Innovation in spine surgery requires greater diversity

BY DR BEN DAVIES

Do you consider yourself an innovator? Most spine surgeons would—developing and applying new approaches to improve care on a day-by-day basis is part of the role. This fundamental nature is reflected in high-performing metrics for innovation within the specialty, such as patents [1]. But how does an aptitude for innovation translate to lasting and meaningful innovation? I have come to believe it starts with diversity; be it of age, profession, culture, disability, or any other.

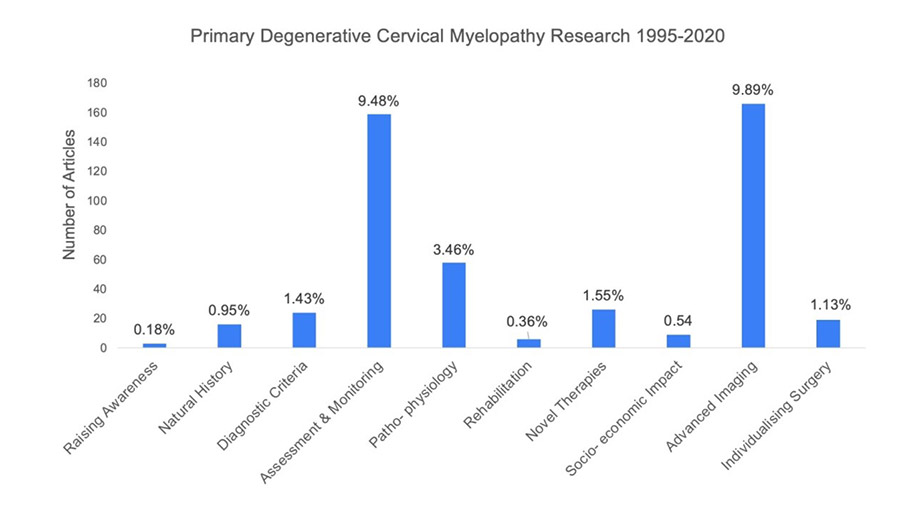

This month we publish a Special Issue of the Global Spine Journal, showing how a diverse group of professionals working with patients (429 people, across 68 countries and 17 different healthcare specialties) came together to expose and prioritize underappreciated problems, and develop a new research direction for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy (DCM), as part of AO Spine RECODE-DCM. As shown in the figure below, these questions have not historically been a focus for DCM research, which perhaps reflects a previous predominance of the surgeon perspective. The innovative study design, with diversity of input at its core, has delivered pivotal insights into DCM from the full complement of those living and working with the condition.

In his book, ‘Creativity Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration’, Ed Catmull, founder of Pixar, reflects on his personal quest to deliver sustainable innovation. He argues “Getting the right people and the right chemistry is more important than getting the right idea.” Within this environment it is becoming clear that diversity is critical. In his latest book, ‘Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment’, Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman and colleagues demonstrate how heterogeneity drives variation in human judgment, a phenomenon they term ‘noise’. Whilst the book largely focuses on the negative consequences of this (e.g., through inconsistent sentencing by judges, selection by recruiters, or decisions between doctors), they also acknowledge where noise is desirable: innovation.

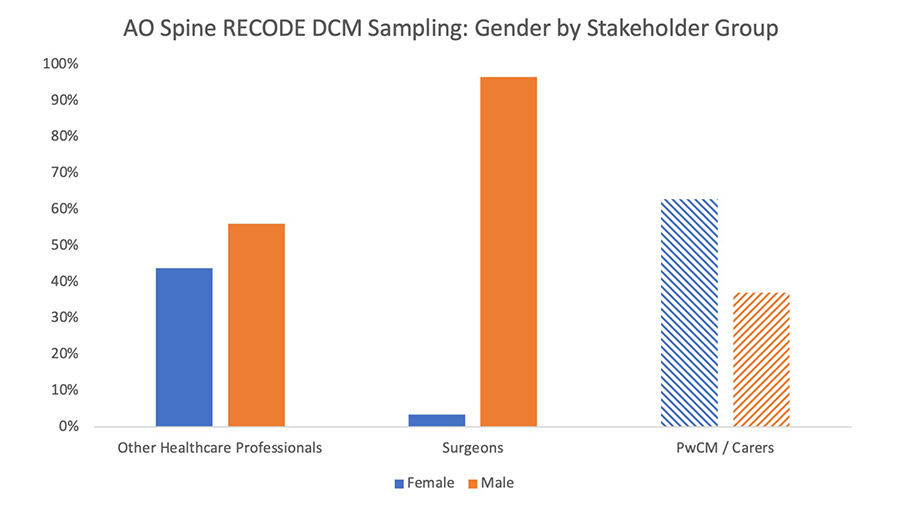

By contrast, spine surgeons lack diversity; we are a relatively homogenous group. For example, open-source data suggests that 97% of spine surgeons globally are male [3–7]. This accords with the sampling data from the AO Spine RECODE-DCM initiative and starkly contrasts with other medical specialties.

Gender diversity is a topical diversity issue. Historically seen as ‘just’ an inequality, stark evidence is building of its negative consequences. For example, in a comparative analysis of national responses to COVID19, nations under female leadership appeared to take a more aggressive approach to implementing population restrictions, and, at the end of the first wave, had the lowest COVID19 mortality [8]. And closer to home in the field of surgery, published this month in JAMA Surgery, a sex discordance between the surgeon and the patient was associated with poorer outcomes, particularly among female patients treated by male surgeons [9]—an observation that mandates further enquiry.

Of course, diversity is not just about gender, it is multi-dimensional. The example of AO Spine RECODE-DCM includes input from a diverse range of professional disciplines and cultures. Age I think is noteworthy, and perhaps easily overlooked in medicine. Scientific innovation is traditionally led by senior and/or experienced professionals; however, in the business world, commercial giants such as Google, Apple and Facebook were founded by 20-year-olds. Is innovation in healthcare, in spine surgery, so different?

The significant learning curve within medicine and science perhaps favors experience, but it too can entrench beliefs. Returning to Ed Catmull’s reflection on Pixar, “When it comes to creative inspiration, job titles and hierarchy are meaningless”.

Professor Shekar Kurpad shared his perspectives on this topic for our AO Spine RECODE-DCM Research Top Tips podcast series, including the steps he has taken within his department to create a culture of innovation. On a personal level, he summarized what he saw as the key attributes for a successful academic spine surgeon: humility and openness. On a system level, he described initiatives such as appraisals, mentoring and other strategies to bring together different teams and individuals from across workforce hierarchies.

I think there is much to draw from this. Spine surgery is a pressurized environment; the clinical workload and culture of training favors fast and confident decision-making (so called ‘System 1 thinking’). It therefore creates little opportunity or capacity to deliberate or reflect (‘System 2 thinking’). This will favor a continuation, rather than a challenge, to any status quo. As a training spine surgeon, I have greatly benefited from a dual academic and clinical training program, which has afforded me greater time to reflect—but this is not a luxury all will have.

So, how can spine surgeons address diversity?

The AO Foundation has created its own diversity, inclusion and mentorship task force, AO Access, to attract, include and promote a more diverse membership. In their podcast series, ‘AO Access to Success’, experts examine relevant pitfalls: for example, the unconscious biases that lead to prejudice and unequal opportunity; and the social determinants of health that give rise to inexcusable inequities in care and outcomes. Taking the Implicit Association Test is recommended for assessing one’s biases; and making time for self-reflection and burn-out avoidance is advocated for improving workplace success. During the AO Spine RECODE-DCM consensus process, it was surprising how few surgeons were aware of high-priority problems such as pain in DCM until those perspectives were brought to their attention by people with lived experience of the condition—reinforcing the value of multi-stakeholder input to accelerate innovations in patient care.

However, the starting point, of course, is accepting that lack of diversity is a problem. The brief perspectives above reflect my personal journey, from having an awareness but no personal motivation to drive change, to feeling a strong imperative to drive change. My examples may not have been enough to persuade you; often, a personal journey is needed.

I reflect on a recent discussion about actions to increase workplace diversity amongst training colleagues in Cambridge, UK (we are, as expected, ~95% male): it was interesting to observe how the immediate concern became whether such positive actions might trump meritocratic decisions and give rise to an unfair disadvantage at a job interview (employment is very topical in UK neurosurgery because of significant overtraining within the specialty). During this discussion, encouragingly, the benefits of diversity-increasing initiatives were not challenged, the insight being that it is the personal implications of such initiatives that may be the barrier to change. Speaking from the standpoint of a white male, I am not immune to this concern. However, instead, we can choose to open our eyes to the many ways in which a lack of diversity will limit our overall potential.

In short, I would argue that spine surgeons are natural innovators but that our current culture is not optimized to enable this efficiently. The evidence is mounting that in order to deliver great innovation we first need to create diversity. In spine surgery, this will require positive action. The success of AO Spine RECODE-DCM is one such example, but more must follow.

About the author

References and further reading:

- Cornwall GB, Davis A, Walsh WR, Mobbs RJ and Vaccaro A (2020) Innovation and New Technologies in Spine Surgery, Circa 2020: A Fifty-Year Review. Frontiers in Surgery 7:575318. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2020.575318

- Grodzinski B, Bestwick H, Bhatti F, Durham R, Khan M, Partha Sarathi CI, Teh JQ, Mowforth O and Davies B (2021) Research activity amongst DCM research priorities. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 163(6):1561-1568. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04767-6

- WINS White Paper Committee: Benzil DL, Abosch A, Germano I, Gilmer H, Maraire JN et al. (2008) The future of neurosurgery: a white paper on the recruitment and retention of women in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg 109(3):378–86.

- Women in Surgery (2020) https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/women-in-surgery/statistics/

- Post AF, Dai JB, Li AY, Maniya AY, Haider S, Sobotka S et al. (2019) Workforce Analysis of Spine Surgeons Involved with Neurological and Orthopedic Surgery Residency Training. World Neurosurgery 122:e147-55.

- Hiller KP, Boulos A, Tran MM and Cruz AI (2020) What Are the Rates and Trends of Women Authors in Three High-impact Orthopaedic Journals from 2006-2017? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 478(7):1553-60.

- Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ and Suleiman LI (2018) Women in Orthopaedic Surgery: Population Trends in Trainees and Practicing Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 5;100(17):e116.

- Garikipati S and Kambhampati U (2020) Leading the Fight Against the Pandemic: Does Gender ‘Really’ Matter? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3617953 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3617953

- Wallis CJD, Jerath A, Coburn N et al. (2021) Association of Surgeon-Patient Sex Concordance with Postoperative Outcomes. JAMA Surg. Published online December 08, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6339

Disclaimer

The articles included in the AO Spine Blog represent the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO Spine or AO Foundation.