No, this is not another gender debate: Why gender-specific data is important in spinal surgery—and why we can no longer ignore it

BY DR SONJA HAECKEL

As surgeons, we would like to believe that we treat all patients equally: systematically, objectively and based on the best available evidence. But the more time I spend looking at the data, the harder it becomes to pretend that men and women navigate through our healthcare system in the same way. They don't. They never have. And the consequences are greater than many of us realize.

This imbalance begins long before a patient arrives at a spine outpatient clinic. It begins with the interpretation of symptoms, the structuring of treatment pathways and even the way we have built up our scientific knowledge over the last few decades. When you put all these pieces together, a picture emerges that cannot be ignored: sex matters. Not in a marginal, ‘interesting observation’ way, but in a profound, clinically relevant way, from the perspective of diagnosis, treatments, complication profiles, implant performance, and long-term outcomes.

We often talk about precision medicine as the future of healthcare. However, before we delve into genomics, proteomics or AI-driven applications, we need to address a far more fundamental variable—one that we currently undervalue and occasionally even ignore: biological sex and gender.

Let me explain why this is important with a few examples that should give us all pause for thought.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Dr. Sonja Haeckel discusses the critical impact of gender-specific data in spinal surgery and the systemic biases affecting patient care.

- Ignoring sex differences leads to clinical and research gaps, affecting diagnosis, treatment, and implant outcomes for women.

- Surgeons can improve care by integrating gender-specific data into research, device testing, and clinical decision-making.

- Ongoing discussion focuses on updating research standards, training, and addressing open questions about sex-based differences in outcomes.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

Same symptoms, different treatments: The silent bias in clinical decisions

I began looking into this topic because I was invited to this year's European Society for Biomaterials (ESB) conference in Turin to give a talk on gender differences in biomaterials. Well... this was something new for me, and to be honest, I had to start my presentation from scratch. While working on the talk, I came across one of the most striking findings that emerged early on in my research on this topic: a study showing that orthopaedic surgeons are 22 times more likely to recommend total knee replacement to male patients than to female patients with the same symptoms, X-ray images and functional limitations.

Not 22%. Twenty-two times!

This is not a typo, and unfortunately, it is not an isolated case. In many specialties, women's symptoms are more often interpreted as ‘psychosocial,’ while men's are labelled ‘organic.’ Men receive more interventional treatments, women more analgesics. Even in emergencies such as myocardial infarction, women are less likely to receive the interventions recommended in the guidelines because their symptoms do not match the ‘classic’ description for men.

In spinal surgery, we encounter more subtle variations of this pattern. Women with degenerative diseases often have advanced symptoms and poorer preoperative scores, yet their postoperative outcomes are just as good as those of men. This means that many women simply undergo surgery later. Not because their condition is milder, but because over time, somewhere between radiology, primary care and surgical triage, they are interpreted differently.

Clinical bias is rarely intentional. Most of us would strongly reject the idea that we ‘treat the sexes differently’. However, data from large cohorts clearly show that we do. Awareness is the first step, correction the second.

If our daily decisions unconsciously diverge according to gender, this applies even more to the scientific evidence base.

Of more than 20,000 clinical trials involving over five million participants, only 25% of the enrolled subjects were women. And only 14% of the trials included a sex-specific analysis. In many fields, such as cardiology, oncology and immunology, the representation of women is disproportionate to the actual burden of disease. The situation is no better in spinal research. When my team reviewed over 5,000 studies on thoracic and lumbar fractures last year, we found only a handful of studies that reported gender-specific results.

We cannot treat these conditions effectively if we do not study the populations affected by them effectively.

The reasons for this are historical and, in most cases, outdated: concerns about hormonal fluctuations, which have been disproved; exclusions due to pregnancy, which were applied generally without much thought; and the long-standing assumption that male physiology is the “standard” and female physiology is a “variant”. Well into the 20th century, the idea persisted that women complicate the data, while men simplify it.

However, this asymmetry has real clinical consequences. Women respond more strongly to the toxicity of cancer immunotherapy. They metabolize common drugs differently. And in surgery—our field of expertise—differences in anatomy, muscle composition, joint laxity, vascular fragility and bone density are not minor details. These are essential characteristics that influence outcomes.

If our evidence base is disproportionately based on male data, these imbalances are also reflected in our guidelines, indications, device designs and risk assessments.

Biology is not uniform: Bones, anatomy and biomaterials behave differently depending on gender

There is a critical interface for spinal implants: bone. And bone is not the same in men and women, at least after a certain age. From menopause onwards, women suffer from faster bone loss, which exceeds the decline in men over decades. Even before osteoporosis is formally diagnosed, subtle structural differences influence the pull-out strength of screws, the risk of cage subsidence and the potential for fusion.

Nevertheless, most biomaterial tests are still performed using data from male bones, male animals or cell lines where sex is not specified at all. In studies of cartilage and intervertebral discs, for example, up to 60% of in vitro studies do not specify the sex of the cells. This is equivalent to publishing a clinical study without specifying the sex of the participants—something no reviewer would accept.

In our field, there is growing recognition of the importance of load distribution, anchoring strategies and implant biomechanics in older people. However, if women have a different failure pattern—not because their pathology is different, but because their bone structure is different—we need to incorporate this into implant design. ‘One size fits all’ has never been true in orthopaedics, and it is becoming increasingly untenable in biomaterials for the spine.

Developing devices that work equally well for both sexes does not require two separate implant lines. It is necessary to test constructs in sex-balanced models, specify sex in all experiments, and integrate bone quality as a biological variable rather than a confounding factor.

Where we go from here: towards more accurate, equitable and data-driven spinal care

The good news is that things are finally changing: the NIH now requires gender to be considered in all research projects it funds; the 2024 Declaration of Helsinki explicitly addresses gender and sex differences; several European medical schools have established professorships in gender medicine; and journals are tightening their requirements for reporting sex.

But regulations only take us part of the way. The rest is up to us—surgeons, researchers, reviewers, educators, and industry partners—who shape the culture and daily practice of our field.

The necessary changes are not revolutionary, but rather practical in nature:

- Specifying gender in every study, from cells to clinical cohorts.

- Stratifying results when sample size allows.

- Recruiting balanced populations that are representative of actual disease patterns.

- Testing biomaterials and implants in gender-diverse models.

- Check whether there are already studies in your field that look at this difference, do a scoping review with your research team and see if there are any gender-specific differences (low hanging fruits to get a paper published).

- Offer trainees training on gender-specific anatomy, biomechanics and risk profiles.

- And above all: constantly question your own assumptions.

Surgery is an evidence-based profession, but evidence only emerges when we look for what is missing. And currently, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding of how biological sex influences everything from the interpretation of symptoms to the integration of implants.

This is not a niche topic. It is a question of quality of care.

Recognizing gender differences not as complications but as essential data will lead to more accurate research, better surgical decisions, improved implant performance, and more representative patient outcomes.

You might also be interested in...

AO Access

A visionary initiative for the organization’s commitment to becoming a diverse and inclusive organization with equal access and opportunity for all.

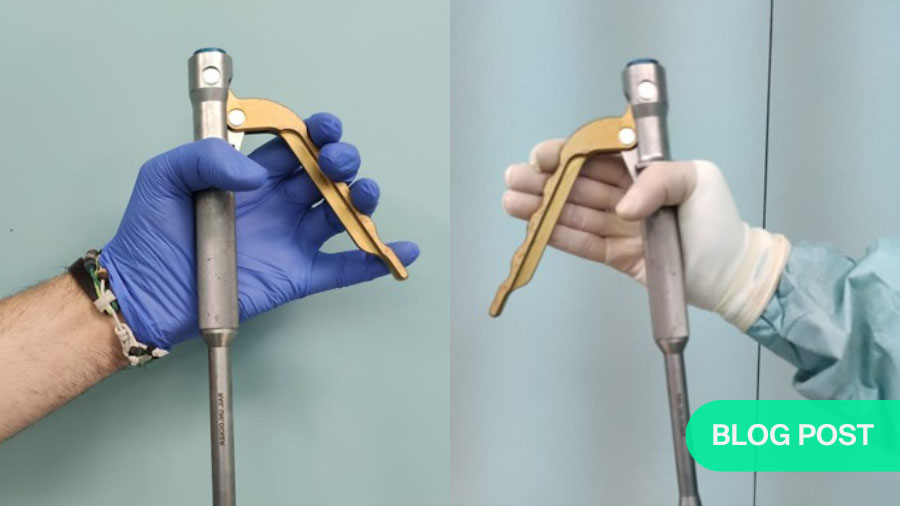

Ergonomic Surgical Tools

Many instruments are designed for the “average” surgeon, despite wide diversity in hand size and ergonomics among operating surgeons.

Global Spine Journal

AO Spine’s official scientific journal is an open access, peer-reviewed journal focusing on the study and treatment of spinal disorders.