Cervical Subaxial Facet Injuries: evaluation, management, and how to use the AO Spine Classification System

BY DR RATKO YURAC AND DR ANDREI JOAQUIM

-

Read the quick summary:

- Ratko Yurac and Andrei Joaquim discuss the importance of paying attention to the Facet Fractures which have been described in the AO Spine Subaxial Classification system.

- Specific attention is being added to F2 and F3 injuries, where surgeons’ judgment remains key for safe treatment.

- Classification can standardize diagnosis but to avoid missed instability careful imaging interpretation is required.

- Ongoing questions include predicting treatment failure in borderline cases and improving diagnostic consistency for F2–F3 injuries.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

The AO Spine SCSICS is a powerful diagnostic tool that provides good guidance to spine surgeons, but judgement is always called for in finding the best treatment option for each patient. Here, we aim to give guidance and examples on how to use the classification.

Creating a common language using Classification Systems

Classifications help clinicians and surgeons speak a common language, to avoid misunderstandings and misinterpretation. Their value becomes evident in training and educational scenarios.

The AO Spine Subaxial Cervical Spine Injury Classification System is based on four major criteria:

- injury morphology (A, B and C),

- facet injury involvement (F1 to F4),

- neurological status (N0 to NX),

- case-specific modifiers (M1 to M4).

The Facet category was incorporated into the AO Spine SCSICS because, in the cervical spine, certain injury patterns are characterized primarily by damage to the facet joints. Often, there is no associated vertebral body fracture, or this injury is minor in appearance, and facet injuries are the main determinant of residual stability.

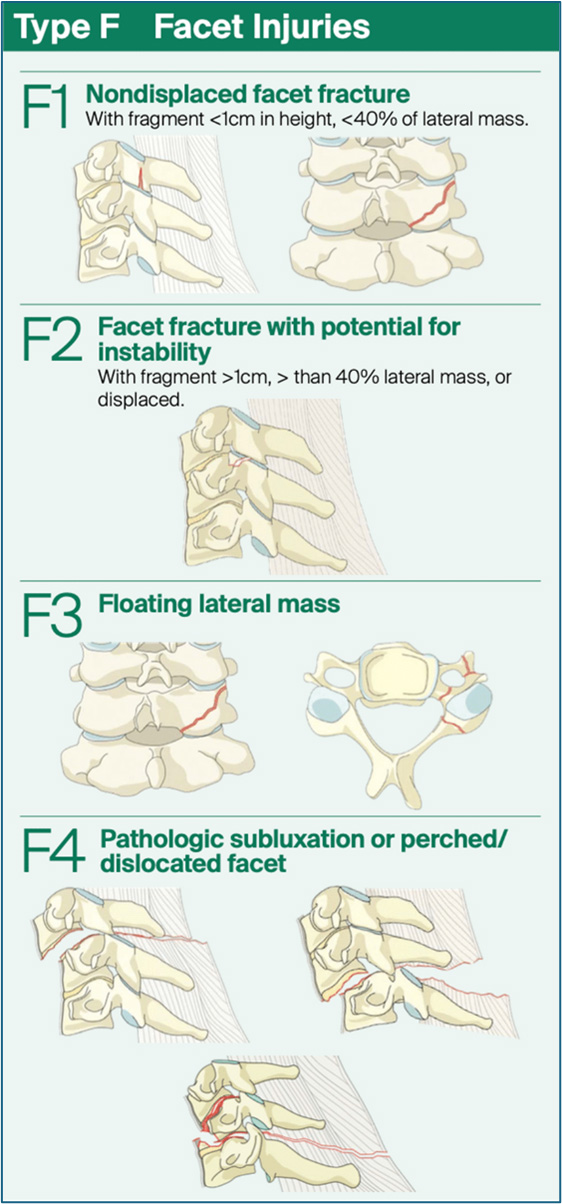

Four types of cervical facet injuries are described in the AO Spine SCSICS:

F1: Non-displaced fracture—fragments are smaller than 1 cm and comprise less than 40% of the lateral mass.

F2: Displaced fracture, potentially stable—fragments are either larger than 1 cm, comprise more than 40% of the lateral mass, or there are signs of displacement.

F3: Floating lateral mass, unstable—a disruption of the pedicle and lamina resulting in disconnection of superior and inferior articular processes at a given level or set of levels. This injury may result in the instability of two motion segments.

F4: Comminuted, highly unstable—includes any subluxation or dislocation, with or without an associated fracture.

If multiple injuries occur in the same facet, only the most severe injury is classified. If both facets on the same vertebra are injured, the right-sided facet injury is listed before the left-sided injury. The modifier "Bilateral" is used if both facets exhibit the same type of injury. When only facet injuries are identified (i.e., no A, B, or C injuries), they are listed first after the level of injury.

Figure 1. Graphic representation Type F facet category in AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System

The involvement of facet injuries, particularly for F2 and F3, requires the surgeons' special attention because they are not always adequately recognized. When not associated with clearly unstable injuries, they can be underestimated, especially in the case of isolated, non-displaced injuries.

Recommendations for cervical facet injuries management

Non-operative management is relatively well accepted for F1 morphologies while surgical treatment is recommended for F4 injuries. In general, surgical management is recommended for unstable injuries. F2 and F3 injuries are usually components of unstable B- or C-injuries, which dictate the surgical strategy.

Instability criteria and recommendations for cervical fractures based on the literature

These criteria have been described in the literature:

- Subluxation of a facet joint (less than 50% overlap)

- Fracture of a facet joint (more than 10 mm or 40% of the facet joint surface)

- Sagittal translation (more than 3.5 mm)

- Delta endplate angle more than 15º

The recommendation of spine section DGOU for F3 Injuries (Floating Lateral Mass) is the surgical resolution because they are generally unstable with B—or C-injuries. Possible nerve root compression by the facet fragment may, therefore, require an additional posterior approach in case of anterior stabilization. Because the underlying instability usually involves the cranial and caudal adjacent segments, these should be included in the stabilization.

A pragmatic proposal in isolated facet injuries: beyond classification

While not as common, isolated F2 and F3 facet injuries without type B or C injuries or clear instability require our attention and consideration. Significant deficiencies have been noted in diagnosis, instability assessment, treatment, and predicting the failure of conservative treatment. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of the injury's morphology, particularly the "floating mass" or F3, soft tissue integrity (disc and PLC), and dynamic instability is essential.

It is important to emphasize the use of the "M1 modifier (Posterior Capsuloligamentous Complex Injury without complete disruption)" of the AO Spine SCSICS when ligamentous integrity is uncertain. This modifier encourages further imaging or close follow-up rather than making binary decisions.

Any facet joint injuries (F1-F3) should warrant an MRI to identify a disco-ligamentous injury if there remains uncertainty regarding the need or extent of any surgical stabilization. Additionally, any other suspicion of a disco-ligamentous injury also necessitates an MRI.

To address the gap in evaluating subaxial cervical lesions within this clinical and radiological context, it is important to include:

- CT morphology: 1 mm or less slice thickness and 2-dimensional (2D) reconstructions in the 3 standard planes (sagittal, transverse, coronary) as minimum requirements, might be helpful in specific situations, in special for diagnosis F3 facet joint lesion.

- MRI evaluation of PLC and disc for M1 modifier or suspected disc injury.

- Consider deferred dynamic X-rays

- Symptom trajectory (pain, deficit, deformity)

- Risk context (bone quality, compliance)

Recent advancements in cervical facet injuries

Recently, some clinical studies were performed to highlight the importance of understanding cervical facet injuries:

Cirillo, Ricciardi et al. (2024): Systematic Risk Factors for Failure of Non-operative Management in Isolated Unilateral Non-displaced Facet Fractures of the Subaxial Cervical Spine: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. This study concluded that lateral floating mass cervical facet fractures (5.41 times higher odds) and larger fracture fragment size (measured either in absolute terms or as a percentage) are significant risk factors for failure of non-operative treatment.

Case snapshots: the invisible instability in F3 injuries

A healthy 18-year-old male, amateur rugby player, sustained cervical trauma during a match. While sprinting, he launched forward to tackle another player, impacting head-first against the opponent’s hip. He collapsed on the field with severe neck pain and was transferred urgently to a trauma center without cervical immobilization.

On arrival, the patient was standing, leaning rigidly against a wall, with intense neck contracture and a complete inability to mobilize the cervical spine. The neurological exam was intact (Glasgow 15). An emergency CT revealed a left-sided C6–C7 facet fracture with floating lateral mass morphology (AO-F3) without displacement. A rigid Miami J collar was placed immediately.

MRI showed significant edema of the left lamina and pedicle of C6, with increased joint effusion at the C6–C7 facet joint, anterolisthesis, a traumatic posterior disc protrusion (left-extruded) compressing the anterior dural margin, and inflammatory changes in paravertebral muscles. There was also facet fluid, subtle misalignment at C5–C6, and a high STIR signal in interspinous ligaments from C4 to C7. The spinal cord was intact, with there is no canal compromise.

Diagnosis: AO-F3 fracture of the left facet joint at C6–C7 with occult instability, confirmed by MRI.

Management: The patient underwent an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) at C6–C7 with anterior plating. The approach showed a complete rupture of the disc. The postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the symptoms resolved.

Cabrera, Yurac et al. (2021): Validation study on AO Spine SCSICS and its reliability. A survey consisting of 16 computed tomography (CT) scans of patients with cervical facet fractures. A total of 135 surgeons completed both surveys. The overall diagnostic accuracy of all responses was 65.4%. Inter-observer and intra-observer agreement rates for F1/F2/F3/F4 were 55.4%/47.6%/64.0%/94.7% and 60.0%/49.1%/58.0%/93.0%, respectively. There was significant variability in diagnostic accuracy for F1 through F3-type fractures, whereas almost universal agreement was achieved for F4-type injuries.

Joaquim, Yurac et al. (2020): Management of Unilateral Cervical Facet Joint Dislocation in Neurologically Intact Patients: Results of an AO Spine Latin American Survey. Survey with 197 respondents answering all the questions. Nonsurgical management was considered by 25% of the surgeons. The majority stated that magnetic resonance imaging is necessary (65%) to treat this type of patient. A posterior approach was preferred by 44%, an anterior approach by 29%, and a combined approach by 25%, while 2.2% did not answer.

Canseco et al. (2021): Regional and experiential differences in surgeon preference for the treatment of cervical facet injuries: a case study survey with the AO Spine Cervical Classification Validation Group. A survey was sent to 272 AO Spine members across all geographic regions with a variety of practice experiences. A total of 189 complete responses were received. Over 50% of responding surgeons in each region elected to initiate management of cervical facet dislocation injuries with an MRI, with 6 case exceptions. Overall, there was considerable agreement between American and European responders regarding the management of these injuries, with only 3 cases exhibiting a significant difference.

These publications highlight some inconsistencies in global practices regarding facet injuries and also stress the necessity for practical diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms tailored for settings with diverse resources.

Conclusion: how to bring classification into action

The AO Spine Cervical Subaxial Injury Classification System is a powerful diagnostic tool that provides good guidance to spine surgeons. However, clinical and contextual judgment is mandatory to avoid late instability or undertreatment, especially for F3 facet morphology. A careful radiological evaluation is necessary to properly classify these injuries and select the best treatment option.

We would like to acknowledge and thank the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Trauma & Infection group and all members of the AO Spine Latam Trauma Group for their support!

About the authors:

References and further reading:

- Vaccaro AR, Koerner JD, Radcliff KE, et al. AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Eur Spine J. 2016; 25(7):2173-2184. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-3831-3

- Urrutia J, Zamora T, Yurac R, et al. An independent inter-and intraobserver agreement evaluation of the AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(5):298-303. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001302

- Karamian BA, Schroeder GD, Lambrechts MJ, et al. AO Spine Subaxial Classification Group Members. An international validation of the AO spine subaxial injury classification system. Eur Spine J. 2023 Jan;32(1):46-54. doi: 10.1007/s00586-022-07467-6. Epub 2022 Nov 30. PMID: 36449081.

- Schnake, Klaus J. MD*; Schroeder, Gregory D. MD†; Vaccaro, Alexander R. MD, PhD, MBA†; Oner, Cumhur MD, PhD‡. AOSpine Classification Systems (Subaxial, Thoracolumbar). Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 31():p S14-S23, September 2017. | DOI: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000947

- White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1990:1

- Spector LR, Kim DH, Affonso J, Albert TJ, Hilibrand AS, Vaccaro AR. Use of computed tomography to predict failure of nonoperative treatment of unilateral facet fractures of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2827–2835.

- Schleicher P, Kobbe P, Kandziora F, et al. Treatment of Injuries to the Subaxial Cervical Spine: Recommendations of the Spine Section of the German Society for Orthopaedics and Trauma (DGOU). Global Spine J. 2018 Sep;8(2 Suppl):25S-33S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217745062. Epub 2018 Sep 7. PMID: 30210958; PMCID: PMC6130109.

- Cabrera JP, Yurac R, Guiroy A, et al. Accuracy and reliability of the AO Spine subaxial cervical spine classification system grading subaxial cervical facet injury morphology. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(6):1607–1614.

- Cirillo I, Ricciardi GA, Cabrera JP, et al. Risk factors for failure of non-operative management in isolated unilateral non-displaced facet fractures of the subaxial cervical spine. Glob Spine J. 2024; In press.

- Canseco JA, Schroeder GD, Patel PD, et al. Regional and experiential differences in surgeon preference for the treatment of cervical facet injuries: A case study survey with the AO Spine Cervical Classification Validation Group. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(10):2584–2592.

You might also be interested in...

AO Spine Classification Systems

AO Spine Injury Classification systems provide a comprehensive guide for patient care.

Knowledge Forum Trauma and Infection

The KF Trauma and Infection addresses the growing health care issue of spinal trauma.

AO Surgery Reference

Fracture management resource based on current clinical principles, practices, and available evidence.

Global Spine Congress

Meet leading researchers and clinical experts, and explore career development opportunities.