Salvage procedures in cleft palate: managing alveolar oronasal fistulae

BY DR TING-CHEN LU

Cleft palate is a common congenital facial anomaly and there are many different palatoplasty techniques described for the repair of cleft palate. However, development of oronasal fistulae after palatoplasty remains a burden for surgeons.

As part of the AO CMF Global Study Club, Dr Ting-Chen Lu, Assistant Professor at the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, led an avid discussion about managing oronasal fistulae. With input from her co-presenters Dr Pramila Shakya, Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon at the Nepal Cleft and Burn Centre in Kirtipur Hospital, and Dr Juna Gurung, Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon at the B&B Hospital in Nepal, Dr Lu takes a look at salvage procedures of the cleft palate in particularly difficult pediatric cases.

Classification of Oronasal Fistulae in cleft palate

Oronasal fistulae can be classified into different types from Type I, a bifid uvula, to type VII, labial alveolar fistula[1]. Focusing on Type V (a fistula at the junction of the primary and secondary palates), Type VI (a lingual alveolar fistula) and Type VII (labial alveolar fistula), these oronasal fistulae can be further classified into small (<2 mm), medium (2–5 mm) and large (5 mm), as well as symptomatic or nonsymptomatic fistulae. A treatment algorithm presented by Denadai and Lun-Jou[1] for oronasal fistulae notes that if patients have a symptomatic fistula with no velopharyngeal insufficiency then the fistula can be repaired at any time. If the fistula is small, with mild scarring, it can be repaired with a local flap. For small to medium sized fistula with severe scarring, one option is to redo the palatoplasty. It is really only for large fistulae with severe scarring that a tongue flap may be used. It is also important in such cases to assess the velopharyngeal function in the patient at the same time[1]. Additionally, Denadai et al noted in their description of a therapeutic protocol for persistent symptomatic anterior oronasal fistulae, that in small or medium (≤5 mm) fistulae local flaps with interpositional grafting may be the flap of choice whereas for large (>5 mm) type V to VII fistulae a two-stage tongue flap could be considered[2].

Dr Lu explains that for small and medium fistulae, a turned-over marginal gingiva or mucoperiosteal flap and sometimes an interpositional graft can be used on the nasal side. On the oral side, mucoperiosteal or gingivomucoperiosteal flaps and buccal mucosa flaps can be applied for anterior hard palatal fistulae and alveolar fistulae. For the large fistulae, she notes that a turned-over marginal mucoperiosteal or gingivomucoperiosteal flap plus vomer flaps can be used for the nasal side, whereas on the oral side, anteriorly based, midline-positioned tongue flaps can be applied. These are then divided two weeks later. Referring to a case discussed by Denadai et al. she pointed out that surgeons should be aware that sometimes defects initially look small and may only be categorized as a type II defect, but once maxillary expansion and orthognathic surgery have happened, the oronasal fistula is actually much larger and reflects a type V to VII defect[1]. When such cases occur, successful outcomes can be achieved with a tongue flap reconstruction.

Alveolar oronasal fistula after orthognathic surgery

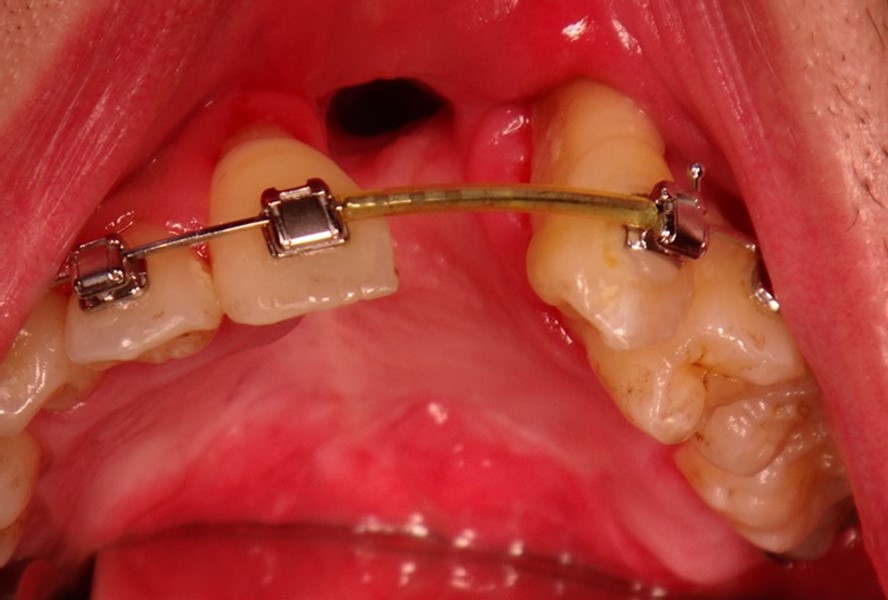

Putting this theory into practice, Dr Lu went on to present a difficult case of alveolar oronasal fistula after orthognathic surgery. “The patient was a young boy with unilateral complete cleft lip, class III malocclusion, open bite, and occlusal cant. In this case, the patient had previously had bone grafting, but a collapse of the lesser segment had occurred. Being symptom free, it was difficult to know whether there was a fistula present or not. The plan of action was to try and solve the problems at the same time as the orthognathic surgery. Here, we performed a Le Fort I two-piece osteotomy or the maxilla at the left alveolar cleft site and separated it into a right and left segment. We shifted the lesser segment outwards to align the teeth. However, during surgery, I could feel that it was difficult to move the lesser segment forward due to a lot of scarring of the soft tissues”. Two months later, Dr Lu saw that the patient had developed necrosis of the soft tissue and bone necrosis around the central incisors.

CT scan confirmed the diagnosis showing that the patient had a large oronasal fistula. “The question was, what do we do next? In such cases there are a few options. We could wait for a smaller oronasal fistula, perform a local flap with interpositional graft, do a two-stage tongue flap, redo the osteotomy to close the gap or even perform interdental distraction osteogenesis” commented Dr Lu. She agrees that most people choose to do a two-stage tongue flap, but in her case, she waited until she felt confident enough to close the fistula. In this case, it was a good idea because at 1-year the tissue had started to stabilize, and half a year later the fistula was smaller.

However, because the alveolar bone around the tooth was not healthy, Dr Lu had to avoid cutting the mucosa around the tooth. The technique of choice in the end was a limited local flap with two layered closure, using a tongue flap to close the nasal flap.

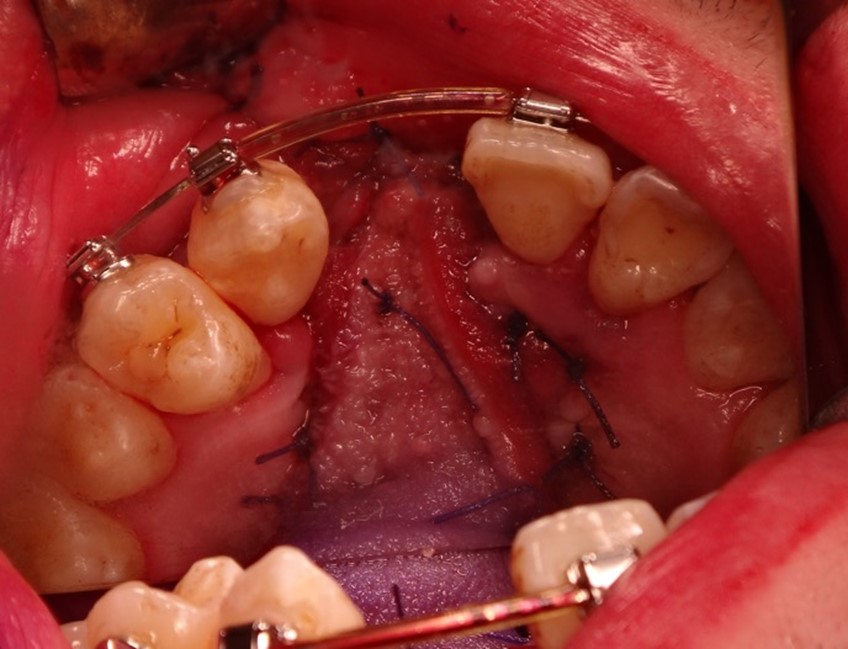

A complex anterior palatal fistula in a young child

Such fistulae in the young child are complex cases to manage, and it can be difficult to know what the right strategy is. This was exemplified by the case of a five-year-old born with a bilateral cleft lip and palette additionally presented by Dr Juna Gurung during the AO CMF Global Study Club. After early lip and palette repair, the patient presented at the age of 5 years with an anterior palatal fistula. In such cases there are multiple options available for repair including closing during alveolar bone grafting, performing a single layer turnover flap, a double layer closure, using an obturator, or performing maxillary expansion followed by alveolar bone grafting, but it is important to understand the limitations of the clinical setup. Most would agree that in this case the ideal scenario would be maxillary expansion followed by alveolar bone grafting, however in places where, for example, regular follow up is not possible, this just might not be an option. Dr Lu presented an alternative solution which could be to first remove any teeth affected by caries and then to try and use a double layered tongue flap to close the fistula. This leaves open the option of performing a bone graft at a later stage, particularly when the situation stabilizes. In the case discussed in the Study Club, the treatment of choice was to use a turnover flap for the nasal layer and a Burian flap from the labial mucosa, a successful treatment in this patient. Other options were proposed depending on the patient’s concerns at the time: if speech problems are present then the oronasal fistula could be closed first, otherwise expansion followed by bone graft and then closure of the fistula would be an option.

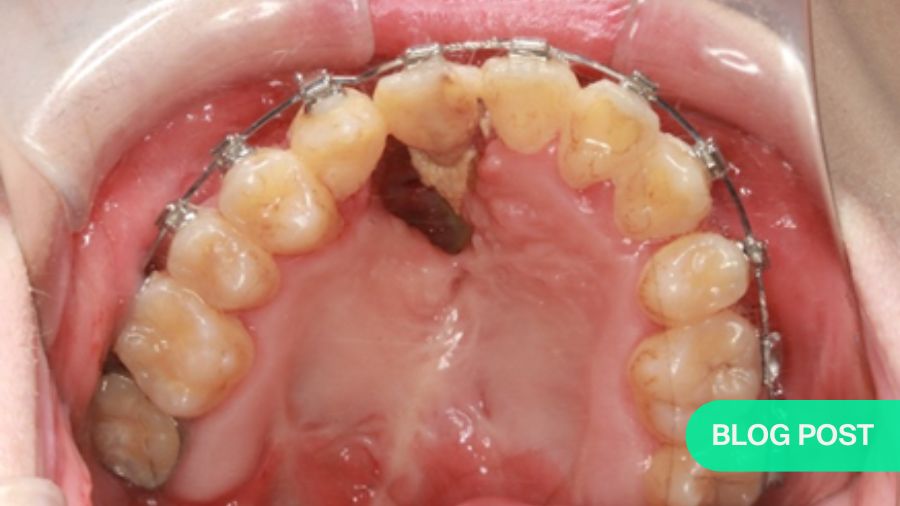

In terms of the principles of management of the management of the oronasal fistula, Dr Lu normally performs initial soft tissue coverage followed by bone reconstruction. After the soft tissue coverage, if the gap is of an acceptable size, then alveolar bone grafting can be done, whereas if the gap is big, then the two options available are interdental osteogenesis distraction and bone grafting[3] (which can be a convenient choice if the materials for osteogenesis distraction are available), or segmental osteotomy and bone grafting[4].

Management of large oronasal defects post-palatoplasty

In cases of young patients presenting with large oronasal defects after palatoplasty with both soft-tissue and bone dehiscence, management can be complex. Treatment options include redo palatoplasty, a bilateral buccinator myomucosal flap for lateral defect coverage, to redo the soft palate and cover the hard palate defect with a free flap, or to redo the soft palate and use a palatal obturator to cover hard palate defect. In such a case, Dr Lu prefers to perform a bilateral buccinator myomucosal flap for lateral defect coverage, as a redo palatoplasty may be difficult if there is a lot of scarring and this could be difficult to manage. Free flaps are difficult in young children, and although redoing the soft palate and using a palatal obturator is possible, compliance with the obturator may be difficult in young children. When using a bilateral buccinator myomucosal flap, Dr Lu noted that in her experience there may be some initial necrosis in the anterior part and maybe some dehiscence in the most distal part, but eventually there was healing. For such large defects of 3 to 4 cm, tongue flaps are not recommended because the flap would not be large enough to cover the defect in young children. Other options may also include using a temporalis flap, or if the greater palatine artery is intact, then to create an island flap based on the greater palatine artery and cover the defect anteriorly, and to additionally use a buccinator flap.

Learning curves in oronasal fistulae

Difficult cases are great learning opportunities; in reflection, Dr Lu said that looking back at her case, it may have been better to do a maxilla expansion before orthognathic surgery. Referring to a study by Watts et al[5] it is recommended to minimize the need for segmental surgery, and if maxillary width requires expansion, this should be done before a Le Fort orthognathic surgery if it removes the need for segmentation of the maxilla.

For Dr Lu the AO CMF Study Club is a great opportunity to exchange opinions on difficult cases, learning from other surgeons, and getting new ideas. As Dr Pradhan—the moderator of the discussion—said, “we learn from our mistakes, better to say, surgeons learn from their complications”.

About the author:

Dr Ting-Chen Lu is Assistant Professor at Assistant Professor at the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. Notably, she serves as the Director of the Operation Room at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan. She underwent her training in plastic and reconstructive surgery at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Linkou, Taiwan. She initially specialized in craniofacial trauma and in 2013 focused on cleft lip and palate surgery. She pursued a pediatric craniofacial fellowship at Sickkids Hospital in Toronto, Canada from 2016 to 2017. She has performed over 500 primary cleft surgery experiences, conducted more than 100 cleft orthognathic surgeries, and has performed numerous secondary cleft surgeries. She also has experience in craniosynostosis surgery.

References and further reading:

- Current Concept in Cleft Surgery. 1 ed. Denadai R, Lo LJ, editors: Springer Singapore; 2022.

- .Denadai R, Seo HJ, Lo LJ Persistent symptomatic anterior oronasal fistulae in patients with Veau type III and IV clefts: A therapeutic protocol and outcomes. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(1):126-133.

- Liou EJ, Chen PK, Huang CS, Chen YR. Interdental distraction osteogenesis and rapid orthodontic tooth movement: a novel approach to approximate a wide alveolar cleft or bony defect. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(4):1262-1272.

- Inoue A, Tsuji M, Baba Y, Moriyama K. Non-prosthetic treatment using segmental osteotomy and bone grafting in a patient with cleft lip and palate. Plastic and Aesthetic Research. 2022;9:51.

- Watts GD, Antonarakis GS, Forrest CR, Tompson BD, Phillips JH. Single Versus Segmental Maxillary Osteotomies and Long-Term Stability in Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Related Malocclusion. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2014;72(12):2514-2521.