Revision surgery with refixation after mandibular fractures—what precautions should be taken?

BY DR CLAUDIUS STEFFEN AND DR JAN VOSS

Revision surgery with refixation may be necessary in cases of osseous non-unions or osteomyelitis following mandibular fractures. Patients requiring such procedures often share similar background characteristics. In this article, Claudius Steffen and Jan Voss from Berlin examine these commonalities and highlight the quality of initial treatment as a critical factor in postoperative outcomes [1].

This guest blog article reflects one of the most cited articles in the Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction journal:

Steffen, C., Welter, M., Fischer, H., Goedecke, M., Doll, C., Koerdt, S., Kreutzer, K., Heiland, M., Rendenbach, C., & Voss, J. O. (2024). Revision Surgery with Refixation After Mandibular Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(3), 214-224.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Refixation is a serious but rare complication, but its consequences are significant: secondary surgeries are generally more complex than initial procedures.

- The authors’ findings emphasise the importance of high-quality surgical care.

- All refixation procedures included in the study were associated with fractures in the mandibular body, paramedian, or angle regions—fractures in the condylar or ramus areas did not result in severe complications.

- The most common complications requiring refixation involved osteomyelitis or non-union.

- To mitigate risks, patients with known compliance issues or significant risk factors should receive intensified management, with load-bearing fixation methods being an appropriate choice.

- Proper management of "pencil-bone" fractures and addressing non-restorable teeth is crucial.

- Determining the optimal treatment for mandibular fractures is not always straightforward, and consensus among specialists is limited.

- The authors call for improved clarity in treatment guidelines plus revisions to the current AO CMF classification system and guidelines.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

How common is refixation surgery after mandibular fracture treatment?

While refixation is a serious complication, it is fortunately rare. General complication rates after mandibular fractures range from 6–22%, but the need for refixation remains low. For instance, Scolozzi et al. reported a 3% refixation rate among 63 patients [2]. In our study, only 17 of 630 patients (2.7%) required secondary surgery. A major concern is delayed presentation—patients often return only after complications like osteomyelitis or abscesses have developed. Despite the low incidence, the consequences of refixation are significant. Revision procedures often require extraoral plating, which increases the risk of nerve injury and typically necessitates extended antibiotic treatment. These secondary surgeries are generally more complex than the initial procedures.

What are the risk factors for refixation?

Known risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, drug abuse, and immunosuppression. In our cohort, 64.7% of patients needing refixation had at least one of these factors. However, 35.3% had none—prompting a deeper evaluation. Among these, several patients were found to have received substandard surgical care. To assess this, we reviewed the 17 cases as part of a larger, blinded study using AO surgical principles. In 5 of the 6 patients without recognized risk factors, surgical quality was deemed inadequate—with full agreement among specialists in 3 cases. Our findings underscore not only the relevance of established risk factors but also the critical role of high-quality surgical care in preventing complications.

Were there any other notable findings in the patient group?

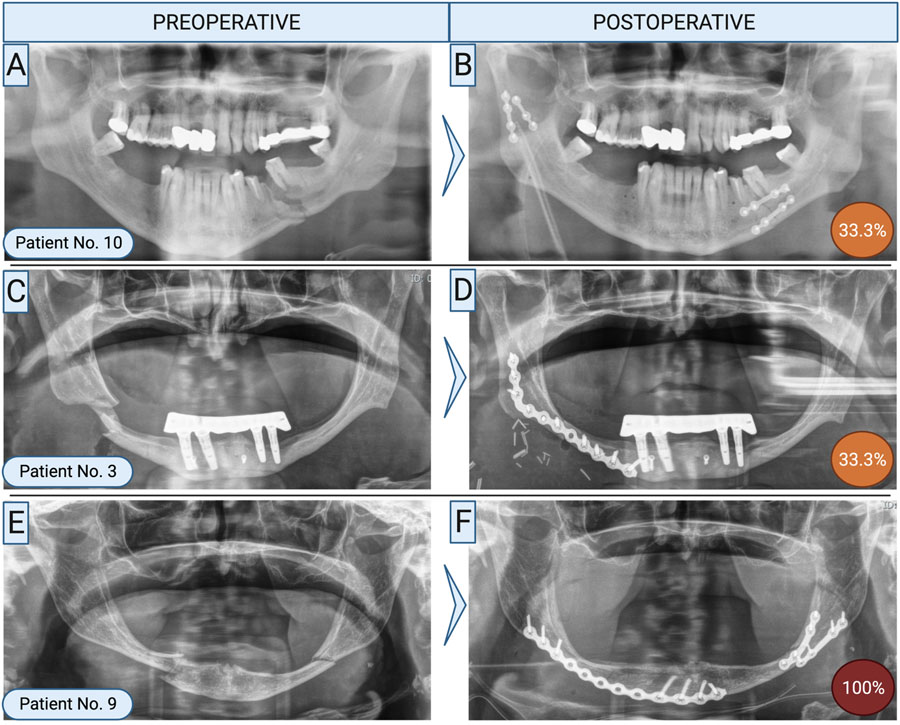

Yes. All refixation procedures (100%) were associated with fractures in the mandibular body, paramedian, or angle regions. Notably, fractures in the condylar or ramus areas did not result in complications severe enough to require refixation. Furthermore, whether patients sustained isolated or multiple fractures had no apparent influence on the likelihood of requiring secondary surgery.

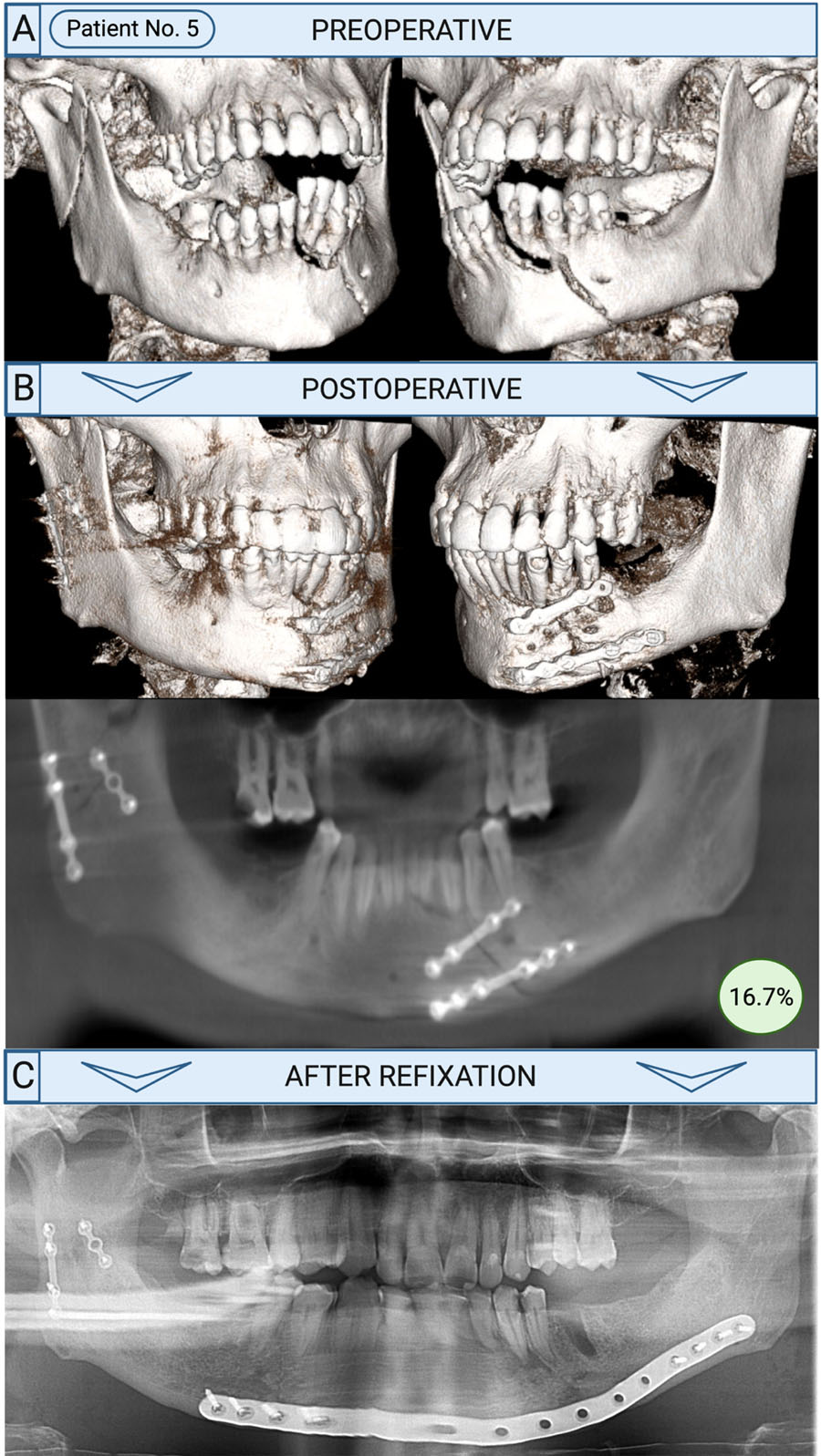

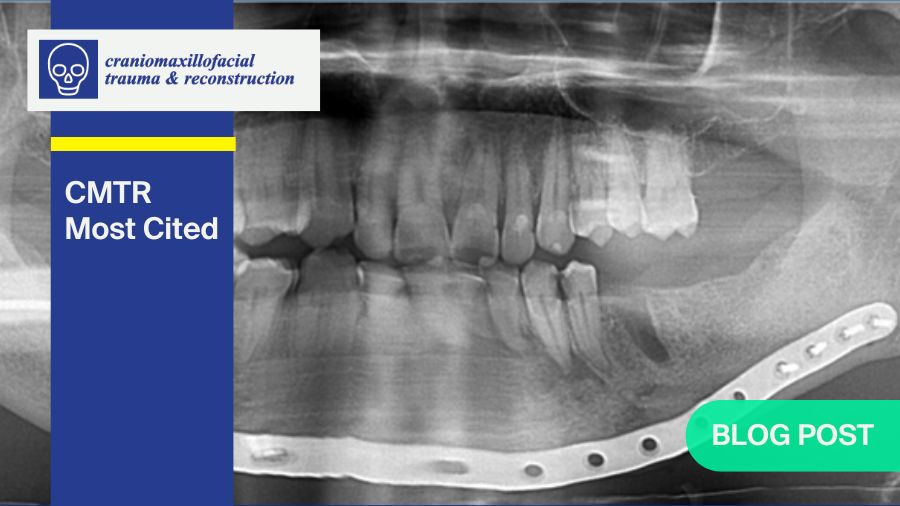

How was refixation performed?

Refixation was typically prompted by complications such as osteomyelitis or non-union, both of which demanded more invasive surgical approaches. In 82% of cases, an extraoral approach was used, employing load-bearing osteosynthesis techniques. Reconstruction plates were the most common fixation method—47% involved conventional plates, while 41% utilized patient-specific, 3D-printed plates.

Bone grafting from the iliac crest was necessary in about 30% of cases. Intraoral soft tissue conditions likely played a role in the surgical decision-making process, as successful grafting depends heavily on infection-free closure and adequate healing.

On average, refixation was performed 3.5 months after the initial surgery, ranging from 1 to 9 months—consistent with typical bone healing timelines. Patients who could be managed with hardware removal alone were excluded from this study. In some cases, intraoperative evaluation during revision may have revealed sufficient bone healing, negating the need for full refixation. Therefore, refixation was reserved for cases with substantial complications and inadequate osseous healing.

How can refixation be avoided as a surgeon?

While this study highlights several contributing factors, completely preventing the need for refixation remains challenging. Patients with substance use—particularly nicotine, alcohol, and drug abuse—often exhibit poor compliance, which increases complication risks. Issues may include delayed presentation, already-infected fractures, premature discharge, or failure to complete antibiotic regimens. Poor adherence to dietary restrictions and oral hygiene instructions, especially in the absence of consistent follow-up, further complicates recovery.

To mitigate these risks, patients with known compliance issues or significant risk factors should receive intensified management. This includes clearer communication, thorough counseling, and structured postoperative support. From a surgical standpoint, the choice of osteosynthesis should be tailored accordingly. For patients with anticipated compliance difficulties, load-bearing fixation methods may be more appropriate. Similarly, if intraoperative assessment reveals insufficient bone support, the use of mechanically stable plating is strongly recommended.

Beyond individualized care, the study underscores the critical role of surgical quality. Adhering to essential principles—such as proper management of "pencil-bone" fractures and addressing non-restorable teeth—is crucial. Our findings clearly demonstrate that deviations from these principles can lead to avoidable complications.

What are the weaknesses in current treatment guidelines?

One notable limitation highlighted in our study is the low interrater reliability (κ = 0.239), which falls into the “fair” range according to Landis and Koch [3]. This suggests that determining the optimal treatment for mandibular fractures is not always straightforward, and consensus among specialists is limited.

Improved clarity in treatment guidelines would be especially valuable for the future integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in clinical decision-making. AI could potentially analyze radiographic and clinical data to recommend specific treatments based on individual fracture patterns and patient characteristics.

Additionally, the current AO CMF classification system has its shortcomings. Not all fracture patterns fit neatly into its framework, leading to subjective interpretations and variable treatment approaches. The AO guidelines also lack recommendations on important technical aspects such as fracture reduction quality, plate adaptation, plate length, or optimal screw placement relative to the fracture line. Incorporating clinical parameters—such as the feasibility and duration of intermaxillary fixation—into future guidelines could further enhance consistency and outcomes in mandibular fracture management.

Do you have an interesting paper to publish?

Submit your paper to CMTR now!

A special call for manuscripts for CMTR's special issue on "Innovation in Oral- and Cranio-Maxillofacial Reconstruction" is open. Submit by October 31, 2025.

About the authors:

References and further reading:

- Steffen C, Welter M, Fischer H, Goedecke M, Doll C, Koerdt S, et al. Revision Surgery With Refixation After Mandibular Fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024;17(3):214-24.

- Scolozzi P, Richter M. Treatment of severe mandibular fractures using AO reconstruction plates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(4):458-61.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-74.

You might also be interested in...

CMTR Journal

Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction (CMTR) is the official scientific publication of AO CMF.

Facial Trauma

Learn state-of-the-art techniques and elevate your management of facial trauma and associated complications.

FACE AHEAD

The event where the top names in the CMF field reveal their best kept secrets and give hands-on advice to the next generation of surgeons.

AO Surgery Reference

Get the low-down on all aspects of the mandible: examinations, anatomy, terminology, literature, and special considerations.