Evaluation and treatment of extension and recurvatum instability

Preview

Instability after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) was introduced in Part 1 of this series. Two different and relatively uncommon forms of instability are extension instability and genu recurvatum. Hyperextension and recurvatum describe the same type of deformity, though for practical terms extension instability refers mostly to the result of the surgical technique used during the primary TKA (sometimes also coined as ‘instability due to bone resection’), whereas genu recurvatum describes the preexisting hyperextension. This preexisting hyperextension is usually associated with neuromuscular disease, such as poliomyelitis, or can occur in patients with a valgus deformity and a tight Iliotibial band, or in cases of cruciate and collateral ligament laxity, such as in rheumatoid arthritis [1]. A thorough understanding of the etiology of the instability is crucial to determine the correct course of treatment and the choice of implant used during revision TKA. In this article, Beatriz Montoya-Ortiz from the Clinical Care Center for Joint Replacement at Clínica El Rosario in Medellín, Colombia shares her clinical experience with us and takes us through the differences between extension instability and genu recurvatum, how to evaluate the patient, and considerations for treatment.

Beatriz Montoya-Ortiz

Clínica El Rosario

Medellín, Colombia

Extension instability

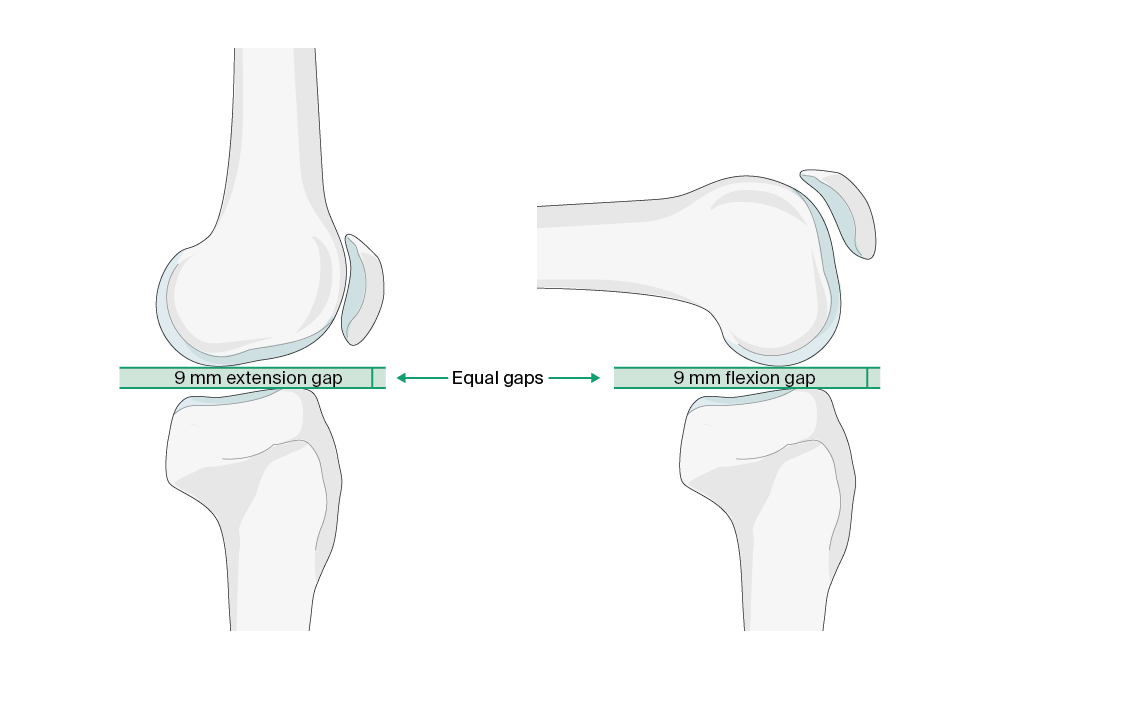

Extension instability can be described in patients who have a knee which is well balanced in flexion but loose in extension, usually with an elevation of the joint line [2]. It can be subclassified into the two types symmetric or asymmetric instability, with the latter being more common. Extension instability can be characterized by the shape of the extension gap, with a rectangular gap associated with symmetric, and a trapezoidal gap with asymmetric extension instability [3]. As Beatriz Montoya notes, the space between the transverse cut of the distal femur and the transverse proximal tibial cut (the extension gap) should be equivalent to the space between the posterior femur and the transverse proximal cut (the flexion gap) for the ligaments to be balanced (Figure 1). However, when preparing for the bone resection, if the alignment of the cutting guide changes or if an underlying angular deformity is not corrected, it changes the plane of resection, thus creating a mismatch between the gaps leading to instability.

Symmetric instability

In the case of symmetric extension instability, there has usually been excessive distal femoral or proximal tibial resection, and thus the extension gap cannot be appropriately filled by the components [4]. Excessive proximal tibial resection affects both extension and flexion gaps and can be managed typically using a thicker polyethylene insert that will fill the space equally in flexion and extension [3]. However, this is not appropriate when there is excessive distal femoral resection, because in this case the extension gap is primarily affected leaving the flexion gap unchanged, and a thicker tibial insert would raise the joint line and cause flexion gap tightness limiting deep flexion [1, 3].

Read the full article with your AO login

- Extension instability

- Symmetric instability

- Asymmetric instability

- Tips and tricks

- Hyperextension after total knee arthroplasty can impact quality of life

- Genu recurvatum

- Treatment choices in genu recurvatum

- Approaching the clinical examination in patients with suspected instability

- Conclusion

Additional AO resources

Access videos, tools, and other assets.

- Videos

- Upcoming events: AO Recon Course finder

- Surgery Reference: Periprosthetic Fractures—Unified Classification System for Periprosthetic Fractures (UCPF)

Contributing experts

Dario E Garin

Hospital Ángeles

Tijuana, Mexico

Beatriz Montoya-Ortiz

Clínica El Rosario

Medellín, Colombia

Sam Oussedik

AO Recon Joint Preservation Knee Curriculum Taskforce

University College Hospital London

London, UK

This issue was written by Lyndsey Kostadinov, AO Innovation Translation Center, Clinical Science, Switzerland.

References

- Parratte S, Pagnano MW. Instability after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):184–194.

- Al-Jabri T, Brivio A, Maffulli N, et al. Management of instability after primary total knee arthroplasty: an evidence-based review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):729.

- Cottino U, Sculco PK, Sierra RJ, et al. Instability After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(2):311–316.

- Abdel MP, Haas SB. The unstable knee: wobble and buckle. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(11 Supple A): 112–114.

- Petrie JR, Haidukewych GJ. Instability in total knee arthroplasty: assessment and solutions. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-b(1 Suppl A): 116–119.

- Miralles-Muñoz FA, Pineda-Salazar M, Rubio-Morales M, et al. Similar outcomes of constrained condylar knee and rotating hinge prosthesis in revision surgery for extension instability after primary total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(8):103265.

- Insall JN, Binazzi R, Soudry M, et al. Total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985(192):13–22.

- Nikolopoulos D, Michos I, Safos G, et al. Current surgical strategies for total arthroplasty in valgus knee. World J Orthop. 2015;6(6): 469–482.

- Nisar S, Palan J, Rivière C, et al. Kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(7): 380–390.

- Rivière C, Harman C, Boughton O, et al. The Kinematic Alignment Technique for Total Knee Arthroplasty. In: Rivière C, Vendittoli PA, eds. Personalized Hip and Knee Joint Replacement. Cham: Springer; 2020:175–195.

- Siddiqui MM, Yeo SJ, Sivaiah P, et al. Function and quality of life in patients with recurvatum deformity after primary total knee arthroplasty: a review of our joint registry. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1106–1110.

- Mhaskar VA, Maheshwari J. Total Knee Arthroplasty in Genu Recurvatum in Knee Arthroplasty. New and Future Directions. 2022:249–254.

- Meding JB, Keating EM, Ritter MA, et al. Genu recurvatum in total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003(416): 64–67.

- Pomeroy E, Fenelon C, Murphy EP, et al. A Systematic Review of Total Knee Arthroplasty in Neurologic Conditions: Survivorship, Complications, and Surgical Considerations. J Arthroplasty. 2020; 35(11):3383–3392.

- Seo SS, Kim CW, Lee CR, et al. Outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in degenerative osteoarthritic knee with genu recurvatum. Knee. 2018;25(1):167–176.

- Mesnard G, Batailler C, Fary C, et al. Posterior-Stabilized TKA in Patients With Severe Genu Recurvatum Achieves Good Clinical and Radiological Results at 5-year Minimum Follow-Up: A Case-Controlled Study. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(9):3154–3160.

- Digennaro V, Manzetti M, Bulzacki Bogucki BD, et al. Total knee replacements using rotating hinge implants in polio patients: clinical and functional outcomes. Musculoskeletal Surg. 2022.

- Prasad A, Donovan R, Ramachandran M. et al. Outcome of total knee arthroplasty in patients with poliomyelitis: A systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(6):358–362.

- Erceg M, Rakić M. Genu recurvatum as a complication after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Clin Croat. 2012;51(2):265–268.

- Mortazavi SMJ, Razzaghof M, Noori A, et al. Late-Onset De Novo Genu Recurvatum after Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Potential Indication for Isolated Polyethylene Exchange. Arthroplasty Today. 2020;6(3):492–495.

- McNabb DC, Kim RH, Springer BD. Instability after total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(2):97–104.