Restoring facial balance using a creative, cost-effective approach—how a customized unilateral wing osteotomy corrected mandibular asymmetry

BY DR GUILHERME LOUZADA

A patient who was about to get married wanted to correct a long-standing facial asymmetry before her wedding day, but a sudden change in circumstances meant that traditional orthognathic surgery was no longer an option. In this case study, Dr Guiherme Louzada takes us through how he and his team used virtual planning and 3-D printed surgical guides to carry out a customized unilateral wing osteotomy and achieve a successful aesthetic result under restricted conditions.

Dr Guiherme Louzada's case presented in this Guest Blog was the winner of the myAO Case Competition 2025.

-

Read the quick summary:

After a sudden change in circumstances, traditional orthognathic surgery was not an option for a patient who wanted to correct a long-standing facial asymmetry.

-

Use of a PMMA prosthesis or mandibular base osteoplasty were considered, but the optimal approach was a customized unilateral wing osteotomy.

-

Dr Guiherme Louzada takes us through how he and his team used virtual planning and 3-D printed surgical guides to achieve a successful aesthetic result under restricted conditions.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

As a maxillofacial surgeon, I’ve learned that the most powerful outcomes often emerge not just from clinical expertise, but from empathy, creative problem-solving, and collaboration. This was particularly true in the case of a young woman preparing for her wedding—an occasion meant to be filled with joy, but which was overshadowed by insecurity. Her concern was facial asymmetry, more specifically an uneven mandibular contour that had always made her feel self-conscious.

Though she had been in preparation for orthognathic surgery for a year (including orthodontic treatment), when her circumstances changed dramatically. Her husband lost his job, she lost her insurance, and suddenly full orthognathic surgery became financially unfeasible. But she remained hopeful and motivated, and my goal was to help her achieve her dream safely, affordably, and effectively.

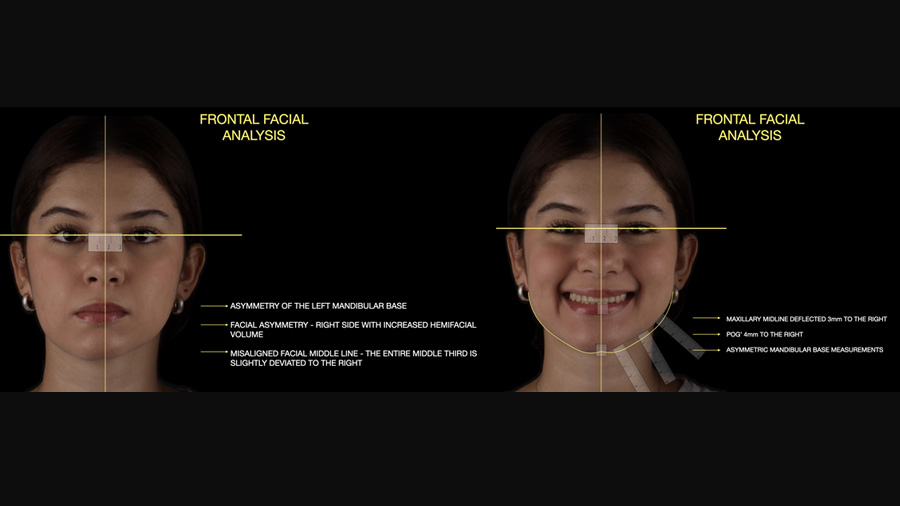

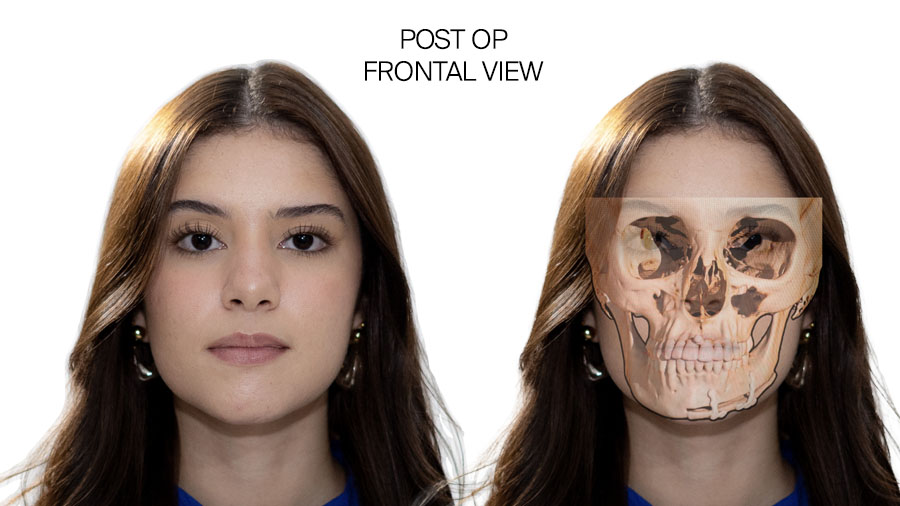

From a clinical standpoint, this case presented with classic characteristics of facial asymmetry involving the mandibular base. During facial analysis, we observed the entire maxillomandibular complex deviated to the right, with vertical imbalance, hemifacial hypertrophy, and yaw-axis deviation. There was also a 1–1.5 mm cant with the lower left side depressed, and clear deviation of both the maxilla and the mandible toward the right. However, the sagittal profile was well-balanced, with good positioning of the upper lip, lower lip, and pogonion (chin prominence).

Functionally, the patient had no occlusal instability or masticatory dysfunction. The asymmetry, though noticeable to the trained eye, was subtle to the untrained one. Yet for the patient, the difference was glaring—her right jawline was fuller, more contoured, while the left side appeared underdeveloped. She was deeply unhappy with her self-image.

Given the financial and time constraints, full bimaxillary orthognathic surgery was no longer an option. What we needed was a less invasive, lower-cost alternative that could be performed within a relatively short timeline and still produce meaningful aesthetic improvement.

Initially, we considered three main options:

1. Use of a PMMA prosthesis (polymethyl methacrylate):

While this approach could augment the deficient left mandibular side, it would introduce potential risks including contamination, displacement, and issues with prosthetic adaptation. Moreover, the cost could be prohibitive.

2. Mandibular base osteoplasty (bone shaving) on the right side:

While this would certainly reduce the asymmetry, it would also shorten the face—a counterproductive outcome given that the patient preferred the fullness of her right side. Reducing the side she liked wasn't in line with her aesthetic goals.

3. Unilateral wing osteotomy to reposition and advance the left mandibular base:

This offered a minimally invasive way to effectively address the asymmetry by enhancing the left side rather than compromising the right. It also aligned with the patient’s aesthetic preference and was surgically feasible in a public hospital setting.

Though much less common, this third option was ultimately the most appropriate choice.

Virtual planning and 3D customization

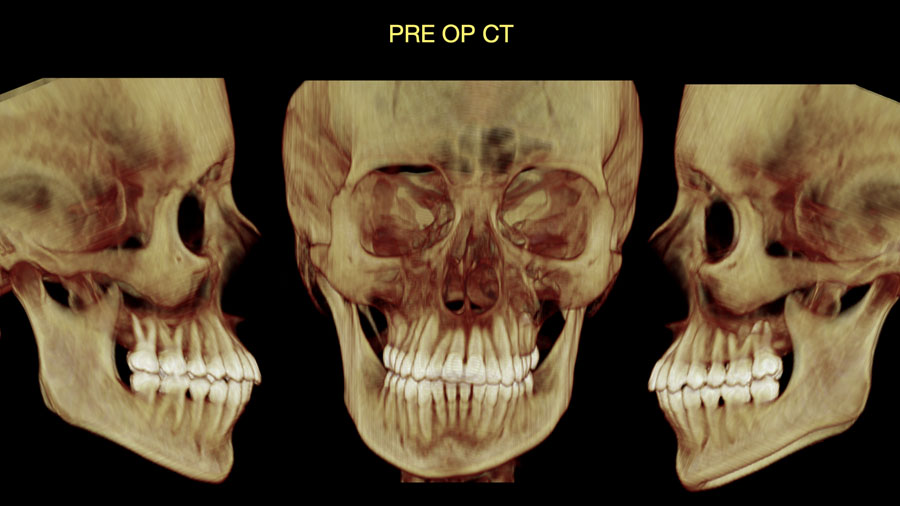

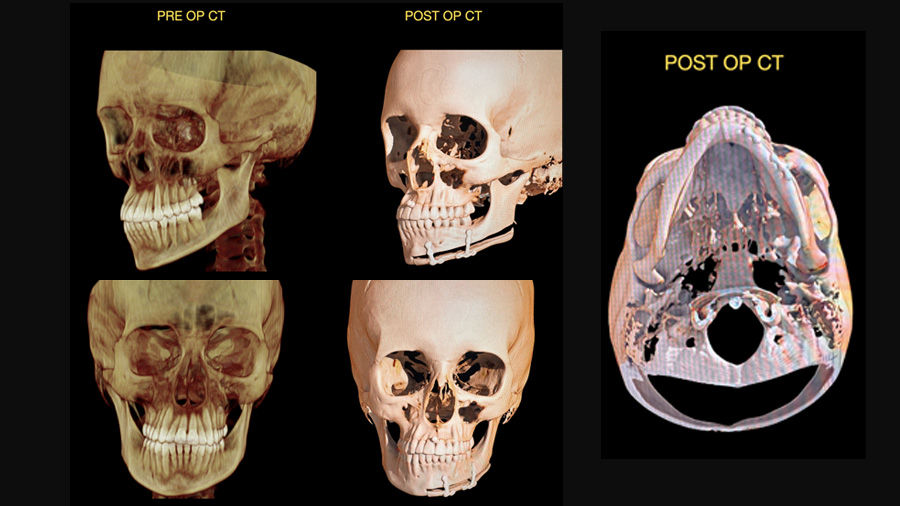

Precision was critical. To ensure success, we employed digital planning tools extensively. We began by converting the patient’s CT data from DICOM to STL format, allowing us to manipulate the 3D structure of the mandible digitally.

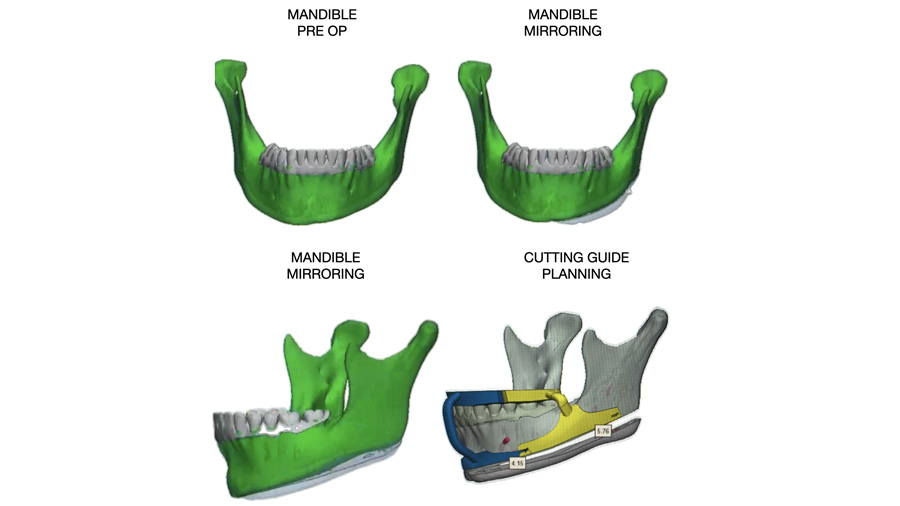

Using a mirroring technique, we replicated the patient’s right mandible onto the left side to assess the volume and shape discrepancy. The mirrored image revealed an exact strip of missing bone volume on the left that accounted for the asymmetry—effectively quantifying the issue we needed to correct.

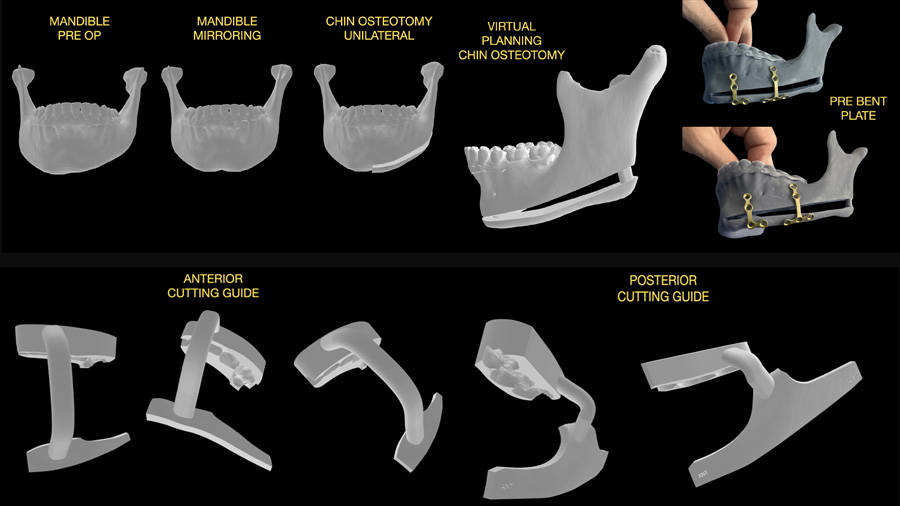

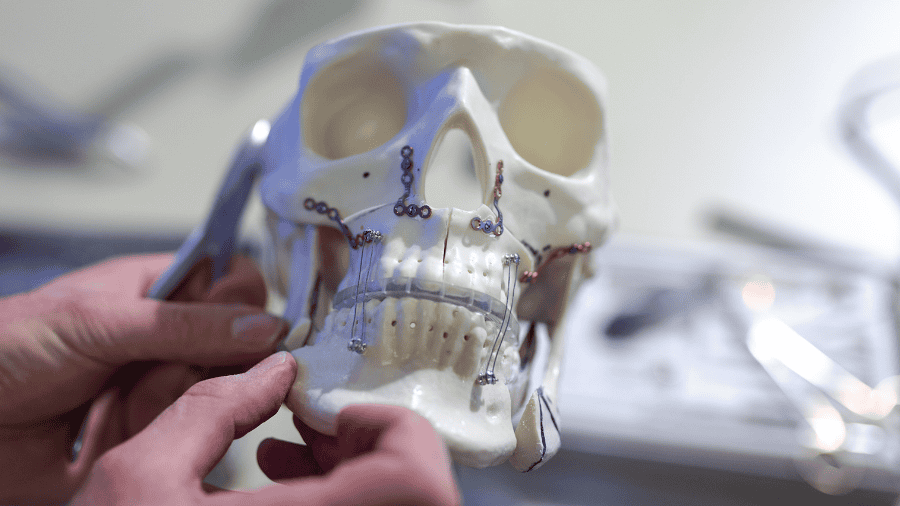

This digital model allowed us to design a customized cutting guide that would direct the osteotomy with high precision from the symphysis to the gonial angle. To further aid surgical execution, we printed two biomodels: one representing the mandible in its original form, and one in the post-operative planned configuration.

Using these models, we pre-bent the fixation plates that would be used in surgery, aligning them exactly to the desired final shape and gap. This step was crucial in reducing intraoperative guesswork and ensuring accurate placement.

By the time we entered the operating room, we had in our hands a patient-specific cutting guide, pre-contoured hardware, and a clearly visualized plan for a precise and reproducible osteotomy.

Surgical technique and challenges

The surgery was performed in a public hospital setting in Brazil, which posed some logistical constraints. Notably, we lacked a piezoelectric surgical unit—an ideal tool for precision bone cutting. This absence meant we had to use traditional instruments without compromising the precision of our plan.

To ensure the stability of the cutting guide during surgery, we designed it in two separate pieces—an anterior and a posterior segment—each adapted to the occlusal surface. This approach helped lock the jaws into position, reducing reliance on an assistant to hold the guide in place. With the guide secured, we began by marking the osteotomy path with a 702 drill. Once the pathway was defined, we completed the bone cut using a reciprocating saw, taking care to stay within the limits defined by our 3D planning.

Because we were not using piezoelectric tools, it was necessary to dissect more tissue to access the surgical site. This was a trade-off we accepted in exchange for maintaining the integrity of the osteotomy trajectory. Once the segment was mobilized, we placed the pre-bent plates, carefully aligning them with the biomodel reference. Their precise shape and fit allowed us to stabilize the advanced mandibular segment exactly as planned.

There were no complications during the procedure, and all hardware fit seamlessly. In retrospect, the use of piezoelectric equipment would have simplified the osteotomy process and reduced tissue trauma, but even in its absence, we achieved our goals without compromise.

Postoperative results

Two weeks after the procedure, the patient returned with excellent healing and visible improvement in facial symmetry. The left side of the mandible now matched the right side in contour, creating a balanced and aesthetically pleasing lower face. Importantly, her occlusion remained unchanged, and there were no functional impairments. The satisfaction on her face—and her excitement about her upcoming wedding—made it clear that we had addressed not just a physical imbalance, but a long-standing emotional concern.

While her case would have traditionally called for a more invasive and comprehensive orthognathic approach, this focused and personalized solution achieved almost the same results for a fraction of the cost.

For surgeons considering a similar approach, here are my practical recommendations:

- Start with accurate virtual planning. Use mirroring to simulate correction and measure the exact degree of required movement.

- Design dual-part osteotomy guides (anterior and posterior) to improve stability and reduce intraoperative variables.

- Adapt your guides to the patient’s occlusion, ensuring that the jaws are locked in place during surgery to prevent misalignment.

- Use piezoelectric equipment if available to make precise cuts with minimal trauma.

- Pre-bend fixation plates using biomodels to save surgical time and improve accuracy.

- Have a grafting strategy ready for cases with larger bone gaps—either synthetic blocks or particulate grafts combined with biological enhancers like L-PRF.

Virtual planning proved indispensable in this case. The ability to simulate outcomes, mirror anatomy, and produce cutting guides allowed for a level of precision that would have been impossible with a more freehand approach. This digital groundwork, combined with the use of 3D-printed models for pre-bending fixation plates, streamlined the surgery and considerably reduced operative time.

Resource limitations, while challenging, can also encourage innovation. The absence of advanced tools forced us to rely on meticulous preparation and adaptable techniques. Dividing the cutting guide, ensuring stable occlusal adaptation, and rehearsing the hardware placement all contributed to overcoming these limitations successfully.

This case also reinforced the notion that facial aesthetics matter deeply to patients. What may appear to be a minor asymmetry to a clinician can feel monumental to the individual, and it’s important to treat those concerns seriously. Furthermore, another valuable insight I gained was the value of customizing treatment not only to anatomy but to the patient’s personal and socioeconomic context. By focusing on the feature that truly bothered her—the asymmetry of the mandibular base—we were able to design a surgical approach that was ultimately less invasive, more affordable, and had a high impact.

Ultimately, however, for me this was not just a surgical success but a human one. We did not just correct bone, but we restored confidence, fulfilled personal dreams, and navigated challenges with innovation and empathy. It was a good reminder of why we do what we do.

About the author:

You might also be interested in...

myAO

The fast-growing, trusted digital network of trauma and orthopedic surgeons worldwide, to connect and securely exchange knowledge.

AO Surgery Reference

Your go-to resource for the management of fractures, based on current clinical principles, practices, and available evidence.

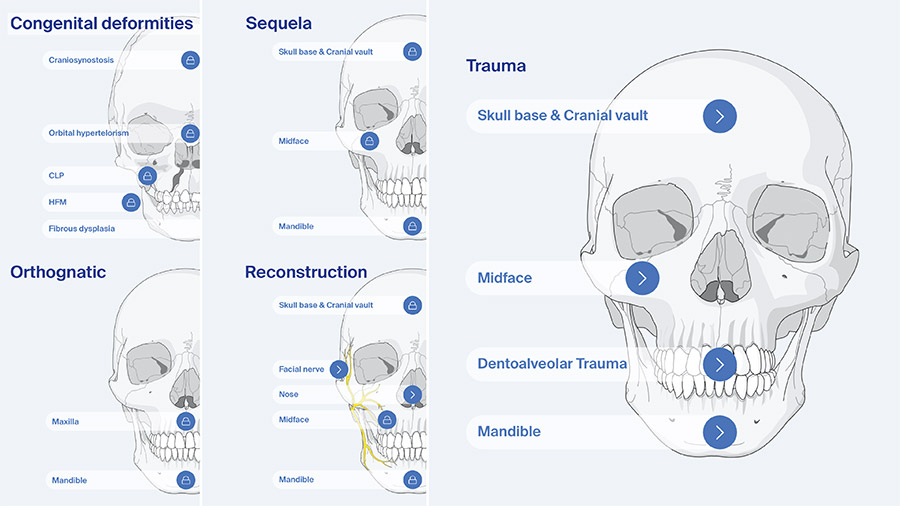

Further resources on orthognathic surgery

Explore AO CMF’s resources on craniomaxillofacial orthognathic surgery.

Global Study Club

A dynamic platform for AO CMF members to discuss cases, share experiences, and network effectively.