Common modifiable risk factors in total joint arthroplasty: a 2021 update—diabetes

Preview

The role of glycemic control before total joint arthroplasty (TJA) has received intense scrutiny in the past 20 years. Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), especially those with inadequate glycemic control, have been associated with increased risk for both joint-related and systemic adverse outcomes following TJA [1–3]. This observation, however, has been disputed by others, who showed that diabetic patients did not have increased odds of complications [4, 5]. What is the current evidence for supporting perioperative glycemic control? What is a proper glycemic control? In this article, Matthew P Abdel, Andrew A. and Mary S. Sugg Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Chair of Division of Orthopedic Surgery Research at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, US, reviews the current evidence of what tools are available for glycemic control at the chronic, subacute, and acute levels in managing (potential) TJA patients.

Matthew P Abdel

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, United States

Population-based studies demonstrating the influence of uncontrolled hyperglycemia

The incidence of diabetes is increasing. Current literature estimates that 8.5–20.7% of patients undergoing TJA in the US were diabetic; in a local population, the percentage can be even higher [3, 6].

The effect of diabetes or uncontrolled hyperglycemia on health and outcomes of medical treatments has been well established. Quoting a publication showing intensive insulin therapy in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction led to better long-term outcomes, Van den Berghe et al [7] published in 2001 a randomized controlled study on 1,548 critically ill patients and demonstrated that an intensive insulin therapy resulted in, for example, lower mortality, shorter stay in the intensive care unit, lower rate of bloodstream infection, and lower rate of acute renal failure.

Does diabetes or uncontrolled hyperglycemia have similar influence on the outcomes after TJA? In the past two decades, many have attempted to answer this question.

In their 2008 publication, Bolognesi et al [8] demonstrated that diabetic patients had substantially increased odds of pneumonia, stroke, and transfusion after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Using the data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the study included 751,340 primary or revision THA or TKA patients, and the results can be considered generally applicable to the American population. In their subsequent publication, Marchant et al [2] used the data from the same database to further examine over one million patients to evaluate the effect of glycemic control. In their investigation, patients were divided into three cohorts: 3,937 patients with uncontrolled DM, 105,485 patients with controlled DM, and 920,555 patients without DM. After adjusting for a long list of potentially confounding factors such as sex, age, race, comorbidity, household income, and surgeon volume, the authors showed that patients with uncontrolled DM had significantly higher risk (than patients without DM) of cerebrovascular accidents, infections, and mortality, the list of adverse results goes on.

These two studies provided valuable information, but they have limitations that are typically associated with retrospective studies, ie, the uncertainty of the data quality and the unavailability of crucial information. For example, in the Marchant et al [2] study, uncontrolled factors such as different perioperative screening protocols may have skewed the patient population, causing unexpected results such as higher odds of experiencing a postoperative myocardial infarction in the nondiabetic than in the diabetic patients. Other limitations include, for example, relying on the database coding (performed in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases codes, ninth revision, ICD-9) that was not directly validated against the clinical data and using subjective criteria to determine the glycemic control status for the grouping of cohorts [2, 4, 9].

Read the full article with your AO login

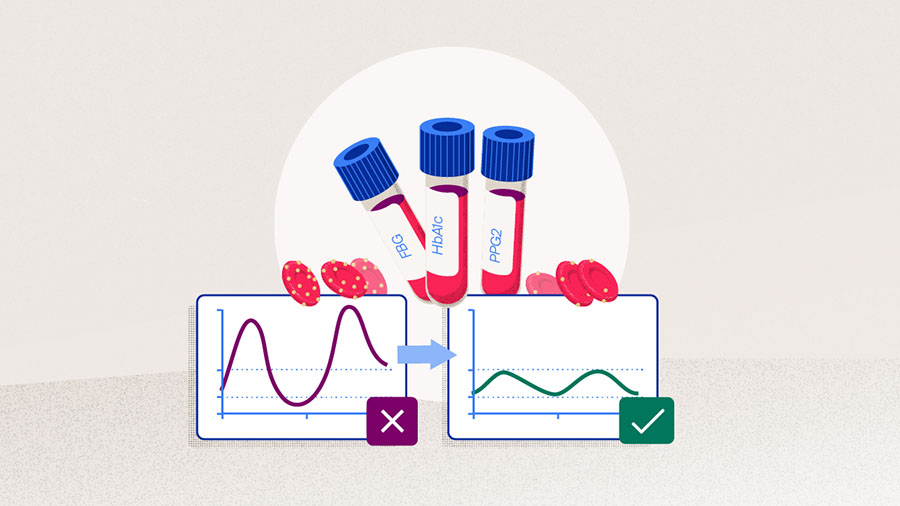

- Putting numbers to glycemic control

- In the name of better outcomes after arthroplasty

- Is there a better marker for glycemic control than HbA1c?

- Consistency may be more important

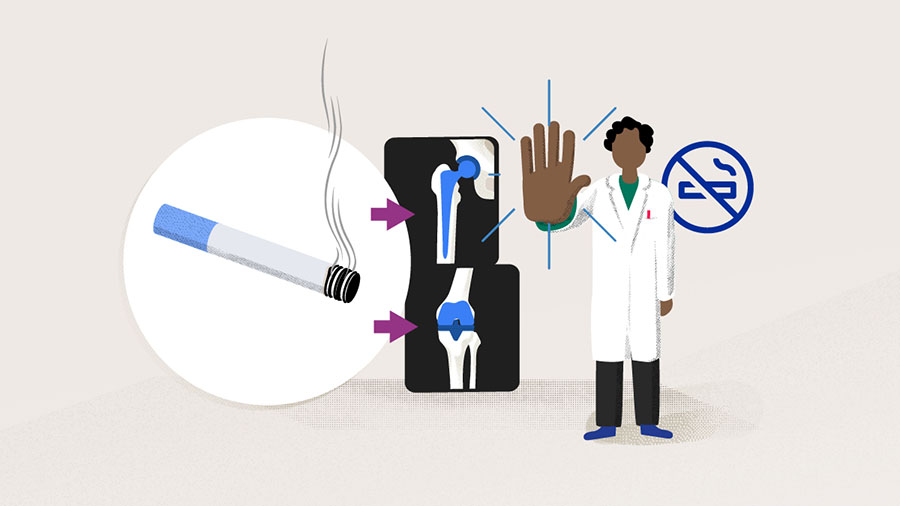

- Glycemic control should be part of a multimodal optimization

- Conclusion

Additional AO resources

Access videos, tools, and other assets.

- Videos

- AOF books in Thieme store

- Upcoming events: AO Recon Course finder

Contributing experts

This series of articles was created with the support of the following specialists (in alphabetical order):

Matthew P Abdel

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, United States

Steven MacDonald

University of Western Ontario

London, Canada

Michael A Mont

Rubin Institute for Advanced Orthopedics

Baltimore, United States

This article was compiled by Maio Chen, Senior Project Manager Medical Writing, AO Foundation, Switzerland.

References

- Maradit Kremers H, Schleck CD, Lewallen EA, et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperglycemia and the Risk of Aseptic Loosening in Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017 2017/09/01/;32(9, Supplement):S251–S253.

- Marchant MH, Jr., Viens NA, Cook C, et al. The impact of glycemic control and diabetes mellitus on perioperative outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jul;91(7):1621–1629.

- Shohat N, Goswami K, Tarabichi M, et al. All Patients Should Be Screened for Diabetes Before Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018 Jul;33(7):2057–2061.

- Adams AL, Paxton EW, Wang JQ, et al. Surgical outcomes of total knee replacement according to diabetes status and glycemic control, 2001 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Mar 20;95(6):481–487.

- Ojemolon PE, Shaka H, Edigin E, et al. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Outcomes of Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis Who Underwent Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Cureus. 2020 Jun 29;12(6):e8902.

- Giori NJ, Ellerbe LS, Bowe T, et al. Many diabetic total joint arthroplasty candidates are unable to achieve a preoperative hemoglobin A1c goal of 7% or less. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Mar 19;96(6):500–504.

- van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1359–1367.

- Bolognesi MP, Marchant MH, Jr., Viens NA, et al. The impact of diabetes on perioperative patient outcomes after total hip and total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008 Sep;23(6 Suppl 1):92–98.

- George J, Piuzzi NS, Jawad MM, et al. Reliability of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Codes to Detect Morbid Obesity in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018 Sep;33(9):2770–2773.

- Association AD. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Supplement 1):S73–S84.

- Shohat N, Tarabichi M, Tischler EH, et al. Serum Fructosamine: A Simple and Inexpensive Test for Assessing Preoperative Glycemic Control. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Nov 15;99(22):1900–1907.

- Jämsen E, Nevalainen P, Kalliovalkama J, et al. Preoperative hyperglycemia predicts infected total knee replacement. Eur J Intern Med. 2010 Jun;21(3):196–201.

- Iorio R, Williams KM, Marcantonio AJ, et al. Diabetes mellitus, hemoglobin A1C, and the incidence of total joint arthroplasty infection. J Arthroplasty. 2012 May;27(5):726–729.e721.

- Harris AH, Bowe TR, Gupta S, et al. Hemoglobin A1C as a marker for surgical risk in diabetic patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013 Sep;28(8 Suppl):25–29.

- Han HS, Kang SB. Relations between long-term glycemic control and postoperative wound and infectious complications after total knee arthroplasty in type 2 diabetics. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013 Jun;5(2):118–123.

- Stryker LS, Abdel MP, Morrey ME, et al. Elevated postoperative blood glucose and preoperative hemoglobin A1C are associated with increased wound complications following total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 May 1;95(9):808–814, s801–802.

- Hwang JS, Kim SJ, Bamne AB, et al. Do glycemic markers predict occurrence of complications after total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 May;473(5):1726–1731.

- Chrastil J, Anderson MB, Stevens V, et al. Is Hemoglobin A1c or Perioperative Hyperglycemia Predictive of Periprosthetic Joint Infection or Death Following Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015 Jul;30(7):1197–1202.

- Cancienne JM, Werner BC, Browne JA. Is There a Threshold Value of Hemoglobin A1c That Predicts Risk of Infection Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2017 Sep;32(9s):S236–S240.

- Citak M, Toussaint B, Abdelaziz H, et al. Elevated HbA1c is not a risk factor for wound complications following total joint arthroplasty: a prospective study. Hip Int. 2020 Sep;30(1_suppl):19–25.

- Shohat N, Restrepo C, Allierezaie A, et al. Increased Postoperative Glucose Variability Is Associated with Adverse Outcomes Following Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018 Jul 5;100(13):1110–1117.

- Shohat N, Tarabichi M, Tan TL, et al. 2019 John Insall Award: Fructosamine is a better glycaemic marker compared with glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) in predicting adverse outcomes following total knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Bone Joint J. 2019 Jul;101-b(7_Supple_C):3–9.

- Jämsen E, Nevalainen PI, Eskelinen A, et al. Risk factors for perioperative hyperglycemia in primary hip and knee replacements. Acta Orthop. 2015 Apr;86(2):175–182.