Orthognathic Surgery: from wired jaws to 3D planning

BY DRS NICOLAS HOMSI, TRAVIS TOLLEFSON, AND PATRICIA STOOR

Over the past few decades, orthognathic surgery has undergone a remarkable transformation. What once began with limited tools, long recovery times, and primarily functional aims has evolved into a specialty that combines precision, aesthetics, and improved quality of life for patients worldwide. As surgeons, educators, and lifelong learners, we have had the privilege of witnessing, and contributing to, these advancements across different stages: the past, the present, and the future.

At the AO Davos Courses, where education and innovation shape the next generation of cranio-maxillofacial (CMF) surgeons, this conversation is especially relevant. Here, we share perspectives on how orthognathic surgery has developed, where it stands today, and where it may lead us in the years ahead.

-

Read the quick summary:

- Nicolas Homsi, Travis Tollefson, and Patricia Stoor trace the evolution of orthognathic surgery from manual cephalometric tracing and wired fixation to rigid fixation, digital workflows, and 3D simulation.

- Rigid fixation and virtual planning have improved precision, efficiency, aesthetics, and patient satisfaction.

- From a clinical perspective this means shorter orthodontic phases, fewer revisions, more predictable results, better harmony of function and appearance.

- The future of orthognathic surgery may include AI-assisted planning, enhanced soft tissue prediction, minimally invasive techniques, and bioresorbable fixation/distraction systems.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

When cephalograms and casts defined the field

Looking back nearly a century, orthognathic surgery began with the first osteotomies, simple yet groundbreaking steps toward correcting severe malocclusions and jaw discrepancies. By the 1950s, procedures such as the Le Fort osteotomies became more standardized, giving us a framework we continue to refine today.

In those early days, planning was manual and time-consuming. Surgeons relied on cephalograms, hand-traced X-rays, and plaster dental casts. Outcomes were functional, often correcting chewing or severe deformities, but considerations for facial harmony and aesthetics were limited. One of the most significant milestones came with the shift to intraoral approaches, followed later by the introduction of internal fixation.

Before rigid fixation, patients endured weeks, sometimes months, of maxillomandibular fixation, living with their jaws wired shut. The adoption of stable internal fixation represented a paradigm shift. Patients could regain oral function faster, recover more comfortably, and benefit from greater surgical precision. For many of us, this moment stands out as a turning point, moving orthognathic surgery from experimental to accessible, with a deeper impact on patients’ lives.

The modern era introduced digital tools and precision care

Fast forward to where we are today, and orthognathic surgery has entered the digital era. At its core, what has changed is not only how we plan surgeries, but also how efficiently and predictably we can achieve outcomes.

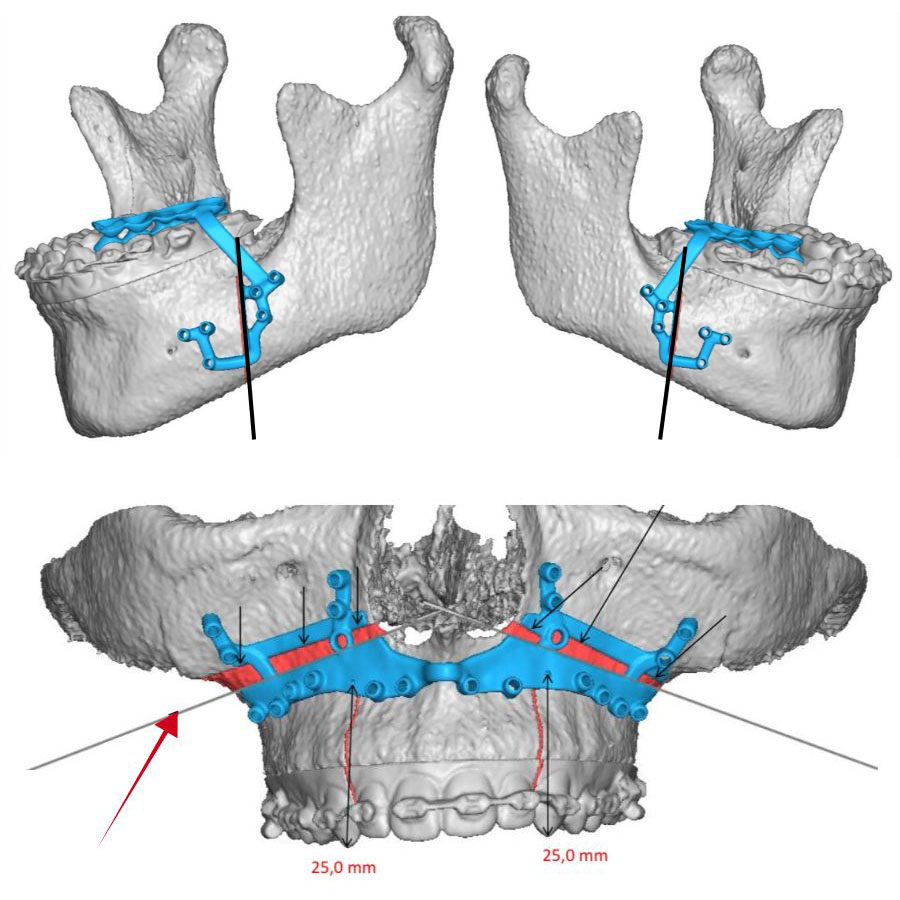

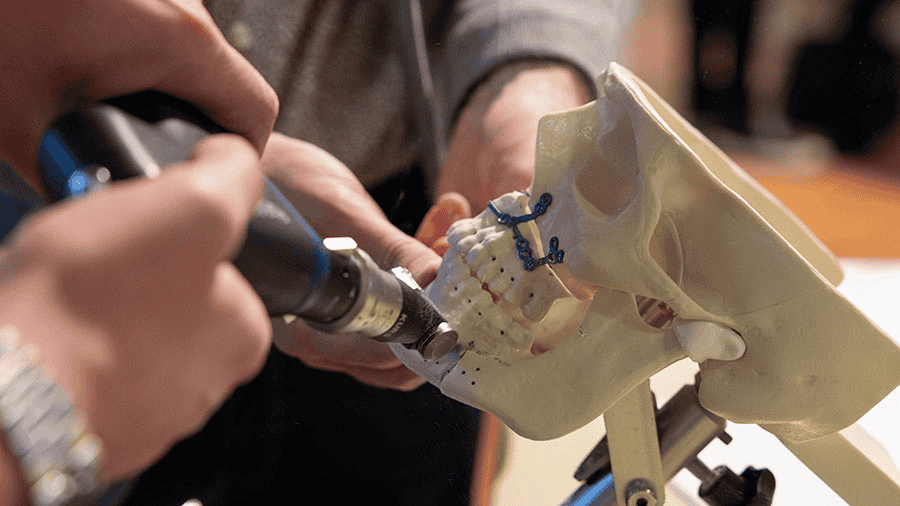

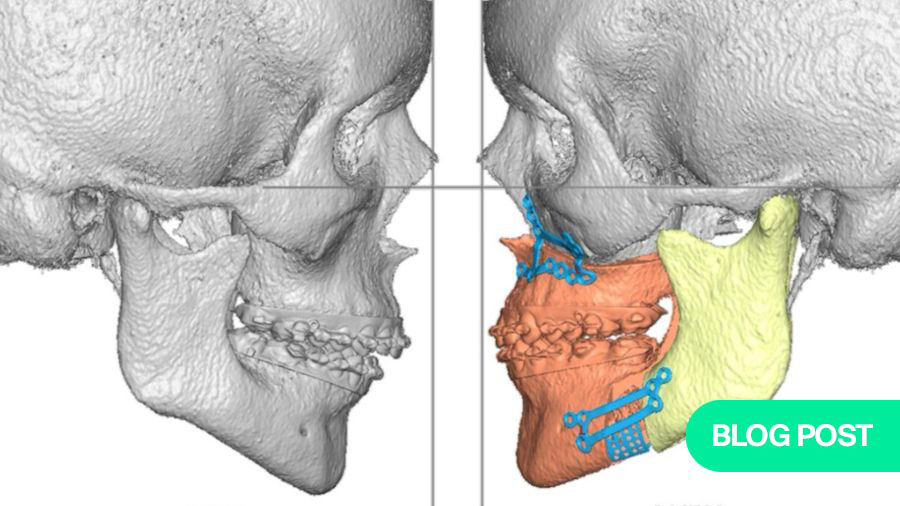

Through computer-assisted planning, surgeons and orthodontists collaborate using virtual models that allow us to plan skeletal movements down to the millimeter. Cutting guides and patient-specific implants translate these plans into the operating room, ensuring accuracy and reducing intraoperative decision-making stress. The time previously spent on manual model surgery, cutting, repositioning, and gluing casts, has been replaced with 20 minutes of digital adjustments. That efficiency not only saves time but also helps standardize the quality of planning across different centers.

For patients, the benefits are equally profound. Orthognathic surgery can now address both functional and aesthetic outcomes with greater reliability. For example, patients with cleft lip and palate often experience dramatic improvements in airway, occlusion, and facial proportions through digitally planned procedures. Moreover, the precision of bone repositioning has improved the predictability of soft tissue changes, contributing to more balanced and natural facial profiles.

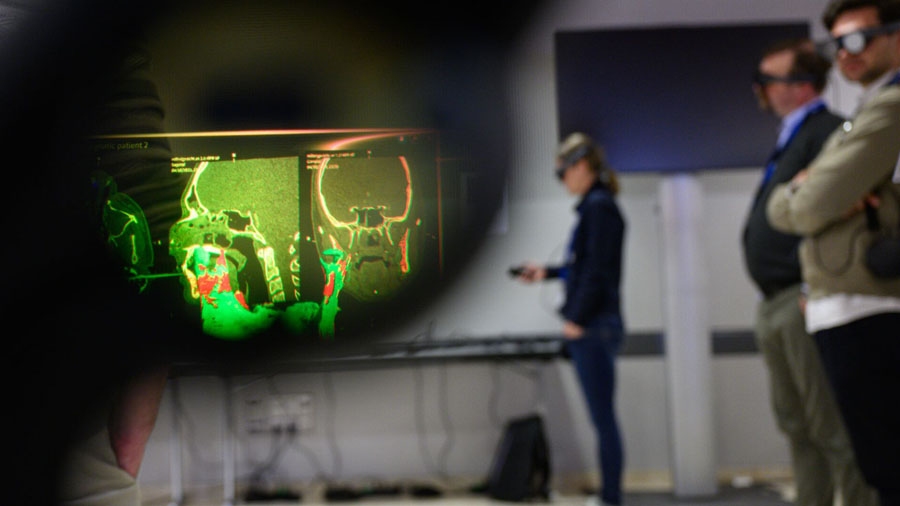

Beyond cleft patients, the shift toward 3D simulation has widened our understanding of facial harmony. We can now visualize, anticipate, and discuss appearances with patients, bridging the once-considerable gap between surgeon planning and patient expectations. These are conversations rooted not only in occlusion but also in self-image, identity, and psychological well-being.

Proportions and 3D planning take center stage

Another fundamental change has been the increasing emphasis on facial proportions rather than occlusal correction alone. Twenty years ago, many cases could be resolved with single-jaw surgery. However, today we recognize that considering facial harmony often requires two-jaw approaches with careful assessment of soft tissue support.

The role of 3D planning is invaluable here. Unlike traditional cast-based approaches, which placed reliance on intraoperative judgment, digital tools offer preoperative visualization of multiple scenarios. Surgeons now enter the operating room with clarity regarding vertical, sagittal, and transverse positioning—the elements that determine long-term stability and aesthetic balance.

We also see an advantage in managing patients with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) issues or condylar pathology. Digital planning allows surgeons to better preserve and control condylar positioning, minimizing risks of relapse or dysfunction. The precision gained here has also resulted in shorter postoperative orthodontic phases and reduced rates of revision surgeries.

Looking ahead to the future of orthognathic surgery

Standing where we are today, it is tempting to imagine where orthognathic surgery may take us in the next two decades. While we cannot predict it with certainty, several technological and conceptual directions are already visible.

1. Artificial intelligence and patient libraries

Artificial intelligence (AI) holds great promise for expanding treatment libraries and supporting less experienced surgeons. Imagine case repositories that allow users to compare real-world outcomes across different ethnic backgrounds and skeletal patterns to determine ideal surgical goals. AI-driven predictions may also refine preoperative orthodontics, a critical area where root resorption and treatment complications remain a challenge.

2. Improved soft tissue simulation

One gap we still face lies in accurately predicting soft tissue outcomes. While current systems provide good approximations, there remains variation between simulated projections and actual results. Advances in soft tissue modeling could create a tool that improves planning for both function and esthetics, leading to more precise patient counseling and surgical execution.

3. Minimally invasive orthognathic surgery

Current use of patient-specific guides and implants often requires larger exposures. Future solutions may integrate navigation and augmented reality to limit dissection while maintaining precision. The possibility of true minimally invasive orthognathic procedures could reduce recovery times and postoperative morbidity while preserving accuracy.

4. Next generation osteosynthesis and distraction

A particularly exciting frontier is the development of resorbable distraction devices integrated directly into fixation systems. These could one day be activated digitally, making bone movement adjustable in real time with external guidance. Imagine devices that not only achieve distraction but also serve as consolidation plates, eventually resorbing without the burden of hardware removal surgery.

From wires to virtual reality: a specialty transformed

What began with wired jaws has now moved into an era of digital precision, interdisciplinary collaboration, and patient-centered outcomes. Orthognathic surgery has evolved into a specialty that drastically improves function and aesthetics, while also addressing psychological and social aspects of patient care.

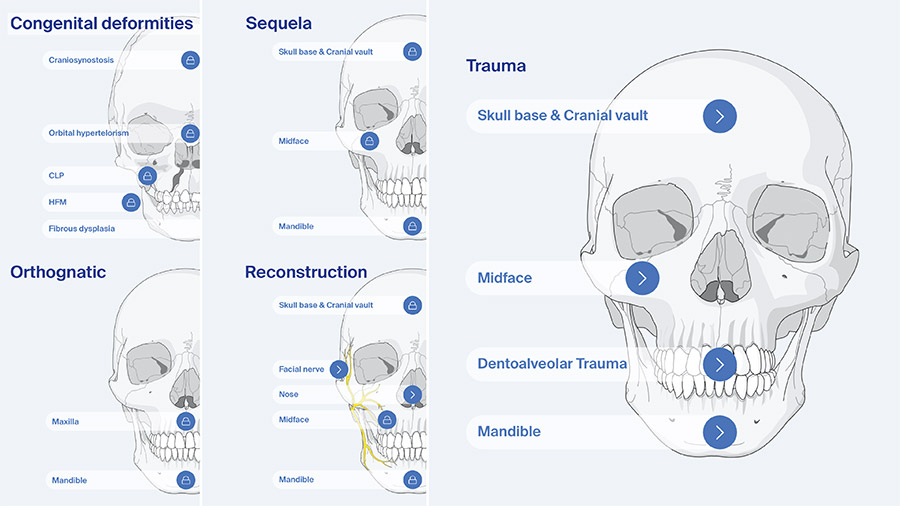

Education remains central to this progress. As part of the AO Davos Courses, we are proud to offer programs that introduce foundational skills as well as advanced applications of new technologies. Our collective goal is to prepare the next generation of CMF surgeons to not only master today’s techniques but also to embrace and refine the innovations of tomorrow.

Looking ahead, the future of orthognathic surgery appears bright. Advances in virtual planning, biomaterials, augmented reality, and AI are no longer distant ideas but active areas of exploration. These tools hold the potential to enhance patient outcomes, streamline workflows, and expand access to life-changing surgeries.

For us as surgeons, the true reward remains in seeing the profound impact these procedures have—whether correcting sleep apnea, harmonizing facial appearance, or restoring function in complex cleft cases. Orthognathic surgery will continue to transform lives. And as educators, innovators, and clinicians, we look forward to contributing to this ongoing journey.

About the authors:

Dr Nicolas Homsi, DDS, OMFS, is an oral and maxillofacial surgeon specializing in craniomaxillofacial trauma, reconstruction, and orthognathic surgery. He trained in dentistry in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and got his Masters and PhD in São Paulo, Brazil.

Currently based in the US at Marquette University, Dr Homsi manages complex facial trauma and deformities while also performing facial esthetic procedures. He is an active AO CMF faculty member, contributing to international education and research, and is committed to advancing surgical practice and mentorship.

Dr Travis Tollefson, MD, MPH, FACS, is a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon with expertise in cleft and craniofacial surgery. He trained at University of Kansas and then at the University of California Davis, and is currently Professor and Director of Facial Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Surgery at UC Davis. He also serves as Co-director of the UC Davis Cleft and Craniofacial Program.

His clinical and research work focuses on cleft lip and palate, craniofacial anomalies, and facial paralysis, with a strong emphasis on global outreach and education. As an active AO CMF member, Dr Tollefson contributes to international training initiatives and has been recognized as a leader in advancing collaborative, patient-centered reconstructive care worldwide.

Dr Patricia Stoor, DDS, MD, PhD, is an oral and maxillofacial surgeon specializing in craniomaxillofacial trauma, reconstructive surgery, and orthognathic procedures. She serves as Head of Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Diseases at HUS, Helsinki University Hospital and is Associate Professor at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Additionally, she is also Councilor of Finland in the International Association.

Her clinical and academic focus spans virtual surgical planning, 3D printing, and patient-specific implants in facial reconstruction. She is a previous member in the PSSTF and member of AO CMF R&D Commission, the AO CMF ESA Board, and the AO CMF Orthognathic Task Force. Dr Stoor is dedicated to advancing digital innovations in surgery and training the next generation of surgeons through international education and mentorship.

You might also be interested in...

Orthognathic surgery resources

Explore a curated library of clinical tools, cases, and techniques in orthognathic surgery.

Cranio-maxillofacial education

Discover upcoming courses, events, and learning opportunities designed for CMF surgeons worldwide.

CMF Trauma Surgery Reference

Access AO’s step-by-step, evidence-based reference for managing fractures and injuries of the cranio-maxillofacial skeleton.