Management strategies for pelvic discontinuity

Preview

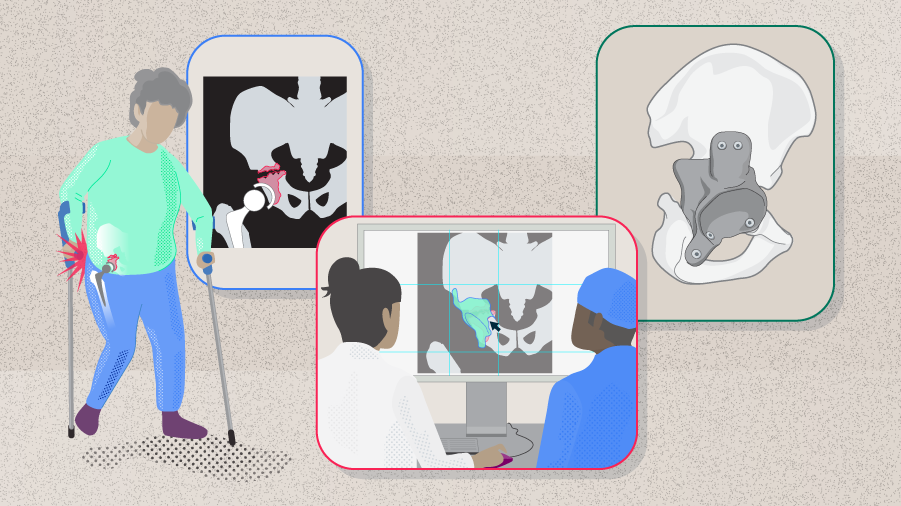

Pelvic discontinuity (PD), also called pelvic disassociation or acetabular disassociation, is an uncommon condition most frequently encountered during revision total hip arthroplasty (rTHA). The management of pelvic discontinuity involves acetabular reconstruction to restore the center of rotation and acetabular integrity. Depending on the degree of bone loss, this can be demanding and challenging even for experienced revision arthroplasty surgeons. In this article, Theofilos Karachalios, Chairman of the Orthopaedic Department, University General Hospital of Larissa at the University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece, will share with us some of the most important aspects in treating PDs.

Theofilos Karachalios

University General Hospital of Larissa at the University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece

Pelvic discontinuity

Pelvic discontinuity is the loss of structural continuity between the superior and the inferior part of the pelvis. It progresses through the anterior and posterior columns of the acetabulum so that the superior aspect of the pelvis is completely dissociated from the inferior structures [1–4]. It can be acute or chronic, with chronic PD being much more common [1, 4]. Acute PD is usually caused by trauma such as a fresh periprosthetic fracture arising during the impaction of an uncemented acetabular component or during the removal of an acetabular component in rTHA. An acute PD is more likely to have minimum gapping between the superior and inferior pelvis, thus bone apposition may be less problematic [1, 5]. Chronic PD involves progressively increasing bone loss around loose acetabular components and may involve a large amount of fibrous tissue between the superior and inferior hemipelves, with the bone itself being sclerotic and nonvascularized. Due to the difference in biology and mechanics, the healing potentials are different between the two types of PD [1–4]. Although PD is relatively uncommon, its incidence has been projected to increase due to the increasing number of primary and rTHAs [6].

Classification

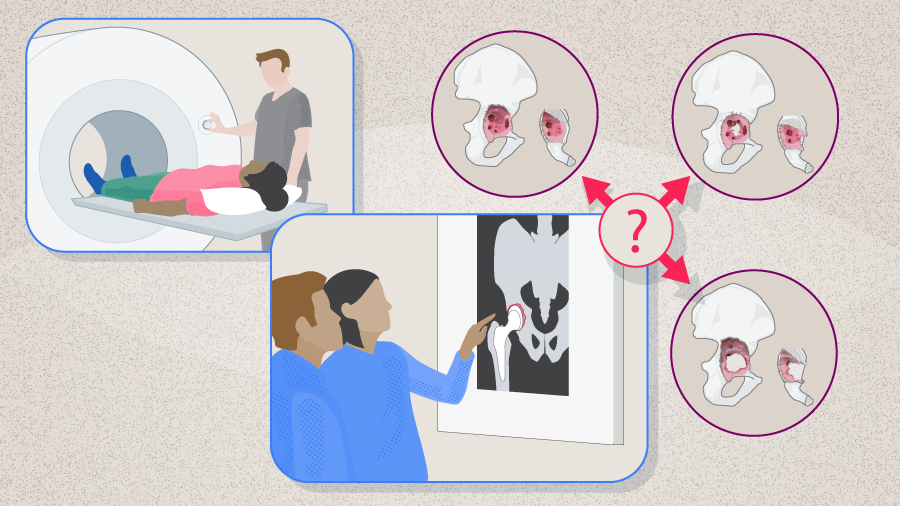

Acetabular deficiencies are commonly classified according to either the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) classification scheme or the Paprosky system (See Part 1 of this series for more details). According to the AAOS classification, PDs are type IV deficiencies [7]. Berry et al [2] further divided the type IV deficiencies into type IVa (PD with cavitary bone loss), type IVb (PD with segmental bone loss), and type IVc (PD in previously irradiated pelvis with or without bone defects). In the commonly used Paprosky Classification, PD is often associated with type IIIB defects but can also be seen in type IIC and IIIA bone defects [8].

Read the full article with your AO login

- Pelvic discontinuity

- Classification

- Diagnosis

- Did you know?

- Preoperative assessment

- Intraoperative assessment

- Postoperative assessment

- Acute pelvic discontinuity

- Chronic pelvic discontinuity

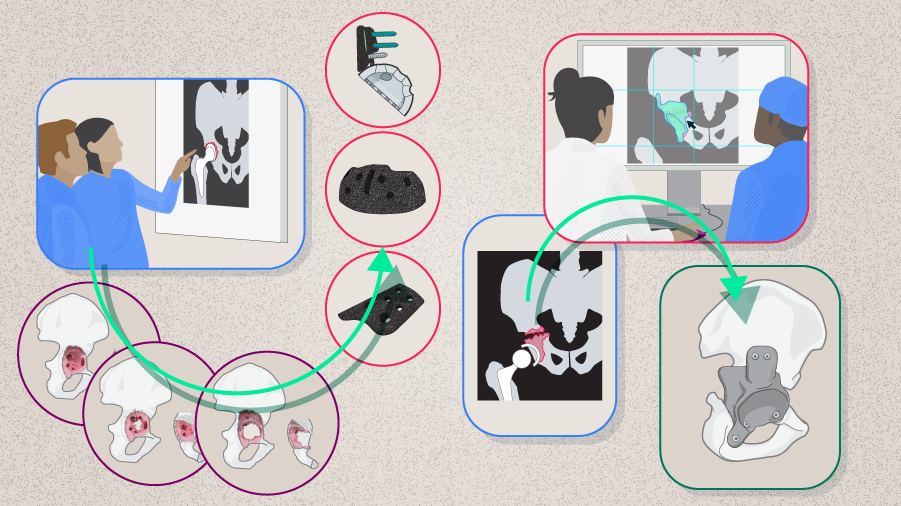

- Cages and rings with graft

- Internal fixation with acetabular reconstruction

- Acetabular distraction with cementless acetabular cup

- Tantalum cementless acetabular cups with augments

- Cup and cage construct

- Triflange and custom-made acetabular implants

- Asking the expert

- Conclusion

AO Recon resources

Contributing experts

This series of articles was created with the support of the following specialists (in alphabetical order):

Theofilos Karachalios

University General Hospital of Larissa at the University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece

Thomas Kostakos

Henry Dunant Medical Center, Athens, Greece

George A Macheras

Henry Dunant Medical Center, Athens, Greece

The authors thank Maio Chen, medical writer at AO Innovation Translation Center, Switzerland, for contributing to the writing and editing of the articles.

References

- Babis GC, Nikolaou VS. Pelvic discontinuity: a challenge to overcome. EFORT Open Rev. 2021 Jun;6(6):459–471.

- Berry DJ, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD, Cabanela ME. Pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999 Dec;81(12):1692–1702.

- Hasenauer MD, Paprosky WG, Sheth NP. Treatment options for chronic pelvic discontinuity. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018 Jan-Mar;9(1):58–62.

- Schwarzkopf R, Ihn HE, Ries MD. Pelvic discontinuity: modern techniques and outcomes for treating pelvic disassociation. Hip Int. 2015 Jul-Aug;25(4):368–374.

- Abdel MP, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Pelvic Discontinuity Associated With Total Hip Arthroplasty: Evaluation and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017 May;25(5):330–338.

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Apr;89(4):780–785.

- D'Antonio JA, Capello WN, Borden LS, et al. Classification and management of acetabular abnormalities in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989 Jun(243):126–137.

- Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty. 1994 Feb;9(1):33–44.

- Sculco PK, Wright T, Malahias MA, et al. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Acetabular Bone Loss in Revision Hip Arthroplasty: An International Consensus Symposium. Hss j. 2022 Feb;18(1):8–41.

- Amanatullah D, Dennis D, Oltra EG, et al. Hip and Knee Section, Diagnosis, Definitions: Proceedings of International Consensus on Orthopedic Infections. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Feb;34(2S):S329–S337.

- Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Acetabular revision using a trabecular metal acetabular component for severe acetabular bone loss associated with a pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty. 2006 Sep;21(6 Suppl 2):87–90.

- Sporer SM, O'Rourke M, Paprosky WG. The treatment of pelvic discontinuity during acetabular revision. J Arthroplasty. 2005 Jun;20(4 Suppl 2):79–84.

- Giori NJ, Sidky AO. Lateral and high-angle oblique radiographs of the pelvis aid in diagnosing pelvic discontinuity after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011 Jan;26(1):110–112.

- Puri L, Wixson RL, Stern SH, et al. Use of helical computed tomography for the assessment of acetabular osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002 Apr;84(4):609–614.

- Rogers BA, Whittingham-Jones PM, Mitchell PA, et al. The reconstruction of periprosthetic pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty. 2012 Sep;27(8):1499–1506 e1491.

- Wellenberg RHH, Hakvoort ET, Slump CH, et al. Metal artifact reduction techniques in musculoskeletal CT-imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2018 Oct;107:60–69.

- Desai G, Ries MD. Early postoperative acetabular discontinuity after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011 Dec;26(8):1570 e1517–1579.

- Garbuz D, Morsi E, Gross AE. Revision of the acetabular component of a total hip arthroplasty with a massive structural allograft. Study with a minimum five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996 May;78(5):693–697.

- Sporer SM, Bottros JJ, Hulst JB, et al. Acetabular distraction: an alternative for severe defects with chronic pelvic discontinuity? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Nov;470(11):3156–3163.

- Abolghasemian M, Tangsaraporn S, Drexler M, et al. The challenge of pelvic discontinuity: cup-cage reconstruction does better than conventional cages in mid-term. Bone Joint J. 2014 Feb;96-B(2):195–200.

- Paprosky W, Sporer S, O'Rourke MR. The treatment of pelvic discontinuity with acetabular cages. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006 Dec;453:183–187.

- Regis D, Sandri A, Bonetti I, et al. A minimum of 10-year follow-up of the Burch-Schneider cage and bulk allografts for the revision of pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty. 2012 Jun;27(6):1057–1063 e1051.

- Villanueva M, Rios-Luna A, Pereiro De Lamo J, et al. A review of the treatment of pelvic discontinuity. HSS J. 2008 Sep;4(2):128–137.

- Brown NM, Hellman M, Haughom BH, et al. Acetabular distraction: an alternative approach to pelvic discontinuity in failed total hip replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014 Nov;96-B(11 Supple A):73–77.

- Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, et al. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999 Sep;81(5):907–914.

- Batuyong ED, Brock HS, Thiruvengadam N, et al. Outcome of porous tantalum acetabular components for Paprosky type 3 and 4 acetabular defects. J Arthroplasty. 2014 Jun;29(6):1318–1322.

- Jenkins DR, Odland AN, Sierra RJ, et al. Minimum Five-Year Outcomes with Porous Tantalum Acetabular Cup and Augment Construct in Complex Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 May 17;99(10):e49.

- Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG. Modular acetabular augments: composite void fillers. Orthopedics. 2005 Sep;28(9):971–972.

- Sculco PK, Ledford CK, Hanssen AD, et al. The Evolution of the Cup-Cage Technique for Major Acetabular Defects: Full and Half Cup-Cage Reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Jul 5;99(13):1104–1110.

- Amenabar T, Rahman WA, Hetaimish BM, et al. Promising Mid-term Results With a Cup-cage Construct for Large Acetabular Defects and Pelvic Discontinuity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016 Feb;474(2):408–414.

- Konan S, Duncan CP, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. The cup-cage reconstruction for pelvic discontinuity has encouraging patient satisfaction and functional outcome at median 6-year follow-up. Hip Int. 2017 Sep 19;27(5):509–513.

- Taunton MJ, Fehring TK, Edwards P, et al. Pelvic discontinuity treated with custom triflange component: a reliable option. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Feb;470(2):428-434.

- DeBoer DK, Christie MJ, Brinson MF, Morrison JC. Revision total hip arthroplasty for pelvic discontinuity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Apr;89(4):835–840.