VSP, 3D modeling and AR welcome the new era of personalized CMF surgery

BY DR DAVID SHAYE

Over the last decade, digital technologies have transformed the landscape of cranio-maxillofacial (CMF) surgery. From virtual surgical planning (VSP) and intraoperative navigation to 3D modeling and augmented reality (AR), these innovations are reshaping the way surgeons' approach complex cases. But beyond the buzzwords, what do these advances actually mean for patient care—and for us as surgeons?

As digital tools become more accessible and affordable, it’s crucial for CMF surgeons to receive structured training early in their careers. Exposure to these technologies demystifies their use and sparks curiosity about new applications. Integrating up-to-date use of technology including digital planning, customized implants, and intraoperative tools and more will now be included in the updated Management of Facial Trauma curriculum courses. Learn how to get better diagnostics and facial visualization, improve fracture reduction and implant positioning, as well as establish better diagnosis with the support of dynamic views in complex fractures.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Dr David Shaye discusses how digital technologies like VSP, 3D modeling, and AR are transforming CMF surgery.

- Key outcomes include more precise planning, reduced operative times, and improved patient trust and satisfaction.

- Surgeons benefit through enhanced preoperative visualization, personalized implants, and efficient intraoperative workflows.

- Ongoing challenges include cost, accessibility, and the need for specialized training; future integration and research remain active topics.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

Streamlining decision-making with digital tools before and during CMF surgery

One of the most significant advantages of a full digital workflow is the transformation of surgical decision-making, both before and during the treatment procedure . The integration of digital tools into CMF workflows is already showing tangible benefits: reduced operative times, fewer complications, and better functional and aesthetic results.

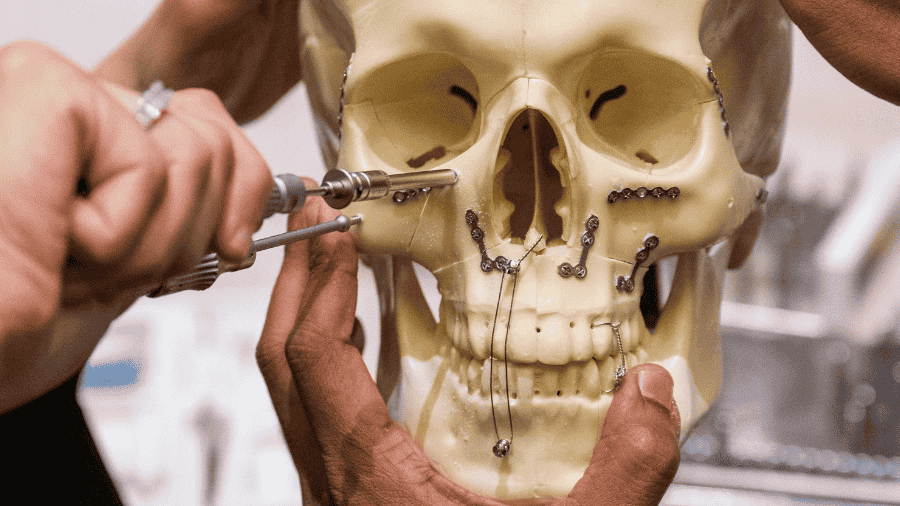

For example: in the retrospective case series by Singerman et al. (2025) on acute complex maxillofacial trauma using VSP services, they treated ten patients with severely comminuted injuries (including ~40% with orbital fractures) and used services like occlusal splints, 3D-printed patient models and pre-contoured plates.

While complications occurred in 7/10 patients due to the severity of the injuries, the authors emphasize that in such difficult cases, VSP allowed more predictable planning and execution (for instance: pre-bending plates on 3D-printed models rather than in the OR) (Singerman et al., 2025).

By minimizing guesswork and maximizing precision, these technologies allow for less invasive procedures and faster recoveries. For us surgeons, these models provide a tactile and visual understanding of each patient’s unique anatomy, allowing for meticulous planning and rehearsal.

During surgery, tasks that once consumed valuable time, such as bending plates to fit complex contours, can be offloaded to technology. With pre-bent, patient-specific implants ready to go, intraoperative workflow becomes more efficient and, in many cases, less invasive. This not only benefits the surgical team but also translates into shorter operative times and potentially faster patient recovery. But the benefits extend beyond the operating room.

Building patient trust through visualization with 3D CMF reconstructions

Patient trust is a cornerstone of successful surgical care, and ultimately, the goal of any surgical innovation is to improve patient outcomes. Digital tools, especially 3D reconstructions, have proven to be powerful aids in building that trust. A picture is worth a 1000 words, and a 3D reconstruction illustrates that concept.

When we bring patients into our offices and show them a 3D reconstruction of their own injury—rotating the model to view every angle—we’re not just educating them; we’re building trust. While patients trust their surgeon, they also trust their eyes, and technological tools help us educate patients in their own care.

For instance, the Singerman et al. (2025) paper describes a 34-year-old male with a self-inflicted gunshot wound involving a pan-facial fracture (mandible, maxilla, orbital walls). The VSP workflow produced a 3D printed model of ideal post-reduction anatomy and an occlusal splint, allowing the surgical team to plan meticulously—and then show the patient what “after repair” could look like.

Complex explanations suddenly become clear. Patients can see, in literal terms, why surgery is necessary and what it aims to achieve. This transparency often alleviates anxiety and empowers patients to participate actively in their own care.

Conceiving repairs before the first incision with VSP

Aristotle once said, “Art consists in the conception of the result to be produced before its realization in the material.” VSP embodies this philosophy, enabling surgeons to “conceive the repair” in a digital space before making a single incision. By virtually rehearsing the surgery, we can anticipate challenges, optimize our approach, and avoid unnecessary complications.

In the review by Rana et al. (2025), “Patient-Specific Solutions for Cranial, Midface, and Mandible Reconstruction”, the authors outline a full CAD/CAM workflow: from high-resolution imaging, segmentation, virtual resection/implant design, manufacturing of patient-specific implants (PSIs), through to postoperative outcome monitoring. They report that this workflow has resulted in greater surgical accuracy, improved aesthetic outcomes, and reduced operative times—albeit with caveats of cost, required expertise, and image quality dependency (Rana et al., 2025). By virtually rehearsing, you reduce intraoperative surprises.

Enhancing surgical practices and CMF education in the OR with AR

AR is rapidly emerging as a promising tool in both surgical practices and education. By superimposing digital information onto the surgeon’s field of view, AR offers a live feed of critical data during the procedure. This can highlight anatomical landmarks, alert the surgeon to vital steps, and even serve as a real-time teaching aid for trainees. The potential for AR in training younger surgeons is particularly exciting, as it offers a new dimension of experiential learning that is both interactive and immersive.

In the workflow described by Rana et al. (2025) AR or extended reality is positioned as a next frontier within CMF surgery. While there is still much to learn and explore with AR, we can still project the path: virtual planning + 3D printed guides + intraoperative navigation + AR overlay = tighter, smarter execution.

Technology as an extension—not a replacement—of surgical skill

It’s tempting to view these innovations as magic bullets , but technology remains just a tool. Rana et al. (2025) emphasize that although CAD/CAM workflows enable precise personalized implants, “modern technology complements rather than replaces the clinical expertise and principles established in cranio-maxillofacial surgery”.

As described by Singerman et al. (2025), despite the use of significant digital support in very complex trauma cases, complications still occurred (7/10 required return to OR). This reminds us that even with excellent tools, the patient, injury and context matter greatly.

Thus, while these tools refine our approach, they do not diminish the importance of clinical expertise and judgment. In reality, the best results occur when technology, knowledge, and traditional surgical skills work hand in hand.

A new tailored standard for precision and personalization

Perhaps the most profound change brought by these digital tools is the ability to deliver highly personalized, precise care. Just as a tailor crafts a suit to fit the contours of a client’s body, digital workflows enable us to “fit” our surgical interventions to the unique anatomy and injury pattern of each patient. This is a game-changer in, for example, orbital trauma, where millimeters matter for both function and aesthetics.

For instance, in the Singerman et al. (2025) trauma series, they used patient-specific 3D‐printed plates (in 4/10 patients) and 3D printed models (in 4/10) to assist with highly comminuted fractures. They highlighted that 3D models and custom plates were especially helpful when there was bone loss and complex fragment geometry.

In the Rana et al. (2025) review, the guidelines emphasize that different anatomical regions (cranial, midface, mandible) impose different demands on implant design, material and workflow—and that patient-specific solutions are increasingly the standard.

Another example is the Smolka et al. (2025) paper on proportional condylectomy using a titanium 3D-printed cutting guide (8 patients) for condylar hyperplasia. In that study, virtual mirroring of the healthy side allowed precise definition of how much bone to resect; intraoperative positioning of the guide and resection accordingly led to predictable outcomes.

Virtual surgical planning allows us to digitally reduce fractures, simulate repairs, and pre-bend plates or design patient-specific implants before stepping into the operating room. This level of preparation means that we’re not improvising solutions on the fly; instead, we’re executing a well-conceived plan tailored to the individual.

The result? More predictable outcomes, fewer surprises, and a higher degree of patient satisfaction. More precise surgery translates into less tissue trauma, which often leads to shorter recovery times, fewer complications, and better long-term functional and aesthetic results. The ability to plan and execute with such accuracy means that the guesswork is minimized, and the margin for error is significantly reduced.

The promises digital workflows hold for CMF surgery

Despite the promise of digital workflows, challenges remain. The high cost of new technologies can limit widespread adoption, and many regions around the world still lack access to basic surgical hardware, let alone advanced digital tools.

The paper by Rana et al. (2025) notes that while patient-specific workflows bring benefits, limitations include “high costs, the need for specialized expertise, and dependency on accurate imaging data”. In the Singerman et al. (2025) study, the authors also state that turnaround time for VSP/bespoke implants remains a limiting factor in acute trauma (in their series average 8.6 days to primary repair).

However, the digital transformation of CMF surgery is well underway. Just as the introduction of plates and screws once revolutionized trauma care, today’s digital technologies are poised to become the new standard. As costs decrease and accessibility improve, we can expect these tools to be integrated into routine practice. The journey is ongoing, but the direction is clear: a future where technology and surgical expertise work hand in hand for the benefit of every patient.

About the author:

References and further reading:

- Rana, M., Buchbinder, D., Aniceto, G. S., & Mast, G. (2025). Patient-Specific Solutions for Cranial, Midface, and Mandible Reconstruction Following Ablative Surgery: Expert Opinion and a Consensus on the Guidelines and Workflow. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 18(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18010015

- Singerman, K. W., Morisada, M. V., Kriet, J. D., Flynn, J. P., & Humphrey, C. D. (2025). Virtual Surgical Planning for Management of Acute Maxillofacial Trauma. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 18(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18010018

- Smolka, W., Cornelius, C.-P., Obermeier, K. T., Otto, S., & Liokatis, P. (2025). Proportional Condylectomy Using a Titanium 3D-Printed Cutting Guide in Patients with Condylar Hyperplasia. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 18(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18010007

You might also be interested in...

AO CMF Course—Management of Facial Trauma

This course provides learners with the fundamental knowledge and principles for the treatment of craniomaxillofacial fractures and their complications. It covers diagnostic and treatment principles for midface and mandibular fractures, as well as the prevention and treatment of complications.

AO CMF Course—Advanced Management of Facial Trauma

This 2.5-day hands-on course with human anatomical specimens covers complex facial fractures and posttraumatic deformities involving the entire facial skeleton. It focuses on the nasoorbitoethmoidal (NOE) region, including soft-tissue management.

AO CMF Education

AO CMF's courses and events, online learning tools, educational videos, fellowship opportunities and more—designed for craniomaxillofacial surgeons, residents and orthodontists, to enhance their surgical knowledge and skills.