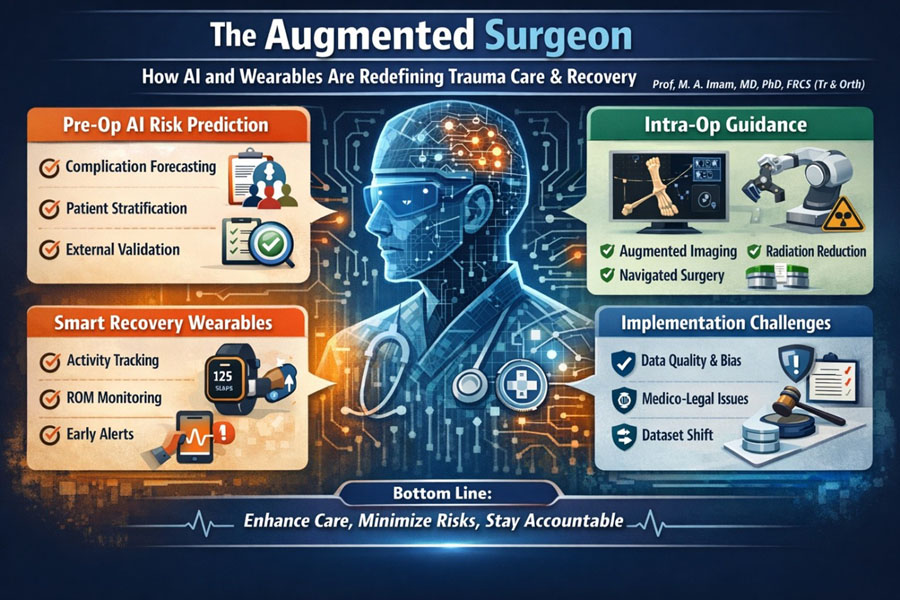

The augmented surgeon: how AI and wearables are redefining trauma care and recovery

BY PROFESSOR M. A. IMAM

Trauma care is a chain of time-critical decisions made under uncertainty: triage, imaging choices, operative timing, approach and implant selection, rehabilitation intensity, and follow-up cadence. The challenge is not that surgeons lack knowledge; it’s that the signal is scattered across imaging, comorbidities, injury patterns, social constraints, rehab access, and adherence.

Here, I will explore practical ways to use prediction, navigation, and remote monitoring without losing the basics.

-

Read the quick summary:

- AI planning is moving trauma teams from classification to risk prediction, flagging patients at higher risk of complications, stiffness, prolonged disability, or readmission before the first incision.

- Intra-operative guidance (navigation / augmented imaging/decision support) can improve technical precision and reduce fluoroscopy burden, but it can also fail in predictable ways (workflow friction, registration errors, poor generalizability).

- Wearables and motion sensors are becoming practical tools for tracking objective recovery activity and range of motion (ROM) trends, helping teams detect early “off-track” trajectories and intervene sooner.

- Implementation is the hard part: data quality, external validation, dataset shift, bias/fairness, medico-legal responsibility, and governance must be designed in, not bolted on later.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

Why the “augmented surgeon” matters in trauma (and why now)

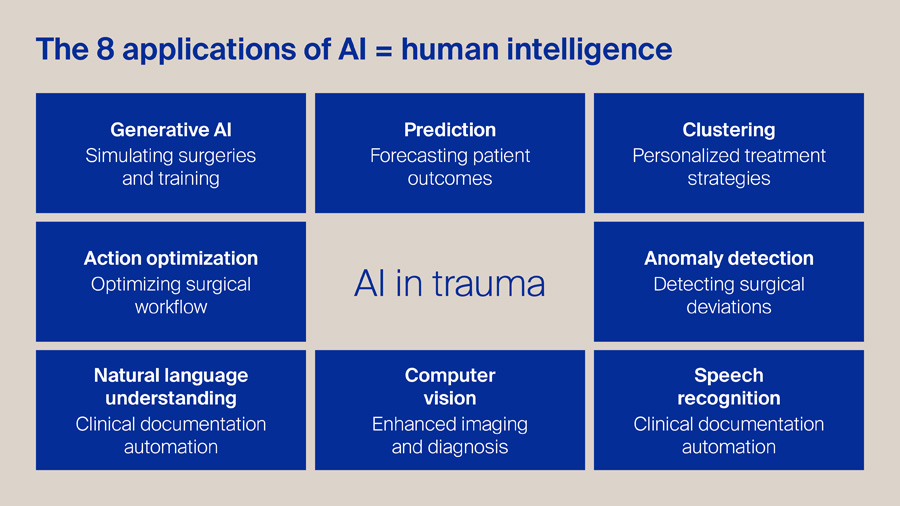

For me, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a clone of human intelligence. In my view, this graphic captures the most practical way to think about AI in trauma: not as a single tool, but as a set of human-like capabilities that can support every step of the pathway.

Generative AI can accelerate surgical education through realistic simulation and rehearsal, while prediction models help us forecast outcomes and anticipate complications earlier. Clustering allows us to move beyond one-size-fits-all protocols towards genuinely personalized strategies, and action optimization can streamline theatre flow, staffing, and peri-operative decision-making. In parallel, anomaly detection offers a safety net, flagging deviations in technique, physiology, or workflow that may precede harm. On the clinical side, natural language understanding and speech recognition can reduce documentation burden and improve the completeness of records, freeing clinicians to focus on patients.

Finally, computer vision strengthens imaging interpretation and intra-operative guidance. The opportunity is substantial, but the principle remains simple: AI should amplify clinical judgement, improve safety, and reduce waste—while staying transparent, validated, and firmly under human oversight.

Augmentation in this context means turning fragmented data into actionable, pathway-level decisions while keeping accountability with the clinical team. That is also why the AO lens matters: AO principles reward precision and early mobilization, but long-term outcomes depend on much more than union.

Pre-op intelligence: from classification to risk prediction

Fracture classification and operative indications remain foundational, but they do not reliably tell us who will develop infection, nonunion, stiffness, prolonged opioid use, delayed return-to-work, or repeated ED visits. What has changed is the feasibility of combining multiple weak signals into a risk estimate that can shape early decisions:

1) Complication forecasting that changes the plan (not the PowerPoint)

A practical risk model is only useful if it changes something real: antibiotic strategy, timing to theatre, fixation method, soft-tissue pathway, discharge planning, or follow-up intensity. In trauma, even small shifts matter, e.g., earlier escalation for high-risk wounds or tighter early ROM surveillance for a patient at high stiffness risk.

The quality bar is rising. Prediction tools increasingly need clear reporting, transparent validation, and evidence of real-world benefit, not just a high AUC on a convenient dataset. Reporting frameworks such as TRIPOD+AI exist for this reason [1].

2) External validation is the difference between “promising” and “safe”

Many models perform well in their native environments and underperform elsewhere. This is not a minor technicality; it’s a patient safety issue. External validation and careful implementation planning are repeatedly emphasized in the prediction-model literature [2].

Orthopaedics is not immune: systematic reviews have highlighted limitations in the availability and reporting quality of external validations for ML models in orthopaedic surgical outcomes [3].

3) Beware dataset shift: the silent failure mode

Trauma systems change implants, protocols, rehab access, imaging, and coding. A model trained last year can drift this year. The concept of dataset shift, with its performance drop due to a mismatch between training and deployment data, has been clearly described in clinical AI and should be part of every deployment plan [4].

Bottom line: Pre-op AI should be treated like any other clinical tool: transparent development, external validation, and a monitoring plan for drift—otherwise it becomes “false reassurance at scale” [1].

Intra-op precision: reduction accuracy, decision support, radiation minimization and where it fails

Intra-operative augmentation spans a spectrum: from simple tools that reduce fluoroscopy shots to fully navigated or robotic workflows.

1) Where intra-op augmentation helps (when it’s designed for the workflow)

Navigation and augmented imaging can improve implant placement accuracy in selected tasks and may reduce radiation exposure/fluoroscopy burden in certain settings, especially where anatomy is complex and fluoroscopy time is high. Systematic reviews in areas such as navigated percutaneous sacroiliac screw fixation summarize this evolving evidence.

Radiation exposure in orthopaedic trauma is a real occupational and patient issue; quantifying and reducing it is a legitimate clinical gain, not a “nice-to-have [5,6].”

2) Where it fails (predictably)

Intra-op systems fail less often because “AI is bad” and more often because the operating room is not a lab:

- Registration and alignment errors: if the system’s map of anatomy drifts from reality, precision becomes confidently wrong.

- Workflow burden: extra steps, equipment, and staff training can erase benefits in high-throughput trauma lists.

- Edge cases: obesity, unusual anatomy, comminution, poor imaging windows, or unplanned changes mid-case can break assumptions.

- Over-trust: the more polished the interface, the easier it is for teams to stop interrogating outputs.

A healthy stance is “trust but verify.” Augmentation should shorten the distance from plan to execution, not replace intra-operative judgement.

3) Evidence standards still apply

If the intra-op tool is effectively an intervention, it should be evaluated and reported with rigor. In AI-enabled interventions, CONSORT-AI extends trial reporting expectations; DECIDE-AI supports responsible early-stage live clinical evaluation [7].

Smart recovery: objective metrics for ROM, activity, adherence, and early warnings

Trauma follow-up often relies on episodic clinic snapshots and subjective impressions. Yet recovery is a time series. Wearables and motion sensors are valuable because they convert recovery into trend data that can trigger earlier action.

1) What can we measure today (without building a research lab)?

- Activity and sedentary time (step count, active minutes, sit-to-stand patterns)

- Upper limb ROM proxies using inertial measurement units (IMUs) or validated motion-tracking approaches

- Adherence signals (did the patient move, did they progress, are they plateauing?)

Evidence suggests wearable activity-tracker interventions during hospitalization can increase activity and improve physical function metrics, even if some broader outcomes (like length of stay) do not always change [8].

For upper limb assessment, IMUs have been systematically evaluated for concurrent validity in measuring ROM in adults, supporting their role as practical measurement tools when used appropriately [9].

2) Rehab augmentation: promising, but we must stay honest

A key practical message from systematic reviews is that commercially available wearables may support rehabilitation as an adjunct, but the evidence base still needs better-designed studies and clearer economic evaluations before claims of widespread adoption are justified [10].

So, the realistic aim is not “a smartwatch replaces physiotherapy.” It is to identify patients drifting off the expected recovery slope earlier, and deploy targeted interventions sooner (extra physio contact, analgesia optimization, stiffness protocol, social support, transport solutions, or expedited review)./p>

3) Early warning needs clinically meaningful thresholds

The most useful outputs are not raw data dashboards. They are actionable thresholds linked to agreed pathways:

- plateau in ROM progression for X days after a defined injury/operation

- sustained low activity relative to expected trajectory

- abrupt drop suggesting pain flare, fear avoidance, or complication

This requires consensus on outcomes that matter (function, return-to-work, independence), not just what sensors can easily count.

Implementation reality: what blocks adoption

This is where most well-meaning innovations stall.

1) Data quality and governance are not optional

If input data are biased, incomplete, or inconsistently captured, outputs will be unreliable. Governance guidance emphasizes ethics and human rights, accountability, and transparency in health AI [11].

2) Bias, fairness, and equity must be engineered in

Health AI can amplify disparities if models perform differently across groups or if deployment assumes equal access to follow-up, rehabilitation, and technology. Reviews on fairness in healthcare AI outline concerns and mitigation strategies, and should be part of “AI literacy” for clinical leaders [12].

3) Medico-legal clarity: who is responsible?

If a system influences decisions (triage, implant choice, discharge), teams need clarity: is it decision support or an autonomous recommendation? Regulatory guidance for clinical decision support software (and its boundaries) keeps evolving; staying aligned with current guidance is essential [13].

4) Evidence expectations should match risk

Not every digital tool needs an RCT—but higher-risk tools need stronger evidence. The NICE Evidence Standards Framework is one example of a tiered approach to evidence expectations for digital health technologies [14].

5) Reporting and evaluation frameworks exist—use them

- TRIPOD+AI for prediction model studies [1]

- DECIDE-AI for early live clinical evaluation [15]

- CONSORT-AI for AI intervention trials [16]

Using these does not slow progress; it reduces the risk of deploying confident tools that do not generalize.

Monday-morning checklist: 5 practical steps a trauma unit can do now

- Pick one pathway problem (not one gadget). Example: early stiffness after upper limb fixation, or prolonged immobility in older trauma admissions.

- Define 2–3 outcomes that matter (e.g., ROM trajectory, function milestone, unplanned contact/readmission).

- Start with a measurement you can sustain: a simple wearable activity metric for inpatients, or IMU-based ROM checks for a focused subgroup.

- Demand external validation/monitoring for any risk model you adopt, and plan for dataset shift (who watches drift, how often, what triggers review).

- Build governance into the rollout: consent approach, data security, role clarity, and an equity check (who benefits, who is left behind).

Future questions AO should help answer

- Which outcomes truly define success after trauma? Union is necessary but not sufficient, participation and durable independence matter.

- What is the right “minimal dataset” for trauma augmentation? Registries and routine systems should capture what’s predictive and actionable, not just what’s billable.

- How do we validate across settings? External validation across hospitals, countries, and resource levels is essential to avoid bias from exporting.

- How do we ensure equity? If wearables improve monitoring but only for patients who can afford devices or smartphones, disparities widen.

- What is the governance model for continuous learning? Trauma pathways evolve; our tools must be monitored and updated safely.

About the author:

References

-

TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods | EQUATOR Network [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 15]. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/tripod-statement/. Accessed 15 Jan 2026

-

Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, Debray TPA, Altman DG, Moons KGM, et al. External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: opportunities and challenges. BMJ. 2016;i3140. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3140

-

Groot OQ, Bindels BJJ, Ogink PT, Kapoor ND, Twining PK, Collins AK, et al. Availability and reporting quality of external validations of machine-learning prediction models with orthopedic surgical outcomes: a systematic review. Acta Orthopaedica. 2021;92:385–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2021.1910448

-

Finlayson SG, Subbaswamy A, Singh K, Bowers J, Kupke A, Zittrain J, et al. The Clinician and Dataset Shift in Artificial Intelligence. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:283–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2104626

-

Haveman RA, Buchmann L, Haefeli PC, Beeres FJP, Babst R, Link B-C, et al. Accuracy in navigated percutaneous sacroiliac screw fixation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2025;25:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-025-02813-z

-

Rashid MS, Aziz S, Haydar S, Fleming SS, Datta A. Intra-operative fluoroscopic radiation exposure in orthopaedic trauma theatre. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-017-2020-y

-

Liu X, Cruz Rivera S, Moher D, Calvert MJ, Denniston AK. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nat Med. Nature Publishing Group; 2020;26:1364–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1034-x

-

Szeto K, Arnold J, Singh B, Gower B, Simpson CEM, Maher C. Interventions Using Wearable Activity Trackers to Improve Patient Physical Activity and Other Outcomes in Adults Who Are Hospitalized: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2318478. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18478

-

Li J, Qiu F, Gan L, Chou L-S. Concurrent validity of inertial measurement units in range of motion measurements of upper extremity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wearable Technol. 2024;5:e11. https://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2024.6

-

Latif A, Al Janabi HF, Joshi M, Fusari G, Shepherd L, Darzi A, et al. Use of commercially available wearable devices for physical rehabilitation in healthcare: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e084086. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084086

-

Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 15]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200. Accessed 15 Jan 2026

-

Ueda D, Kakinuma T, Fujita S, Kamagata K, Fushimi Y, Ito R, et al. Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: review and recommendations. Jpn J Radiol. 2024;42:3–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-023-01474-3

-

Clinical Decision Support Software | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 15]. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-decision-support-software. Accessed 15 Jan 2026

-

Overview | Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2018 [cited 2026 Jan 15]. https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd7. Accessed 15 Jan 2026

-

Vasey B, Nagendran M, Campbell B, Clifton DA, Collins GS, Denaxas S, et al. Reporting guideline for the early-stage clinical evaluation of decision support systems driven by artificial intelligence: DECIDE-AI. Nat Med. Nature Publishing Group; 2022;28:924–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01772-9

-

Liu X, Cruz Rivera S, Moher D, Calvert MJ, Denniston AK, SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI Working Group. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nat Med. 2020;26:1364–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1034-x

Suggested further reading (high yield):

- TRIPOD+AI reporting guideline for prediction models using regression/ML

- CONSORT-AI extension for trials of AI interventions

- DECIDE-AI guideline for early-stage clinical evaluation

- WHO: Ethics and governance of AI for health (2021)

- Finlayson et al. Dataset shift in clinical AI (NEJM)

- Latif et al. Consumer-grade wearables in rehabilitation (BMJ Open)

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Funding: None.

Use of AI tools: A Claude opus 4.5 thinking model was used to support initial drafting and editing. All content was reviewed, fact-checked, and finalized by the author.

You might also be interested in...

Courses and events

AO Trauma is renowned for its professional courses targeted at orthopedic trauma surgeons and operating room personnel (ORP).

AO Companion

Learn smarter with peer-reviewed knowledge, AI-driven summaries, and interactive tools in one app.

Clinical library and tools

Explore our resources designed to develop your competencies, improve patient care, and help you build your career.

AO Trauma faculty

The passion and dedication of faculty are the driving forces behind the outstanding reputation of AO Trauma’s educational offerings.