Artificial intelligence in scientific writing: practical support and ethical boundaries in medical and veterinary research

BY DR ANDERSON FERNANDO DE SOUZA AND DR ALFREDO GUIROY

Scientific writing is often described as a craft that demands precision, objectivity, and clarity. Yet for many clinicians and researchers, especially in surgery, orthopedics, and experimental medicine, writing is one of the most time-consuming steps of the research cycle. The increasing availability of artificial intelligence (AI) tools is reshaping this landscape. When used responsibly, AI can enhance scientific productivity, support non-native English speakers, and help researchers better connect clinical practice with data-driven investigation.

However, these gains come with limitations and ethical responsibilities. This article explores how AI can support scientific writing in medical and veterinary fields, while highlighting the boundaries of responsible use.

-

Read the quick summary:

- The authors explain how AI can support scientific writing in orthopaedic, surgical, and veterinary research while defining ethical and professional limits.

- AI improves drafting speed, clarity, and structure but requires human verification, transparency, and strict adherence to research ethics.

- Orthopedic surgeons can use AI to draft, refine, and organize manuscripts while retaining full responsibility for data accuracy and interpretation.

- Ongoing discussion focuses on journal policies, disclosure standards, and how to balance AI efficiency with scientific voice and integrity.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

A Clinical Seminar—AI Tools and New Technologies: Challenges and Opportunities for Research at the annual AO Latin America Regional Courses on August 19, 2026, in Santiago, Chile, chaired by the authors will explore the integration of AI and emerging technologies in research and provide surgeons with a comprehensive overview of how AI can transform research methodologies, improve the quality of evidence, and foster innovation across the global AO network.

Why AI matters for clinician-scientists

In both human and veterinary medicine, clinicians face mounting pressure to publish, teach, and contribute to translational research. But time is finite. Literature has expanded exponentially in musculoskeletal science, biomaterials, biomechanics, and fracture care. Reviewing, organizing, and synthesizing such material can easily overwhelm even experienced authors. AI technologies address part of this challenge by offering:

- Faster drafting of scientific text

- Improved clarity and language quality

- More systematic approaches to literature exploration

- Support for structuring complex research questions

- Tools that help bridge clinical experience with evidence-based writing

Notably, AI does not replace scientific expertise. Instead, it amplifies when handled with care.

Practical applications for clinical and experimental researchers

1. Accelerating the early stages of manuscript writing

The blank page is often the biggest obstacle. Large language models (LLMs) can help clinicians start writing more efficiently by generating:

- Outlines for manuscripts

- Alternative titles and subtitles

- Logical flow suggestions

- Abstracts based on structured inputs

- Lists of potential keywords

- Narrative explanations of complex concepts

For example, a researcher studying fracture healing process can request an outline that integrates immunology, biomechanics, mechanobiology, and clinical outcomes. This saves hours of initial drafting and helps structure ideas before writing the final version. However, the researcher remains responsible for validating all content.

AI-generated text should be considered a drafting assistant, not a source of unquestioned facts.

2. Improving readability and English language quality

For many clinicians, English is not their first language. AI can support in:

- Grammar and style revisions

- Rephrasing sentences for clarity

- Adapting tone to meet journal expectations

- Transforming technical explanations into reader-friendly text

It is a fact that well-written manuscripts have higher acceptance rates. Tools that improve clarity without altering scientific meaning can help level the playing field for global researchers. Still, authors should avoid “AI over-polishing,” which may obscure their authentic scientific voice or raise concerns about transparency.

Most journals now request acknowledgment when AI-assisted tools are used.

3. Supporting literature exploration, but not replacing systematic reviews

AI can help summarize and compare groups of articles, generate thematic maps, or explain conflicting findings. This is particularly useful for:

- Orthopedic biomaterials research

- Imaging and diagnostic studies

- Translational surgical investigations

- Experimental animal models

However, LLMs must not replace structured systematic-review methods. They can miss studies, introduce bias, or confuse study designs. AI can support the early exploratory phase, but all systematic searches must rely on validated protocols (PRISMA, database-specific strategies, etc.).

4. Assisting in data interpretation (with caution)

Some AI tools can help:

- Identify statistical tests appropriate for data types

- Explain results in natural language

- Detect inconsistencies in tables and figures

- Rewrite results sections for clarity

For example, in a retrospective study analyzing infection rates after internal fixation, AI can help articulate the meaning of logistic regression outputs or organize survival curves in a coherent narrative. Yet AI cannot replace statisticians. It may misinterpret results, propose inappropriate analyses, or produce overly confident statements. All interpretations must be reviewed by trained researchers.

5. Applications for orthopedic and surgical research

Orthopedics and trauma care offer unique opportunities for AI-assisted scientific writing because the field generates large amounts of measurable, structured data. For instance, when preparing a manuscript on cortical thickening and remodeling after fracture repair, AI can help structure the introduction (context/background, problematization, justification, objectives and hypothesis), suggest ways to present tables and timelines, improve clarity in describing radiological findings, supporting the discussion by connecting outcomes to existing literature.

But again, clinical judgement drives accuracy. AI helps communicate findings, not create them.

Ethical boundaries, risks, and responsibilities

1. Accuracy and “AI Hallucinations”

AI may produce statements that sound authoritative but are incorrect or unsupported. In scientific writing, this is a serious risk. Strategies to avoid this include:

- Verifying all references manually

- Using AI only to rephrase, not to generate factual claims

- Consulting original sources before including citations

- Checking whether described mechanisms or results actually exist

2. Transparency and declaration of use

Most journals now require authors to declare the use of AI tools in writing, explicitly state what tasks AI performed, and confirm that all scientific responsibility remains with the authors. This protects integrity and ensures clarity for reviewers.

3. Protecting confidential and clinical data

A fundamental responsibility when using AI tools in scientific writing is to ensure that confidential or sensitive information is never compromised. Clinicians and researchers must avoid entering any form of identifiable patient data, unpublished proprietary material, trade-sensitive information, or experimental findings that have not yet been publicly disclosed. These types of content may pose legal, ethical, and intellectual property risks if processed through external AI platforms.

The only exception is when an institution provides approved, secure, and compliant systems specifically designed to handle sensitive or confidential datasets. In all other cases, users should restrict AI interactions to non-identifiable, fully anonymized, or already public information.

4. Preserving scientific voice

Excessive dependence on AI can unintentionally dilute the unique scientific voice of an author. When overused, these tools may reduce originality, homogenize writing styles, and suppress the subtle clinical insights that arise from firsthand experience.

Scientific communication often depends on elements that AI cannot reproduce, such as nuanced interpretation, professional judgment, and the distinctive perspectives gained through years of clinical and research practice. Editors and reviewers consistently value these human dimensions, which enrich manuscripts with clarity, context, and authenticity.

5. Authorship and ownership

The use of AI tools in scientific writing does not alter the fundamental criteria for authorship. AI cannot be listed as an author, as it cannot take responsibility for study design, data integrity, or the interpretation of findings. It functions solely as a tool, no different in principle from a grammar checker or reference manager. Proper authorship requires substantial intellectual contribution, accountability for the accuracy and integrity of the work, and approval of the final manuscript. These responsibilities remain exclusively human.

Conclusion

AI is already transforming into how medical and veterinary researchers write, communicate, and share scientific knowledge. In orthopedic and surgical research, where clinical insights meet data-rich environments, AI tools can significantly reduce barriers to writing and enhance clarity, especially for researchers who juggle clinical responsibilities with academic demands.

However, the value of AI depends entirely on how it is used. Responsible use requires transparency, verification, and a firm understanding that AI supports, but never replaces the human expertise, clinical judgement, and scientific integrity. The future of scientific communication will likely be hybrid: human-driven, AI-enhanced, and centered on rigorous, ethical research practices. With thoughtful adoption, AI can help clinicians tell their stories, share their findings, and contribute even more effectively to the global scientific community.

Declaration of AI Use

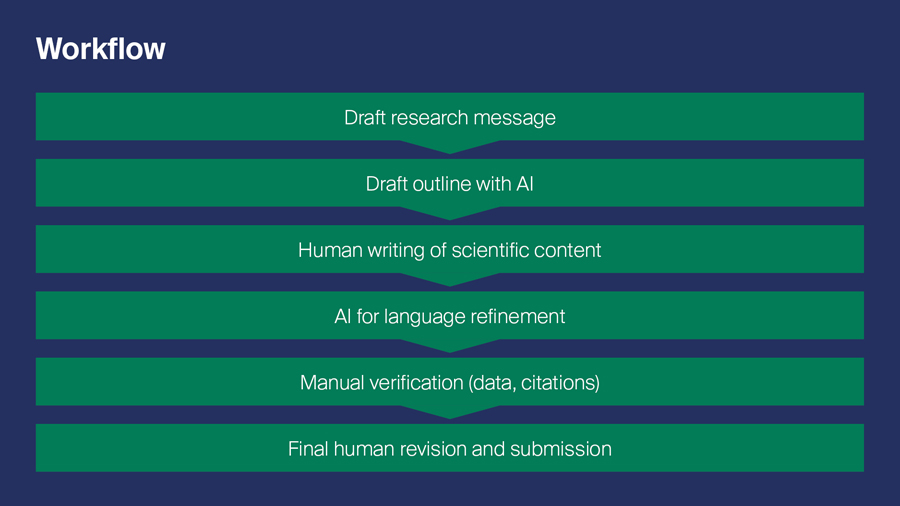

This article was developed with assistance from the AI-based tool ChatGPT, which supported text drafting, language refinement, and generation of illustrative figures. All scientific concepts, interpretations, and final content decisions were reviewed, validated, and approved by the authors.

About the authors:

References and further reading:

- Celik, S. U. (2025). Integrating artificial intelligence into scientific writing: a narrative review for clinical and surgical researchers. The American Journal of Surgery, 250, 116657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2025.116657

- Hryciw, B. N., Seely, A. J., & Kyeremanteng, K. (2023). Guiding principles and proposed classification system for the responsible adoption of artificial intelligence in scientific writing in medicine. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 6, 1283353. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2023.1283353

- Giglio, A. D., & Costa, M. U. P. D. (2023). The use of artificial intelligence to improve the scientific writing of non-native English speakers. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira, 69(9), e20230560. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20230560

You might also be interested in...

AO Course Finder

The AO provides accredited and high quality educational activities to thousands of surgeons and health care professionals each year.

AO PEER

The knowledge platform especially designed for health care professionals who want to learn and improve their clinical research skills.

AO video hub

A vast collection of educational videos, recorded lectures, seminars, and webinars at the fingertips of our members.

AO NextGen

The global young surgeons’ initiative by AO, where you’ll meet peers who share your ambitions and challenges.