Single-position spine surgery: One position, a multitude of advantages

In recent years, the orthopedic community’s interest in single-position spine surgery has been steadily increasing, and for good reason. Dr. Raymond Hah and Dr. Ram Alluri discuss why this technique has become a mainstay of their practice and advise any surgeons aspiring to perform single-position spine surgery on how to get started.

As a primer, let’s clarify what we mean when we talk about single-position spine surgery. Spinal fusion surgeries typically involve interbody placement in either the supine or lateral decubitus position followed by adjustment of the patient into the prone position for instrumentation. However, with the single-position technique the patient remains in a lateral decubitus or prone position throughout the surgery. We initially explored the lateral single-position approach at USC as it is an elegant procedure that overcomes various issues associated with other approaches. Of note, single-position approaches have been described using various terminologies including oblique lumbar inter-body fusion, extreme lateral interbody fusion, and direct lateral interbody fusion.

Single-position surgery solves inefficiencies and shortens time in theatre

In general, there are several advantages to single-position surgery but the major driver that pushed us to start exploring the technique was deformity correction operations.

As a deformity surgeon the rule is, if you're not thinking about deformity, you're probably creating it. In that sense, the single-position approach provides a great solution in terms of patient safety and efficiency, this is from both a short- and a long-term perspective when considering alignment needs and adjacent pathology. For those operations where multiple interspaces are treated it is particularly advantageous not to have to flip the patient. Take an L5-S1 anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) for example, where the patient needs to be turned laterally for additional work. The days where we would perform a big abdominal incision to get L2-S1 anteriorly are long gone due to the high morbidity risk for the patient, so ultimately it was in exploring ways to solve that inefficiency that we began to look at single-position surgery.

A major advantage of the single-position technique is that you save time in theatre. If you work on a case where the position changes, you wait a long time for turnover and then if you add a flip in there, it can be equivalent to three cases, which makes for a long day at a big university. Using the single-position technique, you are able to treat a 5-1 disc in the lateral position with the lateral ALIF, then work up the lateral aspect of the spine and do multi-level laterals and avoid an additional flip. Single-position surgery has changed our ability to finish a deformity case in a day, as opposed to having to stage it and bring patients back the next day which is why we’re very passionate about the technique.

A recent study completed by the orthopedic team at New York University backs up our experience1. The study reported that with a traditional lateral position and instrumentation in the prone position, it takes an additional two hours to flip the patient. Two hours is effectively an additional case. Therefore, if you can do the surgery in one position, you're able to treat more patients. If you add that up over the course of a year, it's significant.

Additional benefits from deformity to degeneration cases

With single-position surgery, it's not only the elimination of the position change that saves time. A key time saver comes from being able to work concomitantly with your team and other specialists, instead of having them wait around for repositioning. For example, when working alongside a vascular team, it’s possible to begin some of the lateral work while they're doing their anterior exposure.

If we're flipping for screws, it’s possible to instrument L3-1, L2-S1 in the lateral position if there's no need for osteotomies. The orthopedic surgeon can therefore be cannulating pedicles while the vascular surgeon works on the anterior. Once the vascular surgeon is finished, we are able to complete the anterior work and then proceed to do the laterals as well. In our experience, most of the time savings arise when the vascular surgeon is closing an anterior incision. With regards to the orthopedic team, you can have someone performing the retroperitoneal access while you have your fellow or co-surgeon on the other side of the table actively decompressing, or you can have them actively putting in screws while you're putting in the cage.

We track outcomes closely at our center and have observed additional advantages to using the single-position approach. Our experience, backed by data from the literature, shows us that single-position surgery results in a valuable decrease in anesthesia time, less postoperative issues, earlier postoperative recovery, and a shorter length of stay for the patient2. Another aspect to consider is that with any position change you’re increasing the chance of sterility problems and consequentially the potential for increased infection.

Therefore, from a patient perspective, single-position surgery really makes sense. At our center we perform a lot of minimally invasive (MIS) transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions (TLIF). It's unusual to send a MIS TLIF patient home in less than 24 hours. With ALIFs, often two-level or even one-level ALIFs are in the hospital three or four days due to ileus and retroperitoneal swelling. Patients undergoing a one level lateral fusion with single-position screws routinely go home within 24 hours.

Following our successful experience with deformity correction, we expanded our use of the single-position technique to degenerative cases. In this setting, a real benefit of the single-position technique has been a reduction in repeated TLIFs and the need to take care of patients posteriorly.

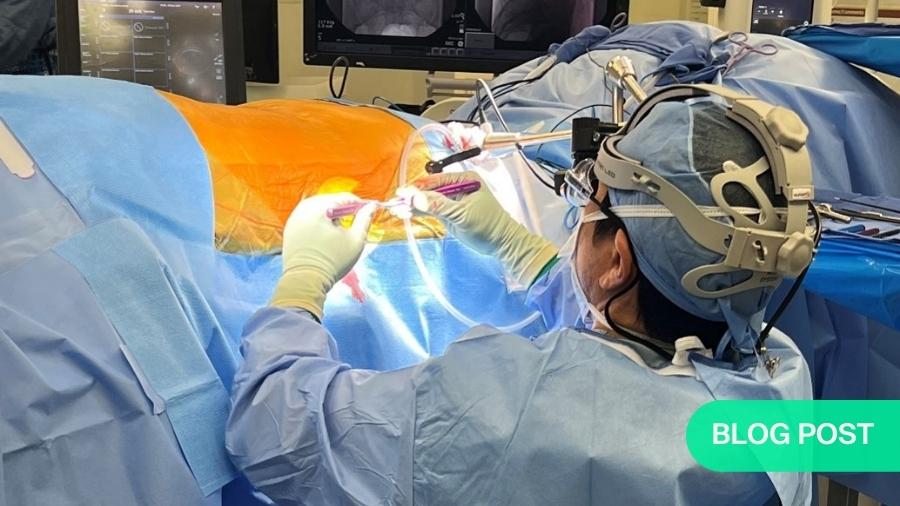

Thanks to fluoroscopic guidance and the use of navigation techniques, we are able to safely and reproducibly put screws into the lateral position. This has been a game changer because without that, there is a high threshold to work laterally and then flip to do the work in the back; it’s common to hear surgeons say that perhaps it’s better to rather go ahead with a TLIF instead. However, when you get to the point where you believe the indirect decompression is powerful and real if carefully selected and that you can do this in a single position, it really changes the way that you view clinical problems.

Prone lateral or lateral single-position technique?

In terms of learning the technique, a single-position operation may initially appear more daunting than more traditional approaches, especially when first starting out. However, based on all the points we have discussed and particularly from a safety standpoint it's better for the patient. Both the prone lateral and lateral single-position approaches come with their own learning curves.

In terms of the access, it's pretty similar in the lateral and prone lateral position but it's just that you're working at a deeper length. With the lateral approach, the vascular surgeons have to relearn how to do an ALIF in a lateral position and you as the spine surgeon have to learn how to put screws in the lateral position because you're used to having the patients prone. In particular, it’s more challenging to do an L4-5 lateral interbody fusion, as opposed to a L4-S1 ALIF.

The advantage of the prone lateral approach is that we all work in the prone position, which makes things more familiar. Putting screws in prone is easy so there's not much of a learning curve in terms of instrumentation. The learning curve is the retroperitoneal access which is challenging. This is firstly because the skin doesn't fall away as it does in the lateral position, so your blade length is 20-30 centimeters longer on average than in the lateral position and you're working in a much deeper corridor making visualization a little difficult. Secondly, the working angle is challenging; it's very ergonomically unfriendly to be working with the mallet and doing disk preparation essentially straight on. You have to rotate the bed 30 degrees, but then you're working orthogonally which means you have to be careful that you're not going too far posterior and entering the canal or too far anteriorly and accidentally releasing the anterior longitudinal ligament.

The other thing to be aware of in the prone lateral position is that you extend the hips3. This means the femoral nerve is more posterior. As a result, you think that you have more anterior access but actually you may not, because the femoral nerves are under more tension and can become stretched. We have observed anecdotally that the nerve doesn’t tolerate as much retraction time in the prone position as it does in the lateral position, especially with extended hips.

These are therefore some additional considerations when working in the prone lateral position. However, in technical terms the advantages are similar to the lateral position; there’s no flip, you can directly decompress in a position that you're used to and you can work simultaneously with other surgeons. One clear advantage of single-position lateral over prone is when doing the ALIF at L5-S1 you can get in a bigger cage. If you're doing a prone lateral and you're trying to go to L5-S1, you're basically limited to a TLIF. Therefore, you may not get the lordosis, the indirect decompression or the big cage and better biomechanical properties, but the decision ultimately comes down to the individual preference of the surgeon.

In terms of deciding to learn the prone lateral or lateral single-position technique, they both have their inherent advantages. If you want to harness the positioning lordosis or do osteotomies, it's nice to be able to do a prone lateral surgery, but for other clinical situations, it may be better to do a lateral single-position. Ideally you could learn both techniques, but single-position whatever way you do it is the way to go in terms of economic resources and efficiency.

How to get started with single-position surgery

When it comes to performing single-position surgery, our advice would be that any initial considerations should focus on the specific details of the case rather than any technical aspects. It is key to look firstly at the individual patient and at their anatomy beyond the spine. For example, examine the iliac crest and the vascular anatomy and ask is this approach favorable for this patient and have all the peripheral issues been considered? Once that is covered the technical aspects come into play.

For someone wanting to expand their skillset and learn how to perform the single-position technique, we believe the best way to move forward is by taking suitable cases and talking them through with somebody who has experience. There are a number of companies that can facilitate this. You can also go to a cadaver laboratory with an expert surgeon and work on the technique, have them teach it to you and review the indications with someone who's done hundreds of these surgeries. Finally, it is possible to attend courses that provide training on this topic.

In closing, the adoption of new techniques is always going to result in some controversy. However, we see significant advantages offered by single-position surgery, including clear safety benefits for the patient: Could it be time for you to explore single-position surgery in your center?

About the authors:

Raymond Hah, M.D. is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Dr. Hah specializes in the management of patients with neck and back disorders. He has a special interest in minimally invasive surgery.

Dr. Hah believes in educating patients so they are equipped to make the best decisions regarding their health. He has found that a multi-disciplinary and a multi-modal approach to treatment offers the best chance of sustained success. If surgery is necessary, he is committed to offering the most cutting-edge technology and technique to maximize the patient's experience and results.

Dr. Hah is actively engaged in clinical research to improve the care of patients with spinal disorders. He also teaches medial students, residents, and fellows at Keck Medical Center of USC.

R. Kiran Alluri, MD is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of The University of Southern California (USC) and a part of the USC Spine Center. Dr. Alluri specializes in the surgical treatment of all neck and back disorders. He has a special interest in cervical spine surgery, minimally invasive spine surgery and robotic technology. He also treats patients with adult spinal deformity and patients requiring complex revision surgery.

Dr. Alluri believes his most important role as a physician is to educate patients and their families about their condition and thoroughly explain treatment options so they can make an informed choice. His emphasis is always towards nonoperative management, utilizing a multi-disciplinary and multi-modal approach. In patients that require surgery, Dr. Alluri is trained in the latest minimally invasive and robotic techniques to expedite the recovery process and maximize postoperative function.

In addition to patient care, Dr. Alluri is actively involved in research with an emphasis on analyzing clinical outcomes and navigation technology. To date he has published over 80 peer-reviewed research articles and his work has been presented at over 130 research meetings.

References:

- Buckland AJ, Ashayeri K, Leon C, et al. Single position circumferential fusion improves operative efficiency, reduces complications and length of stay compared with traditional circumferential fusion. Spine J. 2021 May;21(5): 810-820.

- Mills ES, Treloar J, Idowu O, et al. Single-position lumbar fusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2022 Mar;22(3):429-443.

- Alluri R, Clark N, Sheha E, et al. Location of the Femoral Nerve in the Lateral Decubitus Versus Prone Position. Global Spine J. 2021 Oct; 21925682211049170 (Online ahead of print).

Disclaimer

The articles included in the AO Spine Blog represent the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO Spine or AO Foundation.