MIS TLIF: Tips and tricks to improve lordosis and achieve solid fusion

BY DR AVELINO PARAJÓN AND DR ROGER HÄRTL

Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MIS TLIF) has become a well-established technique for the treatment of a wide spectrum of degenerative lumbar pathologies. Its advantages in terms of reduced muscle disruption, lower blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery are well documented. However, concerns persist regarding its ability to reliably restore sagittal alignment—particularly segmental lordosis—and to achieve fusion rates comparable to open techniques.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Parajón and Härtl explain how precise MIS TLIF technique improves lumbar lordosis and fusion across degenerative lumbar conditions.

- Positioning, full disc prep, anterior lordotic cages, controlled compression, and smart grafting drive alignment and fusion.

- Apply stepwise pearls to place cages anteriorly, maximize segmental correction, reduce pseudarthrosis, and match open TLIF fusion rates.

- The ongoing debate discusses rod contouring for single levels, cage technologies, and when ALIF is better for major deformity correction.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

In experienced hands, MIS TLIF is not merely a less invasive alternative, but a powerful to maintain or increase lumbar lordosis and achieve robust arthrodesis. The success of the procedure depends less on the approach itself and more on meticulous surgical technique: attention to positioning, disc preparation, implant selection, and biologic strategy. This article focuses on practical, experience-based technical pearls to optimize lordosis and fusion in MIS TLIF, while contextualizing these strategies within the current evidence.

Patient selection and preoperative planning

Appropriate patient selection remains the cornerstone of successful MIS TLIF. Ideal candidates include patients with low-grade spondylolisthesis, recurrent disc herniation with instability, foraminal stenosis, and segmental degenerative disc disease. While MIS TLIF can be extended to more complex deformities, expectations regarding sagittal correction must be realistic.=

Preoperative planning should include a thorough sagittal balance assessment. Standing full-length radiographs are essential to evaluate pelvic incidence, lumbar lordosis mismatch, and compensatory mechanisms. Identifying the contribution of the index level to overall lumbar lordosis helps define the surgical goal. Disc height, disc angle, and segmental mobility—assessed with dynamic radiographs—should guide cage selection and positioning strategy.

Computed tomography is particularly useful in revision cases or in patients with endplate sclerosis, where fusion biology may be compromised. In these scenarios, both mechanical and biologic strategies must be optimized to offset the limitations inherent to a minimally invasive approach.

Surgical exposure and facetectomy

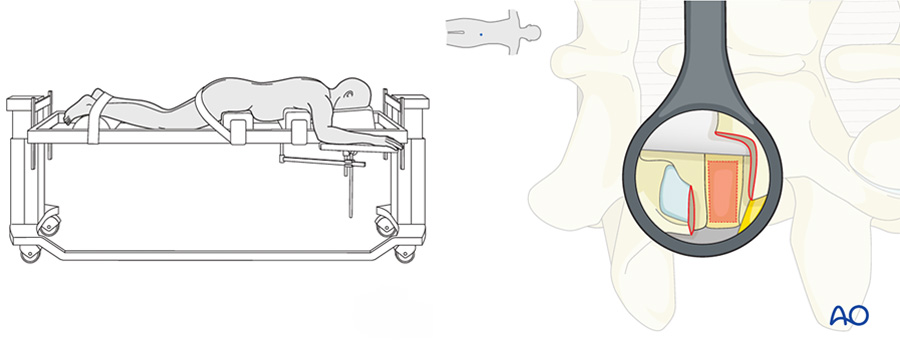

In MIS TLIF, the quality of decompression and release is directly related to the ability to restore lordosis. A complete unilateral facetectomy is often necessary, not only for neural decompression, but also to allow adequate distraction and cage insertion.

Partial facetectomy may obstruct access to the disc space, restrict cage positioning and limit cage size. A thorough release of the posterior elements on the working side facilitates segmental mobility and improves the effectiveness of subsequent compression maneuvers.

Contralateral indirect decompression is generally sufficient in most cases; however, if preoperative imaging suggests significant bilateral rigidity, additional release may be required to achieve meaningful sagittal correction. Bilateral facetectomy sometimes may require bilateral MIS approach.

Disc space preparation is the foundation of fusion

Disc preparation is arguably the most critical step for achieving solid fusion, and it is also one of the most technically demanding aspects of MIS TLIF. Limited visualization and working corridors increase the risk of incomplete disc removal and inadequate endplate preparation.

The goal is circumferential disc clearance while preserving subchondral bone. Sequential disc shavers, angled curettes, and pituitary rongeurs should be used systematically. Endplate violation must be avoided, as it compromises both mechanical support and fusion biology. Special care must be taken in elderly patients to avoid this.

Fluoroscopic guidance or intraoperative navigation helps confirm adequate anterior and contralateral disc preparation. Incomplete disc clearance remains a leading cause of pseudarthrosis in MIS techniques and cannot be compensated by biologics alone.

A thorough discectomy creates also bigger space to deliver more bone graft around the interbody cage; the amount of graft inside a TLIF cage is small.

Interbody cage selection and placement

Cage selection plays a pivotal role in both lordosis restoration and fusion. Lordotic cages, particularly those with 8–12 degrees of built-in angulation, can meaningfully contribute to segmental alignment when placed anteriorly.

Anterior cage positioning is critical. A cage placed too posteriorly functions primarily as a spacer rather than a lever for lordosis. Techniques such as sequential disc distraction, contralateral release, and careful trajectory planning facilitate anterior placement even through a unilateral MIS corridor. Banana cages are also a good option,

Cage height should restore disc space without overdistraction, which may increase the risk of subsidence and compromise endplate integrity. Expandable cages may offer advantages in selected cases, but they should not replace proper disc preparation and positioning principles. Expandable cages in lordosis, not only in heigh, can help to add lordosis. Cages that expand in lordosis can add around 4 degrees of segmental lordosis Porotic titanium cages probably can help to promote fusion better than PEEK cages.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Several pitfalls can undermine outcomes in MIS TLIF. Awareness and deliberate avoidance of these issues are hallmarks of experienced MIS surgeons:

- Inadequate positioning, resulting in lost opportunity for lordosis restoration

- Undersized or posteriorly placed cages, limiting sagittal correction

- Incomplete disc preparation, leading to pseudarthrosis

- Insufficient posterior compression, failing to capitalize on fixation mechanics

Postoperative considerations and follow-up

Early mobilization is generally encouraged, as MIS TLIF provides immediate segmental stability. The routine use of postoperative bracing remains controversial and should be individualized.

Radiographic follow-up should include standing lateral radiographs to assess maintenance of lordosis and CT imaging when fusion status is uncertain. Long-term outcomes correlate strongly with sagittal alignment maintenance and solid arthrodesis.

Conclusion

MIS TLIF, when performed with meticulous technique and thoughtful planning, is fully capable of restoring segmental lordosis and achieving solid fusion in experienced hands. The minimally invasive nature of the approach does not inherently limit outcomes; rather, it demands a higher level of technical precision.

Positioning, disc preparation, anterior cage placement, controlled compression, and sound fusion biology form the foundation of success. Current evidence, including meta-analytic data, supports the notion that fusion rates are comparable to open TLIF and across graft materials when these principles are respected.

Ultimately, MIS TLIF is not a shortcut. It is a refined technique where details matter, and mastery translates directly into durable clinical and radiographic results.

Anyway, if the main goal is to achieve significant lordosis like in multilevel deformity cases, flatback cases or sometimes at L5/S1 then thought should be given to ALIF instead of TLIF. For the majority of spondylolisthesis cases and degenerative disc disease TLIF is the preferred option.

About the authors:

Härtl also serves as the official neurosurgeon for the New York Giants Football Team. He received his MD from the Ludwig-Maximillians University in Munich, Germany, postdoctoral research fellow at Weill Cornell Medical College, fellowship in neurocritical care at Charite Hospital of the Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany, surgical internship and residency at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, neurosurgery residency at NY Presbyterian Weill Conrell Medical Center and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer center, specialized training in complex spine surgery at the Barrow’s Neurological Institute in Phoenix. Roger Härtl is the chair of the AO Spine MISS Task Force.

Further reading:

- Lener S, Wipplinger C, Hernandez RN, Hussain I, Kirnaz S, Navarro-Ramirez R, Schmidt FA, Kim E, Härtl R. Defining the MIS-TLIF: A Systematic Review of Techniques and Technologies Used by Surgeons Worldwide. Global Spine J. 2020 Apr;10(2 Suppl):151S–167S

- Jitpakdee K, Sommer F, Gouveia E, Mykolajtchuk C, Boadi B, Berger J, Hussain I, Härtl R. Expandable cages that expand both height and lordosis provide improved immediate effect on sagittal alignment and short-term clinical outcomes following minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MIS TLIF). J Spine Surg 2024 Mar 20;10(1):55–67

- Sommer F, Hussain I, Kirnaz S, Goldberg JL, Navarro-Ramirez R, McGrath LB Jr, Schmidt FA, Medary B, Gadjradj PS, Härtl R. Augmented Reality to Improve Surgical Workflow in Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion—A Feasibility Study With Case Series. Neurospine 2022 Sep;19(3):574–585

- Lian X, Navarro-Ramirez R, Berlin C, Jada A, Moriguchi Y, Zhang Q, Härtl R. Total 3D Airo® Navigation for Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:5027340

- Parajón A, Alimi M, Navarro-Ramirez R, Christos P, Torres-Campa JM, Moriguchi Y, Lang G, Härtl R. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Meta-analysis of the Fusion Rates. What is the Optimal Graft Material? Neurosurgery 2017 Dec 1;81(6):958–971

- Wu RH, Fraser JF, Härtl R. Minimal access versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: meta-analysis of fusion rates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010 Dec 15;35(26):2273–81

- Kartal A, Farooq M, Hamad MK, Bratescu R, Ikwuegbuenyi CA, Willet N, Boadi BI, Berger J, Hernández- Hernández A, Villanueva- Solorzano PL, Härtl R: Ten- step technique for navigated tubular transforaminal and extraforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Spine Surg 2025; 22(4): 1013–1028

You might also be interested in...

Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MISS)

AO Spine MISS educational material and courses cover all types of minimally invasive spine operations through tubular/microscopic, endoscopic, and instrumented procedures.

MISS Spectrum Series online course

This course covers the full spectrum of this ultimate tissue-preserving technique, from indications and general skills to specific microscopic, endoscopic, and instrumented procedures.

AO Surgery Reference resource

AO Surgery Reference is a resource for the management of spinal degeneration, trauma, deformities, and tumors, based on current clinical principles, practices and available evidence.

AO Spine Guest Blog: Degenerative Spine

The AO Spine Guest Blog highlights diverse views and perspectives from the spine community around the world. It supports our mission to share knowledge and improve patient care.