Removing barriers in the OR: rethinking ergonomics for surgeons with smaller hands

BY DR SUSANA NÚÑEZ PEREIRA

When we talk about surgical innovation, most of the attention falls on new technologies, advanced imaging, or novel implant designs. What we do not talk about enough are the tools in our hands every day. While surgical instruments have remained essentially unchanged in form for decades, they remain central to how we deliver care. An often-overlooked aspect is that many of these instruments are designed for the “average” surgeon, without considering the wide diversity in hand size and ergonomics among operating surgeons.

This oversight can have real clinical and professional consequences. For many of us, the challenge is subtle and often goes unrecognized. But once identified, it reveals a broader issue that calls for awareness and change.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Dr Susana Núñez Pereira highlights how standard surgical instruments are typically designed for the average male hand (≈19 cm), creating ergonomic barriers for surgeons with smaller hands.

- Oversized instruments can reduce dexterity, increase fatigue, cause awkward grip positions, and contribute to misperceptions of surgical skill, particularly affecting women and trainees.

- Addressing these limitations through adjustable or multiple handle sizes could improve precision, safety, and inclusivity in spine surgery.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

A personal experience in the OR

I do consider myself an average skilled surgeon, not especially skilled, not especially clumsy. A couple of years ago, I found myself performing an implant removal on a patient from a system I had not used in a while. This system has a clamp you need in order to unlock the screws from the rod. I quickly realized that I could not generate the necessary closing force, not because I lacked arm strength, but because my hands could not properly grip the instrument.

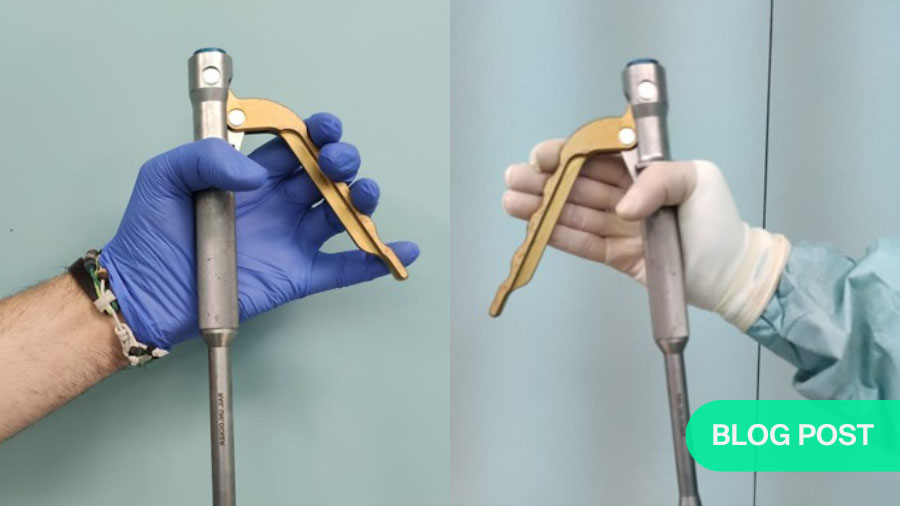

At just over 6.2 inches (16 cm), my hand size falls below the average considered in most design contexts. The clamp’s size meant that simply holding it absorbed most of my attention and effort, leaving little freedom to apply proper force. My grip was awkward, my thumb bent in a compensatory position, and it was hard to control the instrument with precision. I even took a picture, which shows that the tip of my little finger isn’t visible. My thumb is flexed because, if it were more extended, I wouldn’t be able to hold the instrument properly. My whole hand is gripping the instrument at its narrowest part, leaving no free space above.

After finishing surgery, I asked a colleague with larger hands to hold the same instrument so we could compare. The difference was striking: his grip was natural and stable. That was the first time I began questioning why these discrepancies in instrument design were not discussed more openly.

One size does not fit all

The world of sports often provides useful metaphors for surgery. In tennis, rackets are available in multiple grip sizes to match individual hands. Even a subtle mismatch can impair control, increase fatigue, and risk injury. Golf follows a similar principle. Yet in surgery, where performance is directly tied to patient safety, we continue to accept a “one size fits all” approach.

Surgical instruments are sized for the average male hand, which measures around 7.5 inches (19 cm). That benchmark has guided the design of most instruments historically. But what happens to those with smaller hands? Tasks can require more effort, compromise dexterity, and create awkward positions. Over time, this may lead to fatigue, discomfort, or even musculoskeletal issues. According to Basager et al. (2024), people with smaller glove sizes reported these issues more frequently, and such challenges might discourage aspiring surgeons from pursuing procedural specialties.

For me, I started to observe every instrument, and I realized for instance, that I can only use the distal phalanxes to press the Kerrison rongeur while my colleagues use the middle phalanxes. This is when I suddenly understood that there was an extra struggle in almost every surgical step and that I had slowly adapted to it. Yet, because the discrepancy is invisible to others, these surgeons may be unfairly perceived as less able. Since then, one of my goals has been to raise awareness about this disadvantage.

Implications for training and career development

The hidden cost of ignoring ergonomics can extend beyond personal frustration. Young surgeons with smaller hands may feel that they are clumsier or less able, when in fact they are just struggling with ergonomic barriers. This misperception risks shaping career choices in ways unrelated to actual ability.

From an educational standpoint, faculty must also reflect on unconscious biases. When we observe a trainee struggling, it is tempting to interpret the difficulty as inexperience or clumsiness. But sometimes the problem lies not in their technique, but in the ergonomics of the tools they are given. By recognizing this, teaching surgeons can foster a more inclusive and supportive environment for all trainees.

Moving toward better design in surgical instruments

A 2014 survey by Sutton et al. found that 86.5% of women performing minimally invasive surgery experienced physical discomfort, with women more likely than men to need treatment for hand issues. A decade later, recent research shows that female surgeons are still disproportionately affected by poor ergonomic design (White et al., 2024).

Correctly sized handles and grips could reduce unnecessary strain and improve precision. Adjustable grips could provide another solution, allowing surgeons to select the fit that works for them before beginning a case. Standard sets could include at least two handle sizes for commonly used instruments, just as we have left- and right-handed versions of certain tools. This might allow instruments to adapt to the user rather than forcing the user to adapt to them. In other fields, such considerations are standard. In surgery, they remain underdeveloped despite the intuitive benefits for patient safety and surgeon performance.

Addressing this gap will not be simple, but it is necessary. Medical device companies often focus on innovation at the macro level. Adding different instrument sizes may seem like a minor detail, but it would represent a meaningful step toward inclusivity in our field. As highlighted by Basager et al. (2024), ergonomic tool design improvements are urgently needed to protect the health and safety of both surgeons and patients.

Hospitals and surgical societies also have an important role to play. By raising awareness of these ergonomic barriers, we can encourage manufacturers to adapt. Feedback during product evaluations should include not only device performance but also accessibility for surgeons of varying hand sizes.

A call to awareness and access to instruments that truly fit

The first step in creating change is acknowledging the problem. As surgeons, we often pride ourselves on adapting to whatever situation arises. We learn to make do with inadequate lighting, noisy ORs, or instruments that do not quite fit our hands. But adaptation should not mean resignation to unnecessary barriers.

Surgical excellence depends on precision, endurance, and skill. All three can be compromised when the basic tools of our trade are designed for only one type of user. The time has come to move away from the “one size fits all” paradigm. We should instead embrace ergonomic inclusivity as an essential part of surgical progress.

If tennis players can select the correct racket handle and golfers can choose the proper grip, surgeons should also have access to instruments that truly fit. Our patients, our colleagues, and the next generation of surgeons deserve nothing less.

About the author:

References and further reading:

- Basager, A., Williams, Q., Hanneke, R., Sanaka, A., & Weinreich, H. M. (2024). Musculoskeletal disorders and discomfort for female surgeons or surgeons with small hand size when using hand-held surgical instruments: a systematic review. Systematic reviews, 13(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02462-y

- Sutton, E., Irvin, M., Zeigler, C., Lee, G., & Park, A. (2014). The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surgical endoscopy, 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3281-0

- White, A. J., Nowacki, A. S., Woodrow, S. I., Steinmetz, M. P., & Benzil, D. L. (2024). Ergonomics, musculoskeletal disorders, and surgeon gender in spine surgery: a survey of practicing spine surgeons. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine, 40(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.3171/2023.11.SPINE23705

You might also be interested in:

AO Access—diversity, inclusion, and mentorship programs

A visionary initiative for the organization’s commitment to becoming a diverse and inclusive organization with equal access and opportunity for all.

Empowering young females to become spine surgeons

When women think about becoming a surgeon, it is often accompanied by doubts and concerns. Yet orthopaedic surgery and especially spine surgery is a wonderful profession.

Innovation in spine surgery requires greater diversity

How does an aptitude for innovation translate to lasting and meaningful innovation? It starts with diversity; be it of age, profession, culture, disability, or any other.