When to consider a Distal Femoral Osteotomy to correct femoral varus—and how to use clinical imaging data to help make the right decision

BY DR LUCAS BEIERER AND DR MARK GLYDE

Patella luxation is a common condition in dogs, but when should vets opt for surgical correction and, in more complex cases, when should vets perform a Distal Femoral Osteotomy (DFO) to correct the problem? A standing clinical examination is important, but X-rays +/- CT scans are also necessary to decide exactly what surgery is indicated and to plan the procedures—providing you know how to take and interpret such images correctly.

Disclaimer: The article represents the opinion of individual authors exclusively and not necessarily the opinion of AO or its clinical divisions.

The aim of this article is to review common femoral and tibial conformation angles and to give some examples of how to use clinical and imaging data to make decisions in managing patella luxations, particularly in more complex cases when the frontal plane offset is too great. The additional figures referred to in the article relate to the recording and the time stamp is mentioned in brackets: Corrective Osteotomies for Stifle Joint Problems: Tips, Tricks and Considerations in Planning and Execution (access AO members only).

To define skeletal deformities, we need to consider the bone in three planes (see Fig 1 at 4:51 on video). The first is the frontal plane perpendicular to the ground, which divides the bone into cranial and caudal parts. The sagittal plane is also perpendicular, but it divides the bone into medial and lateral parts. The third plane is the axial, or bird’s eye view, which is parallel to the ground and divides the bone into the proximal and distal parts. By looking at these three planes, we can assess, quantify, and qualify the deformities of any bone.

By using either X-ray or CT, and considering these three planes, we can characterize the deformities compared to normal values. (There are many publications on imaging. Atlas of Clinical Goniometry and Radiographic Measurement of the Canine Pelvic Limb by Massimo Petazzoni and Gayle H Jaeger is an excellent book, available to download and is a great reference point.)

The frontal plane and the anatomic Lateral Distal Femoral Angle (aLDFA)

Let’s start with the frontal plane, since most corrective osteotomies are on the femur (Fig 2, video 6:22). Essentially, to define any abnormality in the frontal plane, we draw the anatomic axis of the femur and then we draw the distal joint reference line (the line that connects the most distal part of the medial and lateral condyle). This gives us the anatomic Lateral Distal Femoral Angle (aLDFA).

There are numerous studies defining the normal angle, with 96° generally considered a normal aLDFA. If this angle is increased by more than 8–10°, this is consistent with significant femoral varus and is a case that is too complex to be reliably resolved with a standard 4 in 1 patella correction surgery and necessitates a corrective femoral osteotomy.

A standard “4 in 1” patella correction refers to the combination of a trochleoplasty, a tibial tuberosity transposition, lateral fascial imbrication and medial desmotomy. This combination is the most commonly necessary surgery to resolve grade 2 and grade 3 medial patella luxation (MPL) cases.

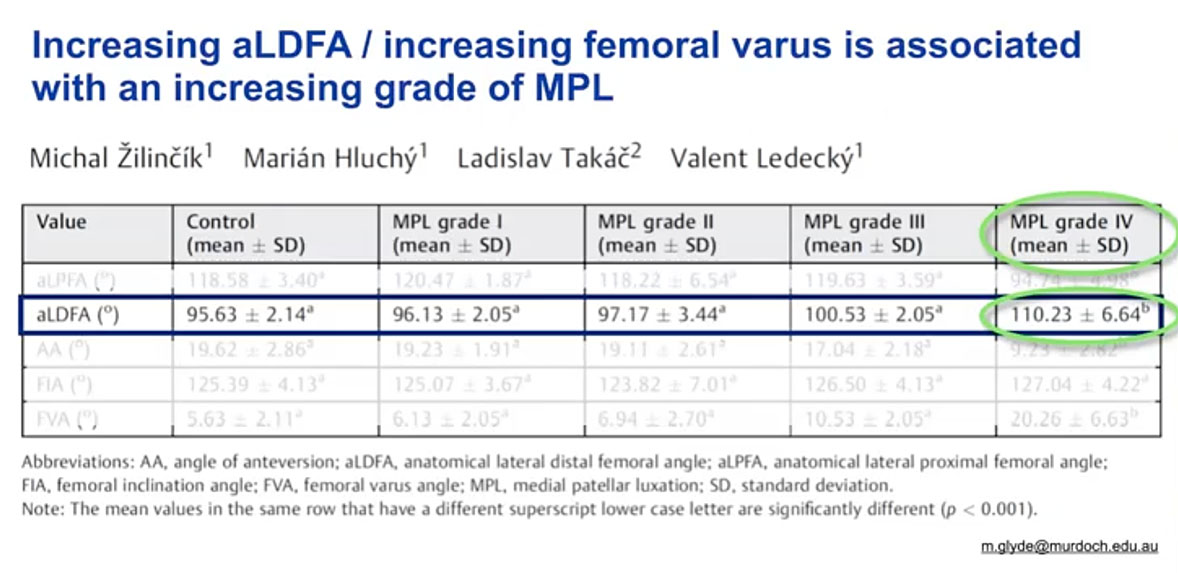

An increasing aLDFA is associated with an increasing grade of severity of MPL. This study correlating aLDFA with grade of luxation shows that most grade 4 MPL cases are associated with a marked increase in aLDFA. Here you can see the aLDFA by grades (Fig 3, below and 7:22).

As you can see, once you get up to the grade 4 MPLs, the mean aLDFA value is very high necessitating a corrective osteotomy, but there are some high-grade 3s that also will need correction. So as a general rule, we’re talking about grade 4 and high-grade 3 MPLs that will require a corrective femoral osteotomy.

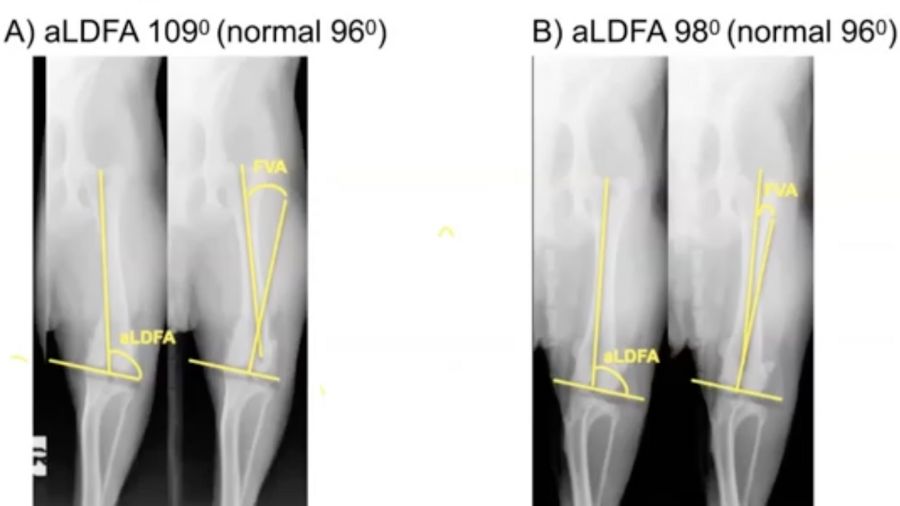

A word of caution, however. Have a look at the two cases in (Fig 4, 7:51). The image on the left has an aLDFA of 109, which is quite a big increase on the normal value of 96. The image on the right has an aLDFA of 98. You can probably already tell that these are actually the same dog and it's the radiographic positioning that is wrong – because you need to ensure that the femur is perpendicular to the beam and that the condyles bisect the fabellae.

In Figure 5 (8:37) is another example. Same dog, same leg, very similar position, but in the right-hand image there's slight rotation. The fabellae are not symmetrically bisected, and this shows a 7 positioning error. which would lead to the wrong decision on treatment. So correct positioning is critical when measuring aLDFA from radiographs. It's certainly much easier to measure the correct angle if you have access to CT because you can manipulate the image to get the bone in the right plane after acquisition of the scan, so positioning is less critical.

Once you’ve measured the aLDFA, what other considerations are there before deciding whether a standard 4 in 1 correction is likely to be effective, or whether a distal femoral osteotomy will also be required?

Firstly, the standing clinical exam is important (Fig 6, 9.28), because this determines the grade of severity of luxation and gives an indication of the offset in the frontal plane between the center of the trochlea groove and the tibial tuberosity. Remember that in a normal dog the tibial tuberosity should be positioned immediately distal to the center of the trochlea groove. The patella is a sesamoid bone in the quadriceps extensor mechanism. The quadriceps inserts on the tibial tuberosity through the patella tendon. So, if the tibial tuberosity is offset and not positioned immediately distal to the trochlea groove, the patella tendon creates a shear force that acts on the patella. Depending on the magnitude of the offset, the effect of this can range from abnormal tracking of the patella within the trochlea groove and consequent abnormal retropatellar cartilage pressure and wear, to intermittent luxation (grade 2 MPL), right through to persistent luxation (grade 3 or 4 MPL).

So, assessing the grade of severity of patella luxation and assessing the frontal plane offset in the standing animal gives an indication of the amount of correction in millimeters that will be necessary to resolve the luxation or resolve the abnormal patella tracking. There are no validated guidelines for dog sizes or breeds regarding what is the amount of frontal plane offset that can be corrected with a standard 4 in 1 surgery, and what offset would necessitate corrective osteotomies, but with experience you learn what's achievable in dogs of different sizes. As a rule of thumb, nearly all grade 2 and most grade 3 MPLs have a frontal plane offset that can be resolved with a standard 4 in 1 surgery. Conversely nearly all grade 4 and some more severe grade 3 MPLs will have such a significant frontal plane offset that a corrective osteotomy will be necessary.

There are some cases, typically high grade 3 MPLs, where despite the presence of significant femoral varus (aLDFA >104–106°) the amount of frontal plane offset is not particularly large and so by tibial tuberosity transposition (TTT) the tuberosity can be lateralized to be positioned immediately distal to the trochlea groove. In these cases however, despite resolving the frontal plane offset and aligning the trochlea groove and the tuberosity, the oblique angle of the trochlea groove due to the femoral varus means that the patella will track abnormally or obliquely through the trochlea. This leads to abnormal cartilage loading or abnormal retropatellar pressure and consequent ongoing cartilage wear, pain and perpetuation of osteoarthritis, despite resolving the luxation.

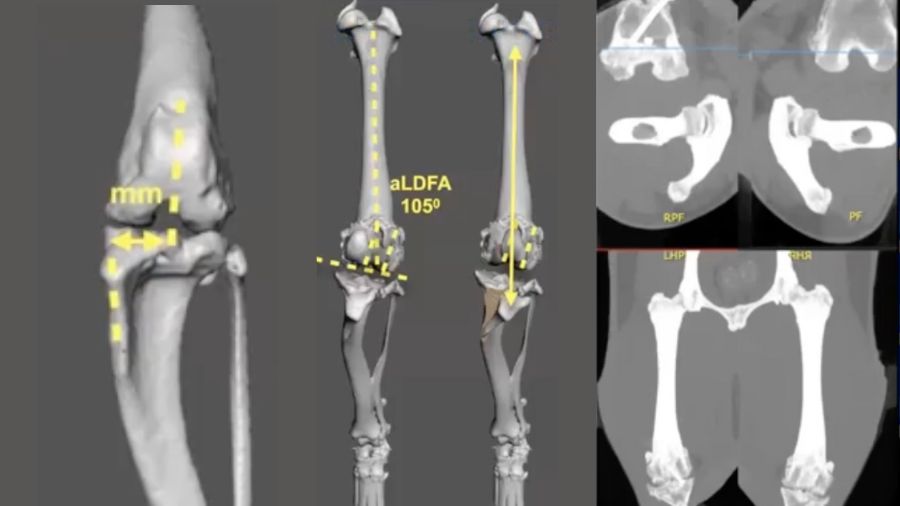

This is apparent in the CT renderings in Fig 7 (10:19) where a major translation of the tibial tuberosity has been simulated, resolving the frontal plane offset, but because of the unresolved significant femoral varus, the patella is tracking obliquely and quite abnormally through the trochlea. Even by forcing the patella to stay in place with a failed ridge replacement (Fig 8 10.54), you would still get abnormal tracking, erosion, and significant pain. An oblique trochlea creates abnormal patellar tracking and abnormal retropatellar pressures and is not a benign thing. So it is important to understand that managing more complex patella luxation cases is not just about keeping the patella from luxating.

With the tibia, it's less common to do a frontal plane corrective osteotomy than the femur, but again, it is all about measuring the angles, identifying the component deformities that are causing the luxation, and resolving the key deformities.

In the femur the frontal plane angles are referent to the anatomic axis of the femur. For the tibia, we use the mechanical axis, drawn from the center of the tibia proximally to the center of the tibia distally on a true craniocaudal radiograph or CT scan, and the proximal and distal joint reference lines. By convention the angulation of the frontal plane of the tibia is the mechanical Medial Proximal Tibial Angle (mMPTA), and the mechanical Medial Distal Tibial Angle (mMDTA), which are approximately 93° and 96° respectively. Most commonly MPL is associated with tibial valgus deformities with increased mMPTA.

Can this assessment of the grade of severity of luxation and the magnitude of the frontal plane offset be made in an anaesthetised dog? It is of course important to always repeat the orthopaedic examination when the animal is sedated or anaesthetised for imaging. However, it is necessary to recognise that because the quadriceps mechanism is a dynamic structure, both the grade of severity and the magnitude of frontal plane offset, may be different between the same dog depending on whether it is conscious with an actively loaded quadriceps mechanism or is unconscious with a passively loaded quadriceps mechanism.

Torsional or axial deformity, and the benefit of CT scans

A big frontal plane offset normally correlates with dogs that in addition to a significant femoral varus (the typical grade 4 MPL or severe grade 3 MPL with an aLDFA >104–106°) also have a significant torsional or axial deformity. Remember that the third anatomic plane is the axial, or bird’s eye view, which is parallel to the ground and divides the bone into the proximal and distal parts (Fig 9, 12:23). Torsional or axial deformities are difficult to assess with radiographs, and CT has certainly simplified this assessment.

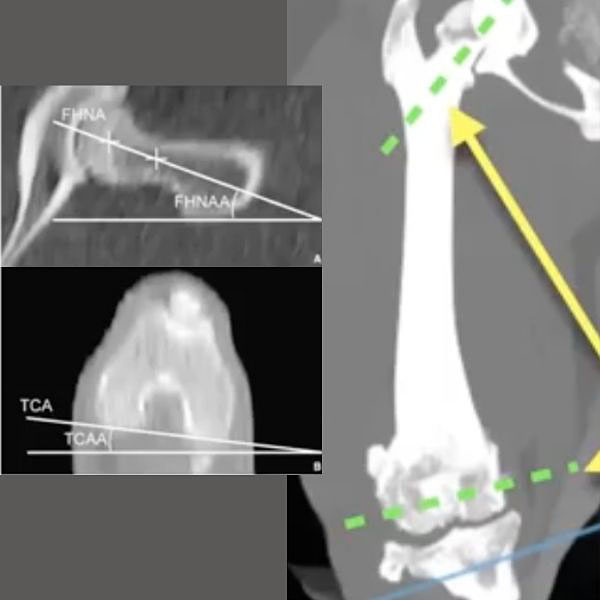

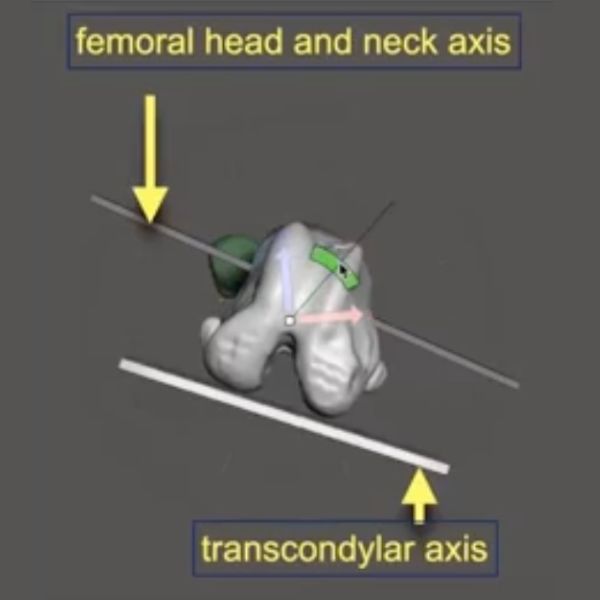

For the femur, the amount of torsion between the head and neck of the proximal femur and the condyles of the distal femur is called the femoral anteversion angle (FAA) and ranges between 16–31°. In Fig 10 (12:53), on the right is an axial plane view of the distal femur showing the condyle, and on the left an axial plane view of the proximal femur along the angle of inclination. The methodology for this has been previously published so we won’t go into detail in this article. Again, the Atlas of Clinical Goniometry and Radiographic Measurement of the Canine Pelvic Limb by Massimo Petazzoni and Gayle H Jaeger is an excellent reference source.

Anteversion is when the femoral head and neck points cranial to the frontal plane of the femur, and retroversion is when it points caudal to the frontal plane of the femur. Normoversion is when the femoral head and neck are at right angles to the sagittal plane. Anteversion has a positive angle and retroversion has a negative angle.

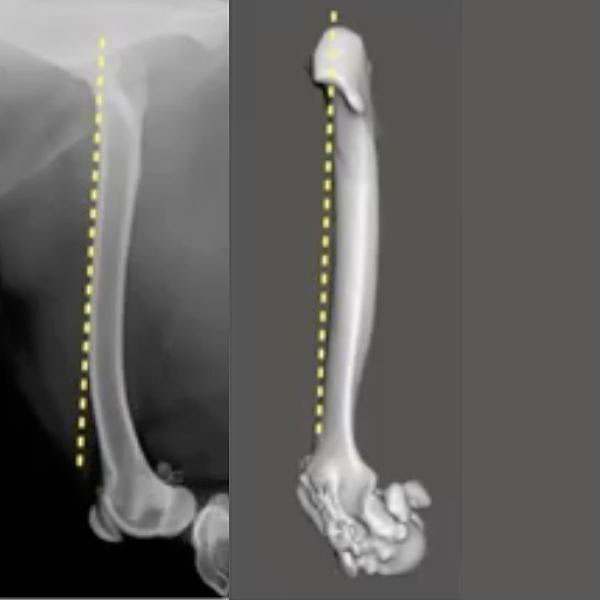

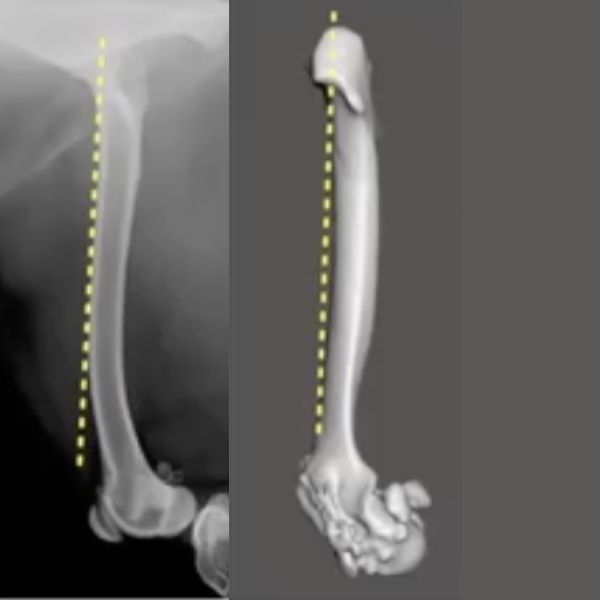

Why is this important? When we take a well-positioned, true lateral radiograph, you can get a visual impression of the anteversion angle. (Fig 11, 13:43) The image on the left is at the top end of normal, and as a rule of thumb, in a perfectly positioned lateral x-ray of the femur (whereby the femoral condyles are overlapping) about 50% of the femoral head would be cranial to the dotted yellow line that marks the cranial edge of the femur. On the right image there is no femoral head visible as it is obscured by the greater trochanter. The condyles in this image are superimposed so this confirms that the X-ray or in this case CT rendering is a true lateral. This apparent absence of any of the femoral head cranial to the line that marks the cranial edge of the femur in a well-positioned lateral radiograph, gives a strong indication that the femoral head and neck have a decreased angle of anteversion or are relatively retroverted. A decreased angle of anteversion or relative or absolute retroversion is associated with medial patella luxation as in the standing dog this externally torses or supinates the femoral condyles and trochlea groove away from the sagittal plane. This can create quite significant frontal plane offset and is strongly associated with MPL.

This concept of how a reduced angle of anteversion or relative retroversion of the femoral head and neck in the proximal femur creates external torsion of the distal femur and femoral condyles can be difficult to understand initially. The best way to understand this is to recognize that a normal acetabulum is retroverted by typically 15–25 (Fig 12, 14:51). If you think of the femoral head and neck “docking” into this retroverted or slightly caudally facing acetabulum, that means the femoral head and neck should have a corresponding cranially facing angle of anteversion.

So when we think of a decreased angle of anteversion / relative retroversion, we need to think of the femoral head and neck as being “docked” or relatively fixed with respect to its angulation into the acetabulum and so consider what's happening distally with the femoral condyles and trochlea groove. In Fig 13 (15.28), we’re creating retroversion, and you can see that with a fixed femoral head and neck, it externally torses or supinates the trochlear groove. So, a decreased angle of anteversion / relative retroversion creates this classic supination or external torsion of the trochlea groove. The lower the angle of anteversion / the more relatively retroverted the femoral head and neck are, the greater the frontal plane offset you will palpate between the center of the trochlea groove and the tibial tuberosity. Unsurprisingly the higher grades of severity of MPL are associated with correspondingly decreased magnitude of FAA (relative or absolute retroversion).

The first indication of significant torsional deformities therefore comes with the standing orthopaedic examination. High grades of MPL severity and/or a large magnitude of frontal plane offset between the trochlea groove and the tibial tuberosity should raise an index of suspicion that there may be a significant torsional or axial deformity of the femur +/- the tibia.

The second indication of concern for a significant torsional or axial deformity is as soon as we look at a perfectly positioned lateral radiograph (femoral condyles superimposed), or in this case a lateral CT rendering (Fig 14, 16:04). If you can't see 50% of the femoral head cranial to a line along the cranial edge of the femur, then you need to be suspicious that there is a significant component of femoral torsional deformity.

On the left image is an increased angle of anteversion, while the rendering on the right is a decreased angle of anteversion.

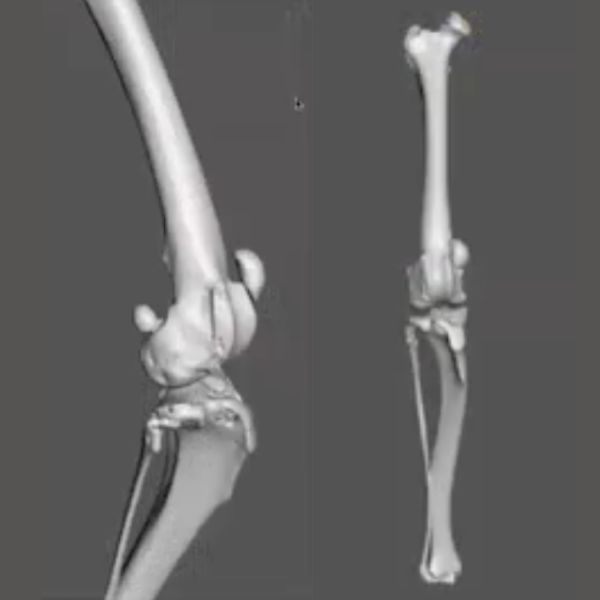

What about torsional or axial deformities of the tibia?

MPL is associated with supination or external torsion of the distal tibia. There are various described methods for measuring the angle of tibial torsion from radiographs or ideally a CT scan. Again, this methodology is outside the scope of this article, and we would refer you to other reference publications (Veterinary Surgery. 2021;353-364, Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound. Vol. 46, No. 3, 2005, pp 187-191).

The generally accepted method is to measure the offset between the caudal tibial condylar axis proximally and the cranial tibial axis distally to determine the magnitude of tibial torsion (Fig 15, 16:26). A normal distal tibia is internally torsed or pronated approximately five degrees relative to the proximal tibia. Supination or external torsion of the distal tibia creates corresponding abnormal pronation or internal rotation of the tibial tuberosity as expedience of ambulation has the toes and pes pointing roughly sagittal in the direction of movement.

Proximodistal position of the tibial tuberosity and patella: patella baja and patella alta

For this article, we will not consider sagittal plane deformities in detail. The key sagittal plane consideration for MPL relates to the relative proximodistal position of the tibial tuberosity (measured by the Z angle) and the relative proximodistal position of the patella in relation to the trochlea groove. Proximodistal position of the patella can be assessed in the frontal plane also however is most easily assessed in sagittal plane (mediolateral) imaging and is considered here.

Several publications have explored a ratio to determine an “absolute” measurement of the normal position of the patella as a ratio of the length of the patella tendon (Anatomica Veterinaria and some authors use the term “ligament” rather than tendon, however as it functions as a tendon by definition of having a sesamoid bone embedded in it for mechanical advantage and histologically it has the characteristics of a tendon more so than a ligament, we deliberately use the term “tendon”.) This ratio-based characterization of a patella as being too proximal (patella alta) or too distal (patella baja) works well in humans however, given the breed related conformational deformities in canines, particularly in chondrodystrophoid breeds, does not have as much decision-making relevance in veterinary orthopaedics.

What is more relevant with regard to small animal patella luxation is the concept of relative patella position, where the patella is positioned in relation to the trochlea groove throughout the full range of stifle joint flexion and extension. (Fig 16, 17:05). On full extension the patella is at its most proximal position in relation to the trochlea groove, while on full flexion the patella is at its most distal position. Validated measurements of normal relative positioning across a range of breeds are not available however as a rule of thumb in normal dogs no more than 1/3 of the patella would be proximal to the proximal end of the trochlea ridges on full extension and no more than 1/3 of the patella would be distal to the distal end / long digital extensor tendon on full flexion. The proximal end of the medial trochlea ridge ends slightly more distally than that of the lateral ridge.

Surgical correction of the proximodistal position of the patella should not be made based on an absolute ratio measurement alone. It is more reliable to base decision-making on the relative position of the patella within the trochlea groove through the range of motion. This should be assessed on palpation and on range of motion imaging studies.

Significant patella alta is more commonly though not exclusively associated with medial patella luxation. Significant patella baja is often associated with lateral patella luxation but again not exclusively so.

Corrections of relative proximodistal positioning of the patella and trochlea groove and proximodistal position of the tibial tuberosity should not be made prior to skeletal maturity.

To summarize, this article provides an overview of the anatomic planes and angles to consider when assessing a dog for management of more complex cases of patella luxation that may require corrective osteotomy(ies) in addition to standard surgery. Assessment and surgical planning require a thorough and informed orthopaedic examination in addition to correctly positioned X-rays or CT scans. CT scans expedite and simplify the acquisition of the images necessary to assess the deformities in the frontal, axial and sagittal planes.

The grade of severity and the magnitude of the frontal plane offset between the trochlea groove and the tibial tuberosity as assessed during a standing orthopaedic examination provide a key indication of the likely extent of surgery necessary to resolve the problem.

Most cases of medial patella luxation comprise grade 2 and 3 grades of severity. These can most commonly be managed by standard 4 in 1 corrective surgery including trochleoplasty, tibial tuberosity transposition, lateral fascial imbrication and medial desmotomy. Grade 4 cases and some more severe grade 3 cases have significant anatomic deformities that require correction through corrective osteotomy(ies). Failure to recognize and effectively correct these component deformities greatly increases the risk of surgical failure and reluxation.

Distal femoral ostectomy to correct femoral varus and excessive femoral supination is the most common corrective osteotomy in addition to standard 4 in 1 surgery in the management of more complex cases of patella luxation.

This article was inspired by the recent AO VET webinar Corrective Osteotomies for Stifle Joint Problems: Tips, Tricks and Considerations in Planning and Execution with Lucas Beierer, Mark Glyde, and Kevin Parsons.

About the authors

Lucas Beierer graduated from the University of Queensland before becoming a Diplomat of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons in 2015. He spent several years working in north-west England prior to returning to Brisbane. Lucas is now director of Queensland Veterinary Specialists, and he is active faculty of AO VET and serves on the AO VET Technical Commission. He's an experienced educator and loves to share technical aspects of surgery which improves safety and efficacy.

Professor Mark Glyde leads Murdoch University's orthopedic referral service. He's an Australian, European and RCVS recognised specialist surgeon and an ECVS diplomat. He's an internationally recognized and awarded teacher teaching globally in the field of veterinary orthopedics. He chairs the AO VET Education Commission and is a member of the AOVET International Board

References and further reading:

- Atlas of clinic Goniometry and Radiographic Measurements of the Canine Pelvic Limb. (Massimo Petazzoni. Gayle H Jaeger, 2nd Edition, Previcon)

- A three-dimensional computed tomographic volume rendering methodology to measure the tibial torsion angle in dogs. Veterinary Surgery. 2021; 353-364

- Computed tomographic determination of tibial torsion in the dog. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound. Vol. 46, No. 3, 2005, pp 187-191

You might also be interested in:

Lameness in dogs: diagnosis and decision-making

The 6-week AO VET online competency-based course focuses on enhancing decision-making skills and improving outcomes in canine surgery.

AO VET courses and events

Explore our upcoming courses, webinars, and online events in your region.

AO VET Guest Blog

Read more guest articles from the AO VET or submit your own posts to promote your work and passions.

How to get involved in AO VET

Becoming an AO VET friend could lead to a life-long partnership, from finding your best learning pathway to becoming an active officer.