AO Sports steering board chair James Stannard on new AO Sports curriculum, including Principles and Masters courses

Langdon A. Hartsock, MD: Tell me, from a global AO perspective and then in regards to North America, how did sports medicine get off the ground?

James Stannard, MD: Many significant soft tissue injuries around joints occur from high energy traumas, so some of us have morphed to where we take care of both, and it's become an area of interest for a number of surgeons.

I think the unique part of the ability to do both is that there are a lot of these injuries in motorcycle and motor vehicle collisions—we understand how to work around the implants when the patient has a fracture.

We've done a couple of knee courses over the years in Davos with a group including Mauricio Kfuri, me, and Joe Schatzker, comprehensively hitting the need to include ligaments and meniscus.

These courses have done well, and Mauricio Kfuri, when he was back in Brazil, ran a successful every-other-year course—the last one drew 800 surgeons—that was a comprehensive knee course including things like plateau fractures, but it was heavily focused on sports with a little bit of recon.

Right as the pandemic was starting, we made the decision to do a trial initiative. DePuy Synthes was willing to put forth some money, develop some courses, get it going, and then decide later whether this would become a long-term initiative like AO Recon.

We did a knee course in Davos last December. We’ve had some issues putting on these previous Sports events because of the pandemic, but now we’re poised for our next set of courses.

We've had a knee group developing a knee masters course and a shoulder group developing the Shoulder Masters Course. I’m the AO Sports steering board chair, but I’ve also been involved in developing a Principles of Sports Medicine.

There are certainly lots of societies that have had masters or advanced-type courses for knee or shoulder, but I’m not aware of anything that's really tried to look at the principles behind the concept of sports medicine.

We're getting ready to do our first Principles of Sports Medicine in Denver in August and we have another one scheduled for Davos in December, then five or six of them on the books for 2023.

This course excites me the most because it is totally unique, and I hope it will do for sports what I feel like the Basic Principles of Fracture Management course did for trauma, which is eventually become a regular part of a number of residencies.

On the international level, there's a goal of around ten courses in 2023.

Hartsock: Tell me a little bit more about the Principles course.

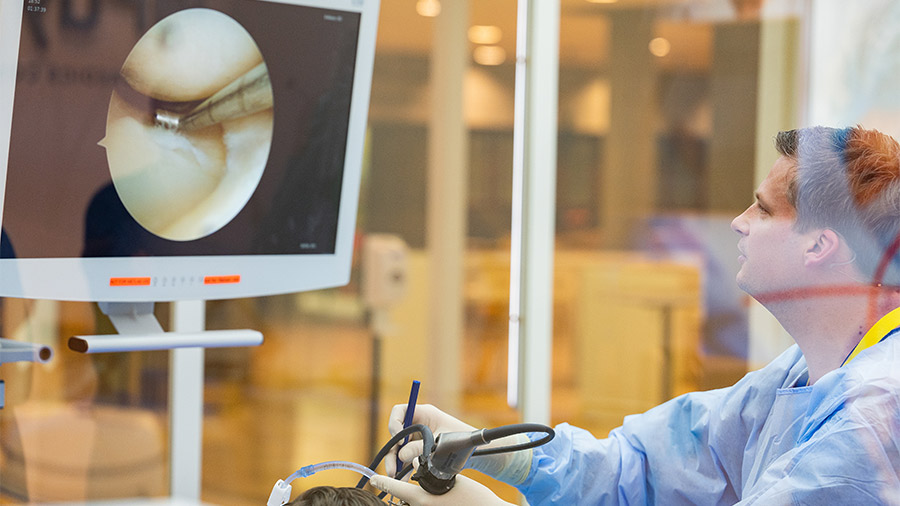

Stannard: It's designed as a two-day course. We’ve been collaborating with a company called Tactile Orthopedics that has developed a very realistic knee model, and at the Denver course they will release their shoulder model.

It's a dry scope: you're looking at a TV screen and holding the scope but it's a model on the inside. You can put a probe in and touch it, unlike the simulators where everything's in space. You can do an ACL on it; you can do a repair on it. Those are way more affordable, so we're going to use those heavily as well as some models we've developed with Synbone to allow for things like techniques of meniscus repair and knot tying.

There will be about six online lectures we're asking participants to watch and learn from before coming to the course. The in-person component is heavily model-, practical-, and case-oriented, with a limited amount of us lecturing at them.

I think PG 3-5 and fellows will benefit the most—people who are getting along a bit and have already done a Principles of Fracture Management course and now are interested in sports.

Hartsock: What are you covering in the Principles of Sports curriculum?

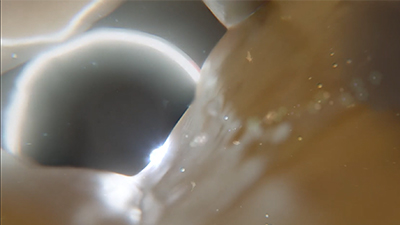

Stannard: It's baseline principles. The pre-course stuff includes what is tendon, what's its function, what's it made of, how about articular cartilage—those sorts of things. Then we start the course with a three-dimensional video tour through the knee in which we, the audience, are microscopic, somewhat modeled after the movie The Incredible Journey.

We're going to go inside the knee and see the patella moving up and down in the trochlea, see the shape of it and why that's important, and then later we'll have it show “Okay, now you’ve torn your media patella femoral ligament, look at it: it's dislocating over here and now it's causing damage to the cartilage.” We will show a Zamboni machine on it, because articular cartilage is a thousand times more slippery than wet ice.

We're trying to get them excited about the whole idea at the opening the course. It's called Principles of Sports Medicine—the Joint Is an Organ, and the idea that you've got all these different structures working together in a joint: meniscus, articular cartilage, ligaments, tendons, synovium, all interplaying to create one thing. If any of it goes wrong, the whole thing starts to not function.

We’re going to show the concept of these different things working together like a symphony. One of our course designers from Germany recorded their local orchestra playing a piece, showing just how beautiful it is when it’s all working together. Then he had them untune their instruments and play out of time to show how bad it can sound when it’s not all together.

From there we'll start going into aspects like meniscal repair. We won't be going heavily into the major ligamentous reconstructions—that would be more for the advanced course, but we will cover the function of these things, why they're important, and how they heal, providing the background behind what would hopefully be the practice of sports medicine.

Hartsock: Do you hit on any kind of general principles of sports medicine, such as sideline coverage, etc.?

Stannard: We do—there's going to be a lecture on working as a team physician and how you interact with the player versus the coach versus the parents versus, sometimes, the agent.

Eric McCarty is the head team doctor for the University of Colorado and has been for 25 years, he’s going to provide that first lecture for us.

Hartsock: How about the faculty for these events?

Stannard: It’s interesting: how do you get some of these folks to faculty education programs and things that didn’t exist when you and I came through at the beginning?

I remember being involved in the first efforts to teach it when nobody had ever taught me, so right now we’ve got one group of faculty like me, including Mauricio Kfuri, Christoph Katthagen in Germany, and Saeed Al Tahani in the Middle East in Dubai, and then another group who did AO courses when they were residents but they've not had any involvement with AO since.

For instance, of the ten faculty for Denver, six are from this second group: Seth Sherman from Stanford, Miho Tanaka from Harvard, Volker Musahl from Pittsburgh, Rachel Frank from Denver, Steven DeFroda from MU, and Eric McCarty from University of Colorado. It’s a really good group.

Some of those I have personal relationships with, and I was able to say “Hey, can we get you excited about maybe taking on something?” August is tight because of the number of state football teams, but it's interesting how excited some of these sports surgeons have been because they had good experiences with AO educationally but went into another field.

They're excited about the concept of “Wow, if we could do the education part like what is done for trauma, that would be pretty cool.”

Hartsock: Where do you see this going - where's it headed?

Stannard: I see it rolling out with a suite of three things: principles, advanced, and then masters. Right now, we are going to stay focused mostly on the shoulder and knee, but eventually you might get into hip or ankle.

After the principles course, we’re looking to establish advanced courses with some of these cool models—doing a double bundle PCL in this course, doing a posterior medial corner and posterior lateral corner in that course, with similar things offered for the shoulder.

Then a masters level cadaver course—one per year in North America, whereas I would see a couple of advanced and four or so principles.

This year we are offering a masters-level shoulder course in Boston, Massachusetts September 24-25. The first day of the course will be in conjunction with the OSET conference and the second day will be at the Raynham Learning Skills Center.

We have taken on trying to get this going in North America, which is a tough area to get courses going in, maybe even tougher with the pandemic. I’m interested to see if we can gain a good attendance for this first course in Denver. I’m very hopeful, but we'll know soon.

Related pages

Biceps tenodesis

AO Sports faculty and course co-chair Amon Ferry puts a spotlight on how to treat long head biceps tendon (LHBT) pathology

AO Sports offers a first-person look at knee and shoulder pathology

Watch the teaser video and learn more about the upcoming AO Sports Principles course