Maxilla- or mandible-first approach: what is the rationale?

BY PROF FEDERICO HERNÁNDEZ-ALFARO AND DR ADAIA VALLS-ONTAÑÓN

Orthognathic surgery can be performed with either a maxilla-first or mandible-first approach. There are many reasons for choosing one approach over the other as it depends not only on the surgical indications and the desired outcomes, but also on the system used, such as patient-specific implants or patient-specific splints, the surgeon's experience, and personal preference.

In this article on different approaches to orthognathic surgery, Federico Hernández-Alfaro and Adaia Valls-Ontañón from Barcelona explain the rationale behind the different approaches introducing a recently published surgical technique using “puzzle” guides for a maxilla-first approach.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical specialties.

What are some reasons for choosing a mandible-first approach?

It is known that good clinical results can be achieved irrespective of the approach used. When considering the mandible-first approach there are five key reasons which justify its use when combined with patient-specific splints in orthognathic surgery. These include: 3-dimensional (3D) planning to compensate for errors in centric rotation, counterclockwise rotation, minimally invasive surgery, unilateral mandibular osteotomy, and temporomandibular joint reconstruction. Moreover, for esthetic and upper airway volume enlargement purposes, most patients require maxillomandibular counterclockwise rotation, and therefore the intermediate splint fits better with the mandible-first approach.

Why is a mandible-first approach important for incorrect centric rotation?

Over 12 years ago, we developed a new protocol allowing for in-house 3D surgical planning and computer aided design (CAD)/computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) generation of splints for use in orthognathic surgery [1]. This protocol meant that the splints could be produced in-house rather than being made by an external provider. Many reports in the literature discuss the accuracy of using 3D printed splints after 3D virtual planning; we showed the margin of error is within 0.1 mm compared with a surgeon's margin of error of 1 to 1.5 mm. When using the maxilla-first approach sometimes the expected outcomes were not achieved despite the case having been planned in 3D. This was because perfect centric rotation was not achieved when taking the information required for planning from the CT scan. Centric rotation can be easily achieved in many cases, but it can be difficult in dysfunctional cases, for example, when a patient has had previous temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pathology, or in cases of Class II malocclusion.

In cases of incorrect centric rotation, if the maxilla-first approach is applied then the maxilla first needs to be advanced, then descended and down grafted a few millimeters to allow room for an intermediate splint. The complex then needs to be placed into centric rotation to move the maxilla into the new position. In such a case, this would lead to malposition of the maxilla. In contrast, if the mandible-first approach is used instead, the anterior fragment would be moved to the appropriate position, the condyles would be repositioned and the condylar fragments would be positioned into the glenoid fossa, after which the subsequent osteotomy would absorb the error. This means that the result achieved with the mandible-first approach would be to have a large osteotomy gap rather than a malpositioned maxilla.

In what other situations would you use a mandible-first approach?

According to our protocol another reason to justify operating on the mandible first would be in cases with small asymmetry of the mandible where merely unilateral mandibular osteotomy can be performed. We do not recommend unilateral sagittal osteotomies to correct big mandibular asymmetries where bilateral osteotomy would be indicated.

The mandible-first approach in our described protocol is also used in cases of TMJ reconstruction. This can be exemplified by the case of a patient who had severe asymmetry provoked by ankylosis which was surgically treated when the patient was young. In this case the condyle disappeared, and the patient's hemiface grew in an asymmetric hypoplastic pattern. In addition to the problems observed with the asymmetry, the patient also had biretrusive contour, sleep apnea, and functional problems. During planning it was clear that the maxilla first approach could not be used if splints were required, because it was not possible to find good centric rotation of the mandible on the left side. As a result the mandible-first approach was adopted in conjunction with patient-specific splints. A right sagittal split osteotomy was performed, and the left condyle was reconstructed. The maxilla was fixed semi-rigidly on top of the rigidly fixed and repositioned mandible, and the TMJ was reconstructed through a small incision. In this case, the post operative clinical result matched the 3D planning; the asymmetry was corrected, there was a large counterclockwise rotation of the bimaxillary complex, and this led to good anterior projection of the face, chin, lips, and neck area.

What are some differences in the use of patient-specific splints and patient-specific implants?

In all our cases 3D diagnosis and planning has become standard. We have both the software and the tools to allow us to transfer the planning into the operating room, meaning that we can use patient-specific splints and patient-specific implants for facial, orthognathic, and reconstructive surgery, as well as trauma.

However, when moving to a new technique, such as moving from patient-specific CAD/CAM splints to patient-specific implants, the following factors need to be evaluated: invasiveness, accuracy, surgical time, price, and whether the process can be performed in house. When considering the first point, invasiveness, it has been shown that when using patient-specific implants and cutting guides only five to six incisions (involving cutting the mucosa and nasal muscles, as well as periosteal elevation) are required [2]. This is not necessarily minimally invasive surgery, and the overall aim should be towards a minimally invasive approach to advance surgical techniques in this field.

Patient-specific splints are the gold standard when it comes to accuracy, yet both patient-specific implants and manufactured splints have been shown to represent highly accurate methods for transferring a virtual surgical plan to the operating theatre [3], though patient-specific implants seem to be more accurate than splints. This could be because the splints are used in a maxilla-first protocol. In another study on splintless surgery it was concluded that the mean deviation of the postoperative maxillary dentition from the plan was 1.3 mm (standard deviation: 1.4 mm), which is within the same range as the study we published on 3D guided splints [4]. This shows that accuracy across the different systems is basically the same.

What are some disadvantages of patient-specific implants?

The patient-specific splints, which can be printed on an in-house basis have become cheap to produce and quick to make. At the same time there has been a shift towards minimally invasive surgical techniques which aim to reduce morbidity and surgical time to improve patient recovery and satisfaction. This again contrasts with the advancements in patient-specific implants, which, as described, offer an alternative to the patient-specific splints. The rationale behind this is avoiding condylar seating during maxilla and mandible repositioning, as well as reduced surgical time and slightly increased accuracy of bone reposition. But patient-specific implants have their drawbacks, in that they are dependent on third parties for both the design and manufacture of the cutting guides and implants (which leads to significantly increased costs), but more importantly, they require extensive approaches to allow for placement of the cutting guides and the fixation plates.

Can patient-specific implants be combined with a minimally invasive approach?

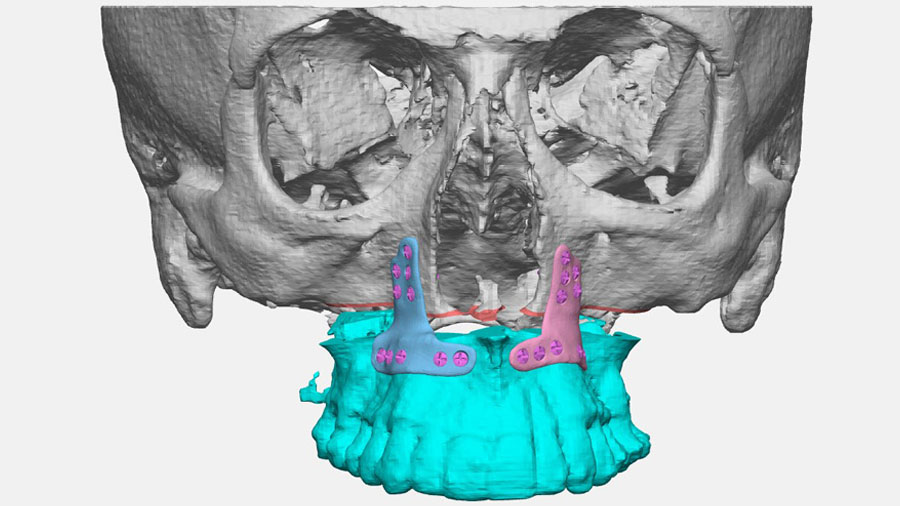

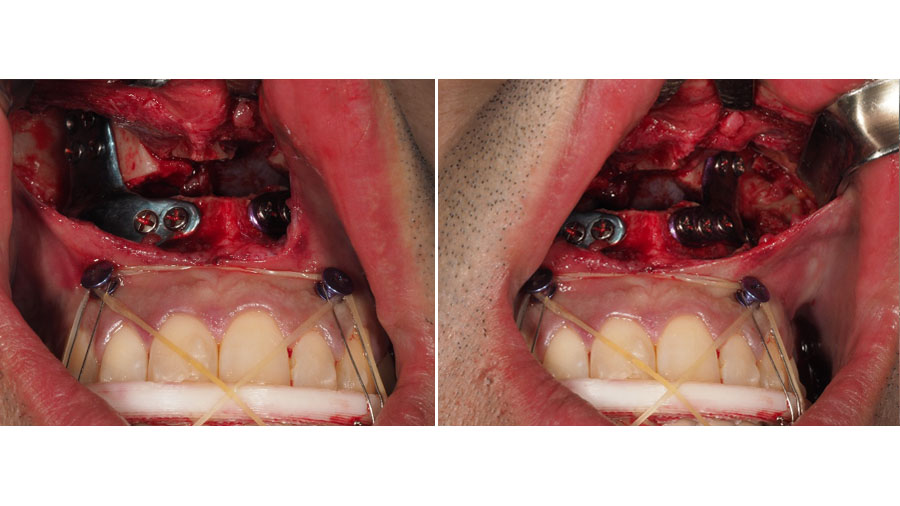

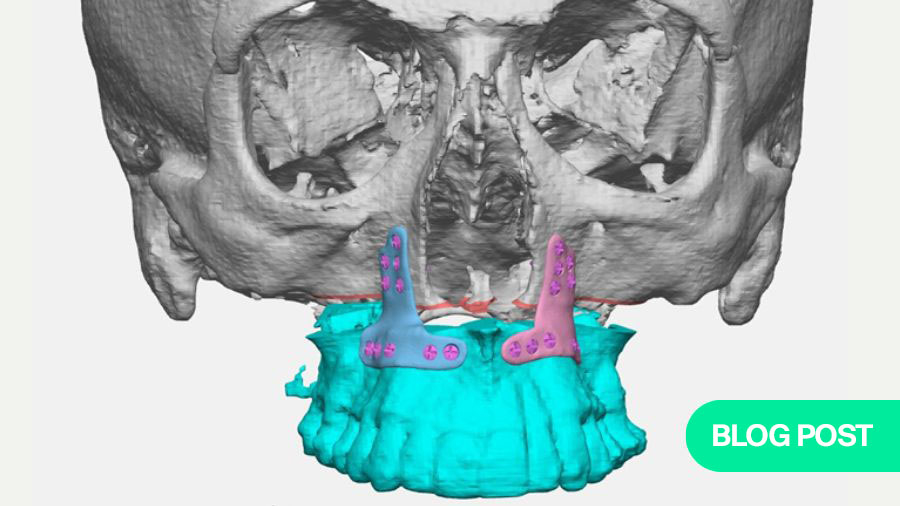

To overcome some of the disadvantages of patient-specific implants mentioned above, we recently proposed a new design and application of cutting guides and patient-specific implants developed in the context of a minimally invasive Le Fort I osteotomy [5].

We used an “inverted T” plate designed according to the planned maxillary movement and gap [5, 6]. Cutting guides were designed to allow a minimally invasive approach, in that the guides fitted the rim at the piriform aperture and extended 2 cm distal to the rim [5, 6]. The guides were assembled with a puzzle connection and secured with two screws.

Although the plates were produced externally the cutting guides were printed in-house, and at the same time an intermediate and final splint with a maxilla first protocol was printed as a backup [5, 6]. In this protocol, we performed the maxilla-first approach instead of our favored mandible-first approach [5]. After the initial surgical steps and standard Le Fort I osteotomies the preprinted custom plates were fixed with screws in the mobile maxilla, which was moved to meet the pre-drilled holes in the upper osteotomy section, thus replicating the 3D planned repositioning of the maxilla [5].

In contrast to published protocols using patient-specific implants for Le Fort I osteotomy, describing large incisions and degloving to allow positioning of cutting guides and custom plates, our protocol —using compact customized cutting guides with a ‘puzzle’ connection adapted to the piriform rim and the “inverted T” custom plates—is compatible with a minimally invasive approach [5].

Furthermore, we achieved slightly increased accuracy, which we attribute to the maxilla-first approach with rigid maxillary fixation using customized plates because there is no dependence on condylar seating for maxilla and mandible repositioning [6]. This means that potential errors in condylar positioning are avoided [5].

In sum, patient-specific splints allow for less invasive surgery than with patient-specific implants, resulting in similar accuracy, though the new protocol described by us allows for a minimally invasive, maxilla-first approach. Improvements in operating time may be able to be achieved with the compact customized cutting guides and inverted T custom plates described in our new maxilla-first protocol, though comparative studies are needed to address this question. When considering techniques, both cost and ability to plan in-house are deciding factors. Patient-specific implants are expensive whereas patient-specific splints produced in-house are more cost effective. In contrast, the patient-specific splint protocol is more surgically time-consuming, whereas the patient-specific implant protocol is more time consuming during virtual planning.

In conclusion, the mandible-first approach using patient-specific splints is accurate and allows for minimally invasive surgery in a relatively short time and the splints can be produced in-house and at low cost. On the contrary, our maxilla-first protocol with compact cutting guides and inverted T custom plates also allows for minimally invasive surgery combined with patient-specific implants. However, as of today the authors do not use mandible patient-specific implants, since their accuracy is not so reliable.

About the authors:

References and further reading:

- Hernández-Alfaro F, Guijarro-Martínez R. New protocol for three-dimensional surgical planning and CAD/CAM splint generation in orthognathic surgery: an in vitro and in vivo study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42(12):1547-1556.

- Gander T, Bredell M, Eliades T, Rücker M, Essig H. Splintless orthognathic surgery: a novel technique using patient-specific implants (PSI). J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43(3):319-322.

- Rückschloß T, Ristow O, Müller M, Kühle R, Zingler S, Engel M, et al. Accuracy of patient-specific implants and additive-manufactured surgical splints in orthognathic surgery - A three-dimensional retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47(6):847-853.

- Kraeima J, Jansma J, Schepers RH. Splintless surgery: does patient-specific CAD-CAM osteosynthesis improve accuracy of Le Fort I osteotomy? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54(10):1085-1089.

- Hernández-Alfaro F, Saavedra O, Duran-Vallès F, Valls-Ontañón A. On the feasibility of minimally invasive Le Fort I with patient-specific implants: Proof of concept. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024;125(3s):101844.

- Hernández-Alfaro F, Saavedra O, Duran-Vallès F, Valls-Ontañón A. 'Puzzle' cutting guides for minimally invasive Le Fort I: technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024;53(12):1053-1057.

You may also be interested in:

Orthognathic surgery course

Become an expert in orthognathic surgery, expanding your surgical skills, theoretical knowledge, and decision-making

Global Oral Cancer Diploma

A standardized evidence-based knowledge platform for treatment and management of oral cancer

Virtual surgical planning

Maximize accuracy and streamline orthognathic surgery with virtual planning and 3D printed plates