When there’s no textbook: performing a rare pectus excavatum surgery in a cat

BY HÜSEYIN KORAY AKDENIZ

This case report outlines a rare surgical intervention for severe pectus excavatum in an adult cat, where standard supportive care was no longer effective. Practicing in Kuwait with limited access to advanced resources, Hüseyin Koray Akdeniz adapted principles from human thoracic surgery to design a patient-specific approach using titanium reconstruction plating. Here, he offers practical insights into case selection, surgical planning, and post-operative management in a setting without established protocols.

Hüseyin Koray Akdeniz's case presented in this Guest Blog was the winner of the myAO Case Competition 2025.

-

Read the quick summary:

- A young cat exhibited worsening symptoms owing to pectus excavatum, a congenital chest wall deformity

- After research and consultation with a human thoracic surgeon, a surgery plan was developed

- Surgery involved removing the influence of work on specific bones and musculature, rhinoplasty, and the addition of a titanium plate

- Post-operatively, the cat has shown significant improvements, both physically and in terms of quality of life

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

When this case first came through our doors, I had no idea it would turn out to be one of the most complex and rewarding surgical experiences of my career. As a veterinarian practicing in Kuwait, I had seen my fair share of pectus excavatum cases—a congenital chest wall deformity where the sternum and costal cartilages cave inward, compressing the lungs and heart. But rarely do these cases demand surgical intervention. Most animals, despite the deformity, lead fairly normal lives with supportive care, such as bronchodilators, oxygen therapy during respiratory distress, and occasional treatment for secondary issues such as pneumonia.

This case, however, was different from the start. The patient, a one-and-a-half-year-old Scottish Fold cat, had been living with severe symptoms that were steadily worsening. The owners had been seeking help for months. They’d been advised by several veterinarians, even at larger and better-equipped hospitals, that surgery was too risky and should only be attempted at a specialized referral center abroad.

Unfortunately, travel wasn’t an option for the family, leaving them with weekly – sometimes biweekly – emergency visits to stabilize the cat with oxygen and medications. The cat was barely able to eat without gasping for air, couldn’t walk more than a few steps, and certainly couldn’t play or interact like a normal pet. Its quality of life was alarmingly poor.

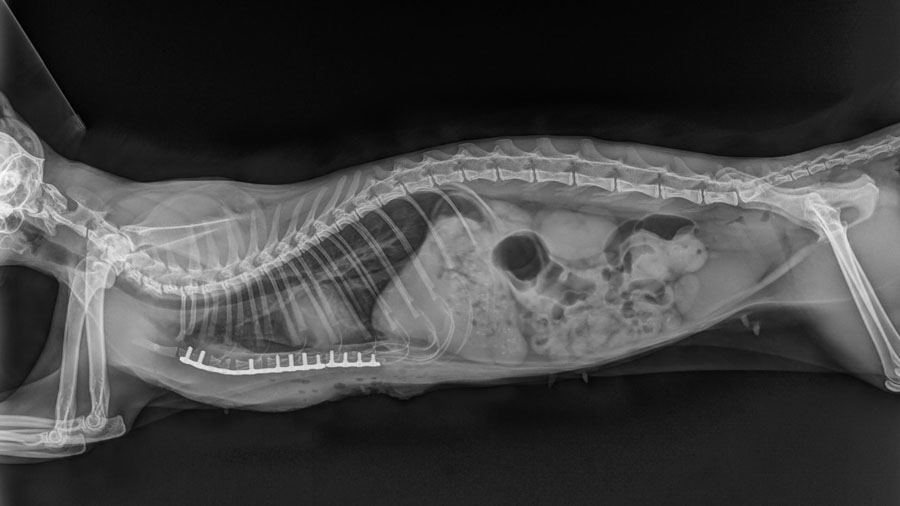

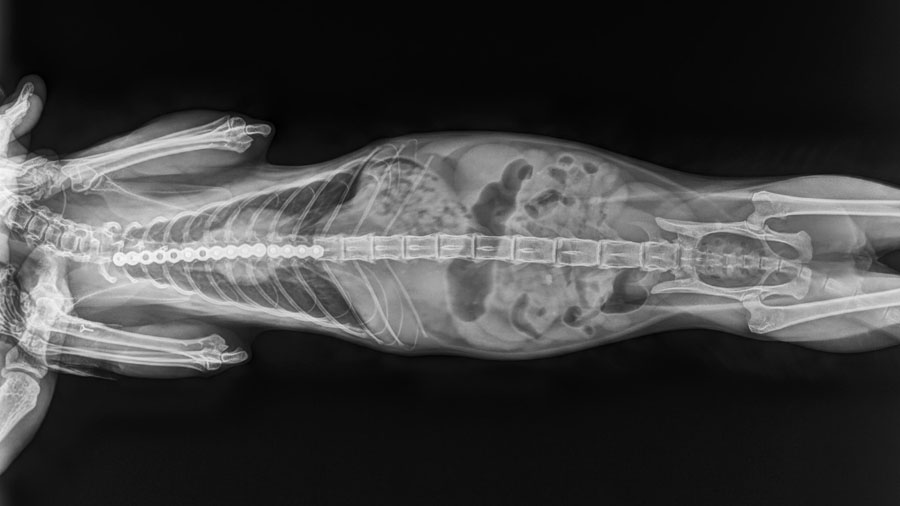

When I met the owners, they had simply come in seeking another temporary relief. But after examining the cat and reviewing the imaging— X-rays during inspiration and expiration showed just how dramatically the chest wall collapsed with every breath—I knew this wasn’t just a case for palliative care. It was a candidate, albeit a risky one, for surgical intervention.

To be honest, I had never performed a pectus excavatum surgery with this type of dynamic change before this case. In fact, even in academic and clinical settings, it’s a surgery most vets will only encounter once or twice in their careers. During my veterinary education, I had never seen one firsthand. Literature on the procedure is sparse, especially for cases performed beyond the optimal window of two to three months of age. That’s the age when the chest is still pliable, and external splints can be used to guide the sternum outward as the kitten grows. This cat, however, was well beyond that stage.

In the Middle East, and especially in Kuwait, early detection of congenital deformities like this is still inconsistent. Veterinary practices here are very competent in symptomatic care, but less experienced with early intervention for anatomical abnormalities. This cat had slipped through the cracks.

What made me consider surgery was partly the desperation of the family—but also the realization that there were no remaining options. I explained to the owners that this would be a high-risk, high-reward procedure, but that it could dramatically improve their cat’s life. They were surprised. Every other vet had told them the opposite. After doing their own research and reflecting on the progressive deterioration they were witnessing, they gave me their trust and agreed. With that, I began preparing.

The first step was research—lots of it. I combed through the limited literature available, but the more I read, the more I realized how little consistency there was. It soon became clear that there was no standardized protocol, no long-term data, and highly variable outcomes. Most similar cases operated on past the early developmental window usually ended in failure. There were more resources on treating brain tumors in animals than there were on chest abnormalities.

Adapting human thoracic surgery for pectus excavatum in adult cats

That uncertainty was daunting. But then, serendipity played a part. Around the same time, I began treating a dog injured in a car accident. Its owner turned out to be the dean of the medical university in Kuwait—a human thoracic surgeon. Over several discussions, we compared our approaches. He explained the logic behind various methods used in human medicine: metal bars to support the sternum, anatomical reinforcement, and the importance of identifying the key points where the chest collapses. That conversation became a turning point in how I approached this case.

Instead of trying to follow an existing formula, we built our plan around the cat’s unique anatomy. Using X-rays and video studies, I identified the "breakdown points" in the chest wall—the areas of maximum inward deviation and instability. I noted which costal cartilages were contributing to the deformity and which vertebral sternal segments were overly flexible or weak.

Our surgical plan was to remove the influence of the problematic ribs by severing their connection to the sternum. We would then reinforce the weakened sternal segments with a bent titanium reconstruction plate, designed to mimic the natural contour of a healthy sternum. It wasn’t a fancy, custom 3D-printed solution—we don’t have that capability here—but it would be strong enough and adaptable enough to offer real structural support.

We also decided to perform a rhinoplasty during the same operation. The cat suffered from stenotic nares—a condition where the nostrils are too narrow, restricting airflow. That added another layer of respiratory difficulty, so enlarging the nasal openings would ease breathing post-surgery and reduce strain on the newly supported chest.

The surgery itself was intense but went largely to plan. Anesthesia was one of the most nerve-wracking elements, as cats with compromised chests are high-risk under sedation. We used inhalation anesthesia with a closed system and carefully monitored the cat throughout. The surgical challenge lay in the size and fragility of the bones—we were working with sternal vertebrae as thin as 0.6mm. One segment cracked during drilling and had to be bypassed. But the rest of the implant held well, and the rhinoplasty was straightforward.

Post-operatively, we weren’t sure what to expect. The literature had conditioned me to prepare for setbacks. Instead, we were shocked by the immediate improvement.

The cat woke up breathing calmly and quietly for the first time. Within 24 hours, it was eating again—finishing an entire packet of food in minutes, whereas previously it had needed 10-15 minutes and to rest between every few bites. Within a day, it was up and walking. After a few more, it was playing. The transformation was so dramatic that even the owners were speechless. They’d prepared themselves to say goodbye just a few months earlier.

Post-operative recovery and long-term outcomes in rare feline thoracic cases

Over the next 10 days, we kept the cat hospitalized, providing antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications, and close observation. There were no signs of infection, no implant rejection, no respiratory distress. Follow-up X-rays over the next few months confirmed that the plate remained intact, and the chest structure was stable. Even better, the cat gained 50% of its body weight in three months, a sign not just of recovery but of thriving.

Of course, this doesn’t mean the story is over. We don’t yet know how the chest will adapt long-term, especially as there’s so little data on cases operated at this age. The implant may fail in future years. But for now, the outcome has exceeded every hope we had.

This case has left me with several key lessons that I believe are important for any veterinary surgeon considering a similar path. First and foremost, don’t be afraid to try. Traditional guidelines and protocols are valuable, but they can’t account for every case. In situations like this, where no exact precedent already exists, sometimes you need to create your own. That’s not reckless, it’s resourceful.

Second, collaboration matters. I’m a veterinarian, not a human doctor, but the insights shared by the thoracic surgeon I consulted were invaluable. Interdisciplinary learning expanded my view and gave me a foundation for designing a successful plan. There’s often more overlap between human and veterinary medicine than we acknowledge, and I’d encourage colleagues to seek out those connections when tackling rare cases.

Third, and this is perhaps more technical, if you’re planning to undertake a surgery like this, consider using CT imaging to map the skeletal structure and, if possible, work with a manufacturer to 3D print a custom-fit implant. That wasn’t possible for us in Kuwait, but it would have dramatically improved both the ease and precision of surgery.

And finally, choose your cases wisely. This kind of intervention isn’t appropriate for every animal or every family. Owner communication is critical, not just for consent, but for setting expectations and ensuring post-operative care is followed correctly. The success of this case was a team effort between us and the owners.

For now, this cat is living a full, joyful life. Whether that lasts another year or another decade, it has already outlived every prognosis it had before we tried. And for me, that’s reason enough to always keep pushing forward, even when the road ahead isn’t clearly marked.

About the author:

You might also be interested in...

AO Surgery Reference

A resource for the management of fractures, based on current clinical principles, practices, and available evidence.

myAO

Community access to relevant, trusted sources of knowledge, moderated case discussions, and expertise across AO specialties.

AO VET Fellowships

Opportunities for young surgeons to learn from leading AO experts in carefully selected and renowned centers.

AO Course Finder

Find accredited and high quality educational activities from AO across different pathologies. Explore your next learning activity.