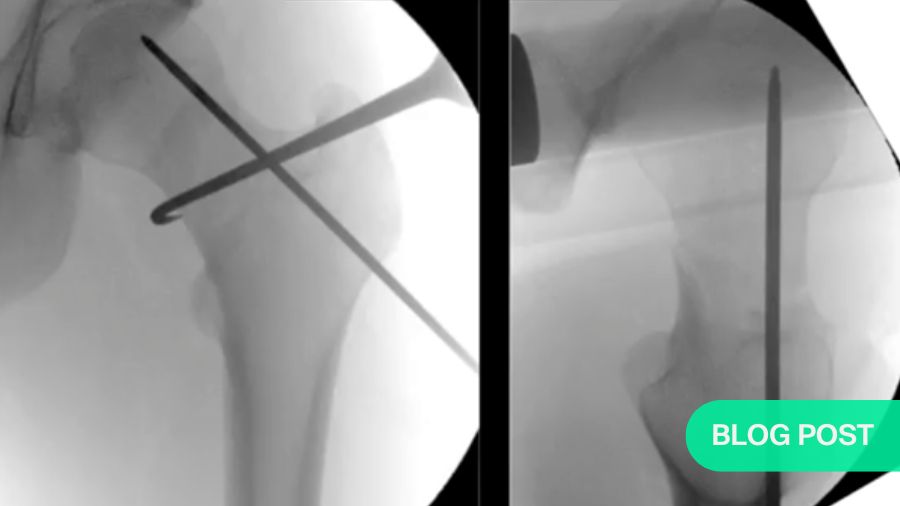

Sommer’s preferred strategy is to apply traction to the affected leg, then turn it inward until the two parts of the femoral neck line up. With the bones roughly aligned, he then uses minimally invasive techniques to remove any bone fragments. Then, relying on vertical and horizontal fluoroscopic views, he can fine-tune the alignment before completing the fixation. One innovative trick he uses is to insert a hook into the fracture site to pull the separated ends into position. He then uses a Femoral Neck System (FNS) implant to fix the fracture.

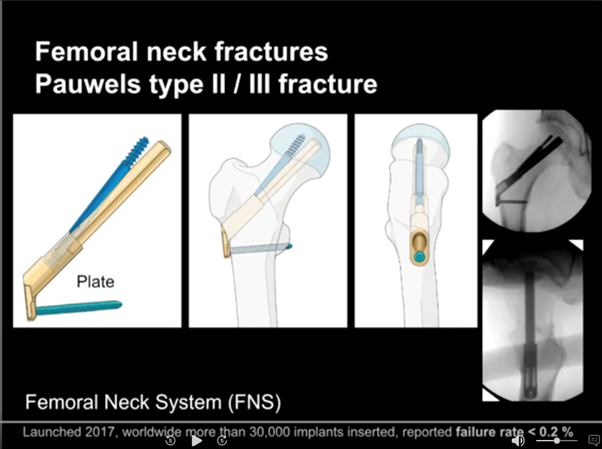

The FNS (shown below) has only four parts: a plate, a bolt, an anti-rotation screw and a locking head screw. K-wires can be used to hold the bone fragments temporarily in place. The result is highly-reliable fixation (<.2% failure rate based on 30000 implantations) that requires a minimal incision, leaving a small surgical footprint with no protruding parts, centric positioning of the neck screw or bolt and solid resistance against rotation. Additionally, it is compact enough for use in Asian patients, who often have rather small femoral necks.

One particularly useful feature of the FNS is that, in addition to providing extremely stable fixation, it allows the surgeon to limit the amount of dynamization, i.e., shortening, that occurs in the fracture site. As femoral necks commonly lose around 15mm of their length while healing (resulting in a 10cm loss of leg length), the FNS’s impaction-limiting function offers a considerable long-term advantage over previous implants.

At the time of his lecture, Sommer noted that no optimal impaction limit had yet been determined. However, he chose 7mm for the example he showed. He also explained and illustrated the process as part of his lecture.

As for the latitude available for malreduction, while Sommer gave clear instructions on how to ensure very close anatomic reductions, he also said a malreduction of up to 20 degrees would still heal, but might later lead to functional problems. If a slight malreduction is necessary, he recommended that a slightly valgus angle was preferable to a varus one. However, he recommended eliminating any distraction.

And while he almost always uses closed reductions, there are also cases where Sommer concedes that an open reduction is necessary. For example, in a case where the femoral head is completely disconnected from the distal fragment and the capsule is clearly ruptured, there would be no choice.

Also, as of 2022, after almost five years in distribution and 30000 implantations, the FNS had an excellent record, rarely requiring removal. One exception would be where a later fracture required a total hip replacement.

Ipsilateral femoral neck and shaft fractures

By Peter Bates

Bates begins by observing that, as most of the studies in femoral neck and shaft fractures are relatively small (n<100), there is virtually no consensus even on how common they are. While he mentions a 1997 meta-analysis in which the researcher suggested that as many as 9% of femoral shaft fractures have concurrent neck fractures (Alho, 1997)1, based on personal observation, he suggests that femoral neck fractures may be much closer to Marins et al.’s 2021 finding of 1.1% (Marins et al., 2021).2

Regardless of their incidence, when the two fractures occur together, Bates recommends not trying to manage both with a single reduction or fixation solution. Instead, he suggests treating them as completely separate injuries. This strategy means, for example, that the fixed femoral shaft can be manipulated as shown above by Sommer to achieve a more accurate reduction of the neck fracture. In cases where the femoral neck fracture is undisplaced, that can be temporarily stabilized, e.g., with k-wires, the shaft reduced, and the definitive neck fixation managed.

Always check for a neck fracture

One important point to remember is that, in the 1997 meta-analysis cited above, Alho also estimated that as many as 30% of femoral neck fractures go unnoticed.3 In this case, given the advances in imaging technology since then, Bates suggests that the current number is much closer to Gupta et al.’s 2022 finding that 6% of such fractures were missed.4 He also notes that, while concurrent femoral neck fractures rarely accompany shaft fractures, those that do are often undisplaced, which makes them very easy to miss.

When that happens, the surgery appears to go well, but the patient later complains of pain. Only with a CT scan does the undisplaced fracture become visible. As this necessitates a second surgery, it is cost-effective simply to take a few seconds to test every femoral shaft fracture for a broken neck. Therefore, in addition to carefully examining preoperative CT images, after fixing the shaft, Bates recommends loosening the traction and rotating the leg slightly left and right to expose any neck fracture.

The one advantage of a virtually-invisible undisplaced fracture is that no reduction is necessary and an anatomic fixation is very easy to achieve. Bates also notes that, in dual shaft/neck fractures where the shaft fracture is relatively simple, femoral neck fractures tend to be easy to spot, but much more complex to reduce and fix. In these cases, the majority are basicervical or intracapsular and rotationally unstable, and may be vertically oriented, i.e., to have high Pauwels angles. In all cases of concurrent femoral neck and shaft fractures, but especially those involving complex neck fractures, Bates cautions his listeners that using one implant to fix the whole fracture, particularly in the face of a displaced femoral neck can be awkward, because it's a less forgiving implant. (28:20)

Complications

For shaft fractures, non-union is the most common complication. In the neck, avascular necrosis (AVN) is most common, while non-union or cutout (due to poor placement of implants) are both rare. As no fixation solutions have yet been determined to offer superior results, Bates advises surgeons to work with systems they are comfortable using.

Damage control measures often become definitive

For polytraumatic patients, Bates cautions against damage-control measures beyond the bare minimum, as temporary plating often becomes permanent. And with a complex surgery that is outside the surgeon’s specialization, Bates’ solution is very simple:

Wash out the wound, close it up, put him on traction, and someone who is more used to this kind of stuff can do it on Monday—in the same way as I would do for a difficult proximal humorous, which I'm not happy treating. (42:00)

Take-home points

- Follow a protocol to properly diagnose (and avoid missing) femoral neck injuries.

- Stabilize the neck roughly to avoid displacing it (or further displacing it) while fixing the shaft. Once the shaft is stable, put it in traction and use the techniques Sommer demonstrated.

- Don’t do unnecessary open reductions on femoral neck injuries.

- Wherever possible, stick to minimally invasive techniques.

Total Hip Replacement for Fracture

By Xavier Griffin

Griffin (“Professor Xavier”) discusses how surgeons can use networked data and meta-analyses to amalgamate vast amounts of information and inform their treatment decisions. Focusing particularly on total hip replacements in fragile patients, he summarizes several layers of systematic reviews regarding total hip replacement surgery.

He begins with a computer-generated network plot that depicts the links between a set of ideas—in this case, surgeons’ preferences for total hip replacements vs cemented hemiarthroplasties. By showing not only the direct connections between the central ideas, but also indirect ones, e.g., linking groups of surgeons who use internal fixation nails or other types of arthroplasties, this computer-generated plot both informs the viewer and suggests further avenues for exploration.

Griffin goes on to discuss how the same plotting software can be used to do deeper-level analyses. After feeding in the data from 119 trials on the same subject, his group generated plots of three key outcomes:

- Unplanned returns to the theater

- Mortality

- Health-related QoL

This indicated that there was no evidence supporting the hypothesis that, regarding any of the outcomes of interest, total hip replacement produces different outcomes compared with a cemented modern unipolar hemiarthroplasty.

Pairwise comparison

Bearing in mind that the links shown so far have been rather general and should not be afforded too much weight, Griffin and his group went a level deeper to look at pairwise comparisons. To focus on studies comparing hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement, his group filtered first for hemiarthroplasty, narrowing the field of studies from 119 to 58; filtering again for comparisons between hemiarthroplasty and total hip replacement left 17.

Looking into those 17 studies, Griffin then reviewed differences in seven core outcomes: activities of day living, functional status, quality of life, mobility, mortality, delirium and unplanned returns to the operating theater. He chose these particular measures because, based on available survey data, both patients and methodologists considered them relevant:

We can measure appropriately inside the trials so that when we judge what is better. We are judging it in a way that patients and clinicians value. (54:35)

Diving deeper

To go one step further, Griffin then asked for a forest plot indicating the range of patients’ evaluations of how well their total hip replacements actually functioned. Of the seven measures for which Griffin generated similar plots, only one showed even a small significant advantage to using total hip replacement. None of the others showed any significant differences. I.e., this mini-meta-analysis indicates a situation of functional equipoise.

Very granular details

Finally, at the most granular level, Griffin looked at the data from the international standout Health Trial, for which 1500 participants were randomized, treated with either total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty and followed for 24 months.

HEALTH Investigators; Bhandari M, Einhorn TA, Guyatt G, Schemitsch EH, Zura RD, Sprague S, Frihagen F, Guerra-Farfán E, Kleinlugtenbelt YV, Poolman RW, Rangan A, Bzovsky S, Heels-Ansdell D, Thabane L, Walter SD, Devereaux PJ. Total Hip Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty for Hip Fracture. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 5;381(23):2199-2208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906190. Epub 2019 Sep 26. PMID: 31557429.

Based on data Griffin concludes that, for more fragile patients, for whom short-term outcomes often include mortality, the hemiarthroplasty group’s lower need for secondary procedures over roughly 15 months postoperatively is a noteworthy advantage. For younger and more resilient patients, he considers the total hip arthroplasty a more durable long-term choice.

He also offers a strong argument against rushing to fulfill an admission-to-treatment target, i.e., that the reason for a delay cannot be ignored. If a patient has to wait because of serious illness or polytrauma, that patient is starting at a very different point from another who is otherwise healthy but arrives on a Friday night and has to wait until Monday for a highly-skilled surgeon:

I would always say that to people that the evidence recommends get the right surgeon to do it in daylight hours with the right skill set. And if that means that your road to the patient waits more than 36 hours, then I think that's okay. (1:06:15)

Asked about predictors of high-quality patient outcomes, Griffin answers without hesitation:

The three predictors which, when combined and all delivered, the key things that improve mortality and quality life, are joint ortho-geriatric and surgical co-management, identification of delirium postoperatively, and a falls and future fracture prevention assessment by a specialist team…. So, if I had to summarize, the key thing that you can do for your patients if you're a surgeon is to recruit an ortho-geriatrician.

Improving outcomes for hip fracture care—an algorithm

By James Waddell

Waddell’s lecture is structured much more formally than any of the three that precede it. On the topic of hip fracture treatment outcomes, he focuses on the importance of incremental improvements that return patients to functionality, the broadest sign of which is their ability to return to their pre-injury living situations. And while he begins by telling us that his lecture is very general, he also manages to pack in an impressive amount of useful detail.

He begins by stressing the importance of a consensus on the terms of the discussion. The episode of care, for example, lasts from admission to discharge. For the care episode, he lists four outcome measures: time to surgery, weight bearing status, length of stay and discharge disposition. After discharge, three more remain to be recorded: readmission rates, 90-day mortality and 1-year mortality. In addition, each aspect of care can be rated in terms of effectiveness, appropriateness, integration, efficacy and access.

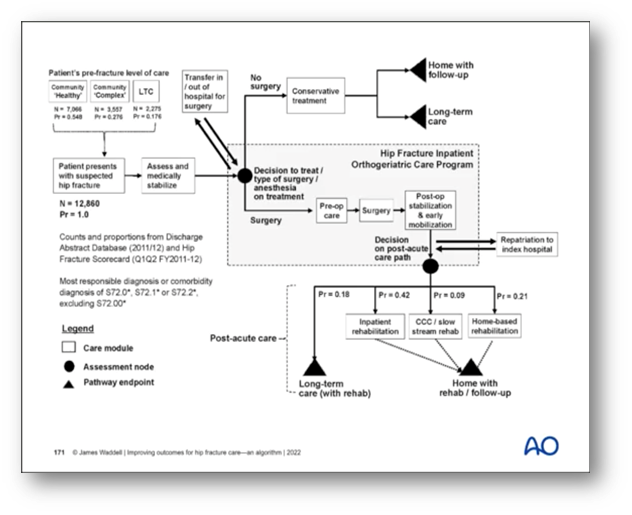

Waddell is also very aware of the characteristics of the elderly hip-fracture population, noting various factors, most notably a high prevalence of chronic illness but typically-low levels of social support. He stratifies those with active chronic illness who live in their own homes as complex at home. This group fall between those who are more and less independent—respectively the healthy at home and the nursing home (institutional) care groups.

The high cost of low-quality care

To provide all necessary aspects of care to all three groups, Waddell presents an algorithm (depicted below) which can be adapted for implementation to any hospital context. To illustrate its value, he cites the record of the Canadian province of Ontario, where it was first developed and implemented. In 2008, he recalls that “only a third of patients sustaining a hip fracture in Ontario were able to return to their pre-injury level of living in terms of their home.” The other two-thirds would be discharged to institutional settings funded partially or wholly by the provincial government.

In light of the extremely high costs of this system, Waddell’s group were asked to develop a program that would focus on enabling more hip fracture patients to return to their own homes.

In response, Waddell spearheaded a project to improve every aspect of care for these patients. As the chairman of the Health Quality Ontario Hip Fracture Committee, he oversaw the setting of higher standards across the board.

Quality Statements

To guide each site’s progress, the Committee defined quality statements on fifteen topics: 1. Emergency Department Management; 2. Surgery within 48 hours; 3. Multimodal Analgesia; 4. Surgery for Stable Intertrochanteric Fractures; 5. Surgery for Subtrochanteric or Intertrochanteric Fractures; 6. Surgery for Displaced Intracapsular Fractures; 7. Postoperative blood transfusions; 8. Weight Bearing as Tolerated; 9. Daily mobilization; 10. Screening for and Managing Delirium; 11. Postoperative Management; 12. Patient, Family and Caregiver Information; 13. Rehabilitation; 14. Osteoporosis Management; and 15. Follow-up Care.

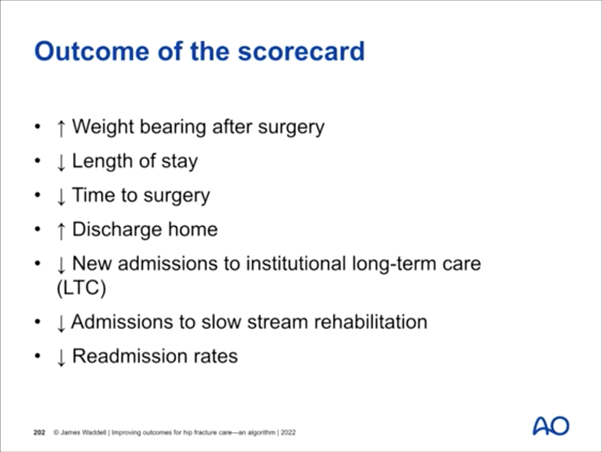

The program was tremendously successful: Today, not only have mortality rates dropped, almost two-thirds of patients who sustain a hip fracture are able to return to their previous living arrangements….This is measured on twelve thousand hip fracture patient that we’ve looked after.

However, Waddell also notes that not all hospitals observe the quality standards to the same degree. As a result, while both 30- and 90-day mortality rates have fallen across Ontario’s hospitals by roughly 1.5%, individual hospitals’ figures for 90-day mortality rates still range from 5% in the best to 22% in the worst.

Budget gains without quality losses

Another major outcome is that the mean length of stay has decreased by four days, while the readmission rate has remained stable. This suggests “that the patients are being discharged in an appropriate fashion.”

Similarly, to reduce the number of admissions to long-term care facilities, more patients are now receiving rehabilitation therapy first as in-patients, then after they return to their homes.

Regarding standardization of surgical techniques, Waddell has had less success. Despite guidelines regarding the use of intramedullary nails, for example, some hospitals continue to use nothing else.

Positive scorecard

Toward the end of his lecture, Waddell shows a scorecard indicating improvements on all major points. Based on data from 11000 patients, this card’s headings generally follow the consensus points Waddell started with; however, the number of discharge options has increased to include more rehabilitation options, and the 30- and 90-day mortality figures have been omitted.

Waddell concludes his presentation (but not his lecture) with three points (below) on ensuring his program’s implementation, hospital-level compliance and key indicators for the program’s success, particularly regarding mortality, length of stay, readmission and the numbers of patients who can return to their primary residences.

Perioperative care gives patients years of function

Following his presentation, in response to a comment on the value of patient co-management, Waddell speaks of what, from the patient perspective, is likely the most important measure of progress: I think many of us, the older surgeons here, were trained to think, "Well, hip fracture's an end-of-life event." And you do an operation to try and manage their pain or discomfort without any thought of trying to restore function. And over the last 20 years, it's been becoming increasingly evident that with the right kind of care, including the right operation, but more importantly, I think, the better perioperative care, many of these people can go home and continue a very functional, very productive life.

AO Trauma is deeply grateful to these speakers for generously sharing their time and expertise in this webinar, and to moderators Hans-Christoph Pape and Vikas Khanduja for running the webinar.

Watch a video recording of the original AO webinar.

About the authors

Christoph Sommer is a past president of the Swiss AO and has been a member of the AO technical committee since 2006. He is highly experienced in the development of periprosthetic plates, and collaborated on the implant he discusses in this Webinar.

Peter Bates is a consultant at the Royal London Hospital where he is also a senior lecturer and co-chair for orthopedic trauma, and a co-founder for Orthohub. Bates has also been involved in the development of proximal femoral implants.

Xavier Griffin is the chair of Bone and Joint Health the at the Blizard Institute at Queen Mary and Barts Health University of London.

James Waddell is the Secretary General of SICOT. He is a staff surgeon at St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, Chief of Orthopedics, Chief of Surgery, and Head of the Trauma Program. He also serves as the Clinical Lead for Orthopedic Surgery in the Province of Ontario.

References

- Alho A. Concurrent ipsilateral fractures of the hip and femoral shaft: a meta-analysis of 659 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996 Feb;67(1):19-28. doi: 10.3109/17453679608995603. PMID: 8615096.

- Marins MHT, Pallone LV, Vaz BAS, Ferreira AM, Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Salim R, Fogagnolo F. Ipsilateral femoral neck and shaft fractures. When do we need further image screening of the hip? Injury. 2021 Jul;52 Suppl 3:S65-S69. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.01.040. Epub 2021 Jun 1. PMID: 34083022.

- Op cit. Alho, A, 1997

- Gupta A, Jain A, Mittal S, Chowdhury B, Trikha V. Ipsilateral femoral neck and shaft fractures: case series from a single Level-I trauma centre and review of literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2023 May;33(4):803-809. doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-03199-3. Epub 2022 Feb 4. PMID: 35119486.

You might also be interested in:

AO Trauma courses and events

AO Trauma provides accredited and high quality educational activities to thousands of surgeons and health care professionals each year. Find your next learning activity in your region.

AO Surgery Reference

AO Surgery Reference is a resource for the management of fractures, based on current clinical principles, practices and available evidence.

Master the treatment of lower extremity trauma

The AO Trauma curriculum courses provide a modular framework for teaching the current management of patient problems related to trauma of the lower limb.

AO Trauma Guest Blog

Find more insights form the AO Trauma community, or submit your own guest post proposal. Advancing trauma care and your career, one story at a time.