A life sciences ecosystem: how 3D printing and virtual planning is transforming surgical outcomes for CMF patients

BY DR FLORIAN THIERINGER

As Chairman of Oral and Craniomaxillofacial Surgery at University Hospital, Basel, Professor Florian Thieringer has integrated technology seamlessly into clinical practice. So much so, that he says his residents use digital tools as naturally as they do pen and paper. For oral and CMF surgeons, these are not just the latest gadgets but essential tools in delivering precision, saving time intraoperatively, and delivering minimally invasive approaches. For patients undergoing reconstructive surgery following trauma or cancer, the results are literally life changing.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

Here, Professor Thieringer discusses a young patient whose double vision was cured with the help of 3D modeling and a patient-specific implant. This case is part of a clinical portfolio that demonstrates not only the diversity of the OCMF specialty but also the opportunity to work at the cutting edge of scientific innovation.

Smart implants deliver precision and reduce intra-operative time

University Hospital Basel is the largest healthcare provider in Northwestern Switzerland. Together with our children’s hospital, we cover all the specialties in oral and CMF surgery—from cleft lip palate reconstruction to craniofacial operations, tumor surgery, obstructive sleep apnea, and orthognathic surgery. We are really proud to be able to provide that comprehensive level of training for all of our residents.

I live in a city house in central Basel, just a five-minute bike ride from the hospital, which is important to me because I can get up around 6 am and have some time with my daughters, Lilly and Pauline, before arriving at work at 7:30. A typical day starts with a meeting of the whole surgical team, followed by rounds and office work on days I am not operating. There is a lot of management and meetings involved with running a department, which is essential, but like most surgeons, I love being in the OR.

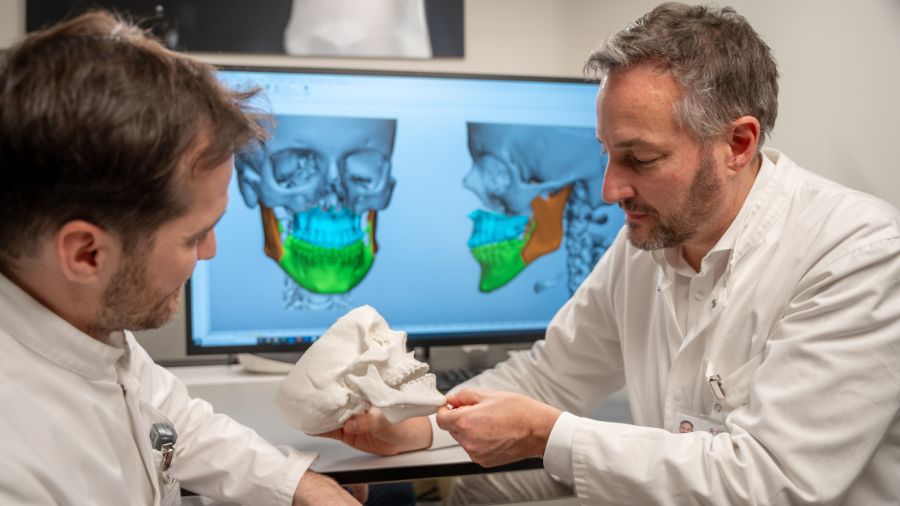

One particular interest of mine is smart implants, which include 3D-printed patient-specific implants, bioprinting technology, sensor technology, or implants fabricated with a particularly interesting material. We had a particularly interesting case that demonstrated the benefits of a completely integrated digital workflow. The patient came to us with a protrusion of the left eye, an exophthalmos, and the beginnings of double vision. When we did the CT scan, we quickly realized the patient had a benign tumor growing in the orbit, pushing the globe forward.

I founded a 3D printing lab at Basel nine years ago, so we have a fully digital clinic in craniomaxillofacial surgery. When the CT scan revealed the tumor, we were therefore able to send a request to the 3D printer directly from the patient file, and the printer took care of the diagnostics and planning. Because it’s a full-color anatomy printer, it can create visuals of the patient in different colors and segment the tumor and the mesh used to treat the initial fracture of the orbital floor and wall. The tumor had grown through this implant, so both needed to be removed. The print lab segmented the eye muscle, nerve, globe, implant, and tumor. They then worked with a spin-off team of our Department of Biomedical Engineering to produce a patient-specific titanium implant.

This entire workflow was completed digitally before we performed the surgery. We were able to remove the tumor and mesh, reconstruct the medial orbital wall, place the titanium implant to cover the defect, reconstruct the orbital wall and floor and rehabilitate the patient, all in one operation. We also used intraoperative imaging and navigation to guide the implant to the correct position. Like a car with satellite navigation, it takes you where you want to be and shows you where you are in relation to the patient’s anatomy. Then, when you snap back the eyelid at the end of the procedure, you see nothing.

Seamless digital workflow enables MI approaches to reconstructive surgery

These technologies require the team to invest time pre-operatively to save time intra-operatively. I recently treated a female patient who had temporal hollowing following an operation when she was young. As well as viewing her scans on the computer, we could 3D print a soft tissue mask of the patient, which allowed us to check whether the 3D-printed patient-specific implant would fill up the defect area in her skull perfectly. This is particularly valuable to help patients to visualize their end results, and they are super interested in the process.

Our workstream is seamless because we have Medical Device Regulations (MDR) Approved Workflow, which allows us to plan and produce patient-specific cranial implants made from polyetheretherketone (PEEK). I used this in a recent surgery for a patient with a tumor of the frontal bone that had to be removed. We designed an individual cutting guide to remove the tumor and a patient-specific implant made of PEEK, which was printed right next to the OR in advance of the operation and then fitted precisely.

Without these tools, this would have been a long and complex reconstruction, potentially with less accuracy. With super high-res imaging technology, we know where we need to place the implant and can, therefore, take smaller approaches, resulting in less scarring and shorter operation and anesthesia times. It enables a minimally invasive approach to surgery and results in reduced complications and a shorter length of stay. It’s a unique workflow that allows us to rehabilitate the patient perfectly.

Walking in the footsteps of giants

One of the most rewarding aspects of my job is that our residents are not only trained in CMF but also learn to use digital tools as if they are paper and pen. It’s so natural to their daily work that they take it for granted. They simply live and love it, and that’s something I really appreciate.

For young surgeons coming into the specialty now, they are not just undertaking research that will come to fruition in 10 years or more, or never. They are actually getting to integrate it into their clinical practice and see how it benefits their own patients right now. Basel has hosted some of the giants of CMF and our shared history is very important to us. I remember experiencing that at the very beginning, as a young resident myself, getting in contact with fellows all over the world to learn from one another. It is what has motivated me to remain very active in the AO for nearly 10 years. I’m particularly interested in community development and looking at how we can bring the younger generation forward and support surgeons internationally to build professional networks. I recently returned from the Davos conference having experienced four fantastic days with highly motivated participants from all over the world. We should always focus on excellence in our discipline, but also look ‘over our plate’ at other divisions such as spine, orthopedics and vet, to see what’s going on there and what we could implement in our own work. AO is really unique – I’ve never experienced a community like it.

Video:

An artificial skull cap was implanted for the first time in a patient at the University Hospital Basel (USB) in August 2023. After years of research and development, the USB is the first hospital in Europe to successfully produce implants using 3D printing that meet the requirements of international medical device standards.

About the author:

Professor Florian Thieringer is Chair and Full Professor of Oral and Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery at the University Hospital Basel and the Head of the Medical Additive Manufacturing Research Group (Swiss MAM) at the University of Basel's Department of Biomedical Engineering.

He is an internationally recognized expert for computer assisted surgery and medical additive manufacturing, extensively exploring and promoting the integration of virtual surgical planning, 3D printing and other innovative technologies at the point-of-care. Prof Thieringer is editor-in-chief of the journal ‘Craniomaxillofacial Trauma and Reconstruction’ and a member of several international expert panels and committees. Since 2016 Prof Thieringer is Co-Director of the multidisciplinary 3D Print Lab at the University Hospital of Basel. Since 2020 he is Co-Principal Investigator of the innovative MIRACLE 2 project (Minimally Invasive Robot-Assisted Computer-guided LaserosteotomE), which aims to develop a robotic endoscope to perform contact-free bone surgery with laser light. He is co-applicant and since 2021 on the steering committee of the University Hospital Basel flagship project ‘Innovation Focus Regenerative Surgery’. Florian Thieringer is Community Development Commission member and representative in the AO CMF board for Europe and Southern Africa and Editor in Chief of the Journal of Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction (CMTR).

You might also be interested in:

AO CMF Global Study Club

A dynamic platform for AO CMF members to discuss cases, share experiences, and network effectively.

Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction

AO CMF's official scientific journal CMTR is devoted to the study and treatment of craniomaxillofacial conditions. Access the latest research evidence and submit your research.

AO CMF Guest Blog

Diverse views and perspectives from the craniomaxillofacial community around the world. Submit your proposal and support our mission to share knowledge and improve patient care.